Shining a light on a dark art

- Published

- comments

I've now seen two superb dramas, this year, which have centred on the fine art of parliamentary whipping.

The first was Lincoln, where the plot centred on the President's attempts to persuade the US Congress to abolish slavery. The second, which I saw last night, was James Graham's wonderful play, This House, being played to packed houses at the National Theatre, external.

Both shed light on the messy business of persuading elected representatives to vote for something - and anyone who thinks whipping is an inherently evil and corrupt process should go and see both.

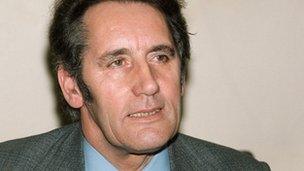

Even in old age, Walter Harrison could be "pretty scary"

This House is set in the Labour and Conservative whips offices in the House of Commons, between 1974 and 1979, when the then Labour government needed extreme whipping to survive, in the face of economic crisis and precarious parliamentary support.

It went from a minority government, to the narrowest of majorities, back to minority status again, as death and defections eroded its numbers. The rival teams of whips, Humphey Atkins and Bernard "Jack" Weatherill, on the Conservative side; and Bob Mellish and Walter Harrison on the Labour side, scheme, manoeuvre and scramble through a series of crises and confrontations. Ill and dying MPs are stretchered into Parliament to vote, the smaller parties are bribed and cajoled, awkward squad MPs are browbeaten and begged.

There's a wonderful scene where the former minister John Stonehouse stages a Reggie Perrin-style disappearance on a beach in Florida, to the contemporary strains of David Bowie's Rock 'n Roll Suicide, only to reappear to face charges of fraud and false accounting, while Harrison insists he can't resign his seat, because the government can't afford to lose a single vote.

There's an odd code of honour between the two teams of whips, and the consequences when it is violated are dire. Harrison is accused of breaking a "pairing" agreement by which MPs from one side who are absent from a vote are cancelled out, by agreement, by MPs from the other side being sent home. Co-operation is withdrawn - and the ill and the dying are forced to attend endless late night votes, and the strain sends more and more MPs to the hospital or the grave.

At the climax of the play, the Labour government faces defeat in a No Confidence vote, and Harrison declines to summon the dying Alfred "Doc" Broughton from his Yorkshire constituency. His last throw is to insist that Weatherill, his opposite number, should honour an agreement to "pair" ill MPs, even though it would mean the government survived, and Weatherill would be finished in Conservative politics.

Weatherill honourably agrees; Harrison balks at finishing him… and the government falls, by a single vote.

And it's a true story. I stumbled across this small footnote to political history in 2004 when I made a documentary for Radio 4 on the 1979 Confidence vote. By then, Jack Weatherill was a peer, having been a distinguished Speaker of the Commons. And Walter Harrison was retired and living in his home town of Wakefield. Despite his legendary exploits as a whip, he was never given the peerage he might have expected…and when Lord Weatherill put me in touch with him, he asked me to report back on his health and comfort, after I travelled up to interview his old sparring partner.

Even in old age, Walter was pretty scary. He told his story in his way, steamrollering over any interjections from me, with perfect recall of his dealings with minor but vital players in the Confidence Vote saga, like the independent republican MP, Frank McGuire. He, on his rare visits from Fermanagh and South Tyrone, had to be kept entertained by a relay of Labour whips, who'd sit and drink with him until each slipped under the table, to be replaced by another colleague.

He monitored the health and sanity of numerous colleagues, fathomed the shifts of opinion and tactics in a dozen smaller parties and monitored the micro politics of every aspect of Westminster life. He fought long and hard to keep his government alive, but ultimately, he wasn't prepared to kill "Doc" Broughton, or ruin a friend on the other side, to buy it a few days of extra life.

What This House does is reveal the seldom-seen side of parliamentary life. The code of honour, the curious friendship, the mutual respect, that somehow co-exists with furious partisanship and festering class resentments and prejudices.

It's not hypocritical, they're not all the same, but they have to work together in order that a democratic Parliament can function.

This House may be a work of imagination, but it has a core of real authenticity.

This House will be showing at cinemas from 16 May, external.