Analysis: Arthur Scargill's silence over Thatcher death

- Published

Arthur Scargill was last year hailed by supporters as the "greatest union leader"

One survivor of the Thatcher decade whose voice was not heard reflecting on the death of the former Prime Minister was that of Arthur Scargill, leader of the National Union of Mineworkers during the fateful pit dispute of 1984-5.

Scargill, now 75, has refused all requests to comment on Margaret Thatcher's premiership and his epic struggle with her government.

In recent years he has rarely answered reporters' questions and made a point of not talking about either himself or his health; he does appear occasionally in public at miners' events and has also been engaged in a protracted court case over his continued use of a union-owned flat in London's Barbican.

I could not help but reflect on Scargill's absence, as I spent two hours on the BBC's local radio circuit on the Tuesday morning after her death, giving interviews to the local radio stations serving the former coalfields of Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire, the presenters told their listeners Scargill had rejected all requests for interviews and they asked me why.

Personally, I was not at all surprised by Scargill's response.

There was no way he was going to be tempted to dance on Lady Thatcher's grave because he knew he would be forced to try to defend the strike he led, his union's crushing defeat and the subsequent devastation of the mining communities.

Industrial muscle

Scargill has rarely been heard in recent years and the reason is straightforward: he is determined not to allow reporters to chip away at what he believes was the NUM's "victory" which was the struggle itself and the miners' refusal during their year-long strike to bend the knee to Margaret Thatcher.

My last interview with him was in February 2012 at a rally in Birmingham to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Battle of Saltley Gates, when as an up-and-coming NUM activist he organised the flying pickets which succeeded in closing the Saltley coke depot, forcing the then Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath to concede a 27% pay increase.

Scargill was introduced at the 2012 rally as the "greatest trade union leader this country has ever seen".

Here was the former NUM President immortalising himself as a working class hero through his description of the day he urged 15,000 of Birmingham's engineering workers to join the striking miners.

"I said at the Bull Ring you can either stand on the side and walk and watch what happens or join us and march into history and in my words become immortal in the working class; to their eternal credit they joined the miners," he told the crowd.

Two years after Saltley Gate, Ted Heath was forced by another miners' strike to go to the country and ask electors who ruled Britain.

Heath's defeat in 1974 and the re-election of a Labour government helped entrench the NUM's industrial muscle.

Mass redundancies

After being elected Yorkshire President following his success at Saltley, Scargill became NUM President in 1981 and the scene was set for the 1984 dispute when, in defiance of the government's demand that 20 uneconomic mines should be closed with the loss of 20,000 jobs, the strike went ahead without the endorsement of a pit head ballot.

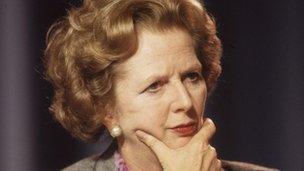

Lady Thatcher: Well matched with Arthur Scargill?

Scargill believed the NUM would win the dispute; he was convinced that coal stocks would eventually be exhausted and that Mrs Thatcher would have to give way.

But she mobilised the forces of the state against the NUM: The power stations were told to burn all the oil they needed to in order to keep the lights on and the police were encouraged to use all the force they thought was necessary to restrain the miners' and to keep the pits open for those miners who wanted to work.

Thatcher and Scargill were well matched. The prime minister was able to distance herself from the impact of mass redundancies and a jobless total that topped three million, just as the NUM President was able to insulate himself from the hardship in mining communities as the strike dragged on month after month.

In his day Scargill was easily the most effective communicator in the labour movement; like so few of his trade union contemporaries he knew how to get the news media dancing to his tune.

Although the NUM has now severed all its links with its former President, Scargill has no intention of allowing the news media to rewrite his own take on the 1984-5 strike.

He believes the struggle itself was a working-class victory and that he will go down in British trade union history as the only leader who never betrayed his members, a version of his own life story that I think he will take to his grave.