Painting the Queen (and her prime ministers)

- Published

Reproduced by kind permission of the Pannett family and the Chartered Insurance Institute

The artist Juliet Pannett painted many of the greatest figures of the 20th Century, including prime ministers, composers, servicemen and royals. Her son Denis talks about her fondest memories.

Each year the Queen has to sit through a couple of hours of comedy, music and light entertainment.

After the Royal Variety Show she has met and shaken the hands of some of the greats: Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Junior, Sacha Distel, Tommy Cooper, Sir Bruce Forsyth, Jimmy Tarbuck.

But away from the formality of the red carpet Her Majesty likes to tell the odd humorous anecdote or two herself.

In the late 1980s, the acclaimed artist Juliet Pannett was commissioned to produce a portrait for the Chartered Insurance Institute, after completing drawings of Prince Andrew and Prince Edward.

She and her son Denis, another painter, external, arrived at Buckingham Palace with a sense of trepidation.

'Relaxed'

Denis said: "We thought it would be very formal. I helped mother get the room ready for the portrait. I sat in the chair the Queen was going to sit in, so we could make sure the positioning and light were good.

"Then, at 11 o'clock, the door opened. A footman arrived. We had been told not to dress up, but the Queen arrived in the most beautiful silver evening dress. We were introduced and everybody except the Queen left and we were alone with her."

The Pannetts had expected a sombre few hours, but the Queen ensured the experience was anything but staid.

Denis Pannett posed as the Queen so his mother could get the lighting and position right

"It was really good fun," said Denis, who lives in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire. "The Queen chatted non-stop. She was amazing, with lots of stories. She was great fun.

"In one of her stories, she told us she had been at Sandringham one day. They were having tea when they ran out of cake. So, the Queen said she had gone gone down to the local shop to buy some, wearing a headscarf.

"As she came out of the shop, an elderly lady said 'Good heavens, you look just like the Queen.' She replied 'How reassuring' and just kept walking. It was a wonderful tale."

The easygoing encounter suited his mother: "She never wanted her subjects to stop talking, as it made them more relaxed and easier to capture."

The next time they visited the palace, the Pannetts were allowed to get to the first-floor Yellow Drawing Room unescorted.

"It was generally very informal. We took our time to get there, as there was so much to see. We spent a long time looking at the lovely portraits along the stairs and the corridor."

The Queen was delighted with the portrait by Mrs Pannett. It was the pinnacle of the career of the artist, who died in 2005, aged 94, but there were many highs.

Among Mrs Pannett's subjects were Field-Marshal Montgomery of Alamein, film director Jean Cocteau, runner Chris Chataway, jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong and conductor-composer Leonard Bernstein.

At the final Buckingham Palace sitting, Mrs Pannett presented the Queen with a gilt-framed sketch she had made of a young Prince Harry, based on television pictures.

But perhaps her best-known non-royal works were sketches of UK prime ministers.

'Biggest head in London'

For several years Mrs Pannett was employed by the Illustrated London News to draw sketches of the view from the gallery of the House of Commons, where she was given her own seat. This was decades before TV cameras were allowed in the chamber.

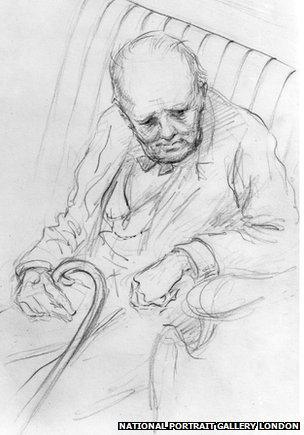

Almost 50 years ago, she captured one of the most poignant scenes in post-War parliamentary life: Sir Winston Churchill's final day in the Commons.

Mrs Pannett sketched the 89-year-old war leader, now stooped and rather gaunt, in his seat.

And she got down a brief scribble as he shuffled out of the chamber for the last time, as Parliament dissolved ahead of the 1964 general election.

It was simple but full of wistfulness. Churchill's life's work was done. Within four months he was dead.

Mrs Pannett had already been commissioned to draw Prime Minister Sir Alec Douglas-Home earlier in the year, who told her he had "the biggest head in London" and he could not get a hat to fit him.

Several other holders of the office were drawn over the years.

Of Edward Heath, Denis said: "I remember her telling me how they played music during his sitting. He was very keen on classical music."

Thatcher's thanks

James Callaghan, meanwhile, was on friendly terms with Mrs Pannett: "Mother used to go to dinner and lunch with friends who were friends of the Callaghans. The friends were the most unlikely Labour people. They had a house in Eaton Square."

"She had a very nice letter from Margaret Thatcher, a thank you letter, after drawing her," Denis recalled. "She had that framed and displayed it in her drawing room."

Such courtesy was not unusual: "Everybody was very nice, really. I don't think she had any unpleasant sitters."

Churchill left Parliament at the age of 89

Juliet Pannett, née Somers, had an exotic background. Her father was a professional gambler who went bankrupt and one of her mother's ancestors was Shakespeare's wife Anne Hathaway, according to family legend.

She married Major Rick Pannett, who had been shot through the mouth in the First World War. The bullet had missed all bones, piercing only the cheeks, leaving him with dimple-like scars and no further damage.

After having two children, Mrs Pannett gave up painting for a few years and suffered from depression, which lifted after she returned to her art.

But the major, who had seen the worst of the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917, was keener to settle down than his wife.

"My father, being a bit older than my mother, was very much keener on a quiet life at home,", said Denis, "but he had to keep being sociable and welcome sitters."

Mrs Pannett developed her skills at art college in Hove, East Sussex, where she grew up and practised on Sussex characters such as rabbit-catcher "Stumpy" Arnold and a shepherd called "Old Drip".

She also played cricket at a high level and sketched figures such as the Sussex and England great Maurice Tate and former England captain Bob Wyatt.

It is now almost a quarter of a century since she painted the Queen and half a century since Churchill prepared to leave the Commons.

But Juliet Pannett's pictures are still in demand for use in books and other publications and she has 22 works in the permanent collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

"It's wonderful that she's so fondly remembered and highly regarded," her son said.