History of political lobbying scandals

- Published

Three peers and an MP have been accused of agreeing to do parliamentary work for payment after undercover reporters for the Sunday Times, BBC Panorama and the Daily Telegraph posed as lobbyists.

But the allegations levelled at Lord Laird, Lord Cunningham, Lord Mackenzie of Framwellgate and Patrick Mercer, all of whom deny wrongdoing, are just the latest flashpoint to bring the issue to the fore.

Here's a look back at some of the most high-profile lobbying scandals of the past.

'Cash for Cameron'

Mr Cruddas stepped down as Tory treasurer and the Conservatives launched an investigation

In March 2012, Conservative Party co-treasurer Peter Cruddas resigned after secretly filmed footage showed him apparently offering access to the prime minister for a donation of £250,000 a year.

He made the claim to Sunday Times reporters posing as potential donors. He said £250,000 gave "premier league" access, including dinner with David Cameron and possibly the chance to influence government policy.

At the time Mr Cruddas, a multi-millionaire businessman who runs a charity to help disadvantaged young people, said he regretted "any impression of impropriety arising from my bluster" and the Conservatives said no donation had been accepted or access offered in return for money as a result of the conversations involving Mr Cruddas.

However, the disclosures did lead to David Cameron revealing details of all meetings he had had with substantial Conservative donors at No 10 and Chequers since becoming prime minister.

Labour leader Ed Miliband also published details of meetings with his party's major backers.

'Doing it because we asked him to'

Tim Collins was a Conservative MP from 1997 to 2005

In December 2011, the Independent, external claimed that Tim Collins, a former Conservative MP and Bell Pottinger executive, had boasted of the public affairs company's access to government to undercover reporters.

Mr Collins told reporters from the Bureau of Investigative Journalism: "I've been working with people like Steve Hilton, David Cameron, George Osborne for 20 years-plus. There is not a problem getting the messages through."

He also reportedly claimed that Bell Pottinger had persuaded the prime minister to raise the matter of copyright infringement with Chinese premier Wen Jiabao on behalf of engineering firm Dyson.

"He was doing it because we asked him to do it," he said.

Downing Street said the reported claims were a "gross exaggeration". It denied copyright infringement was raised with the Chinese at the behest of the company and said Bell Pottinger was not able to exert undue influence on the government.

Liam Fox and Adam Werritty

Adam Werritty (centre, head bowed) accompanied Liam Fox on a trip to Sri Lanka

In October 2011, Defence Secretary Liam Fox resigned following pressure over his working relationship with friend and self-styled adviser Adam Werritty - a former flatmate of Mr Fox who was best man at his wedding.

Mr Werritty visited Mr Fox in the Ministry of Defence on a number of occasions, was allowed to accompany him on foreign trips where he met diplomats, defence staff and defence contractors, and had handed out business cards suggesting he was Mr Fox's adviser, despite having no official role in government.

Questions were also raised about who had paid for Mr Werritty's business activities and whether he had personally benefited from his frequent access to the defence secretary.

When he resigned, the former defence secretary said he had "mistakenly allowed" personal and professional responsibilities to become "blurred" but maintained there had been no impropriety.

An investigation by then Cabinet Secretary Sir Gus O'Donnell found Mr Fox had "clearly" breached the Ministerial Code, but he was cleared of making any financial gain through the relationship or breaching national security.

Subsequently, the government agreed to tighten rules on who should accompany ministers to official meetings.

'Cab for hire'

Stephen Byers said he would work for up to £5,000 a day

In March 2010, an undercover sting by the Sunday Times and Channel 4's Dispatches programme alleged that three former Labour cabinet ministers were willing to help a lobbying firm in return for cash.

Stephen Byers, a former transport secretary, was filmed saying he was like a "cab for hire" who would work for up to £5,000 a day.

Former Defence Secretary Geoff Hoon said he wanted to make use of his knowledge and contacts in a way that "makes money" and that he charged £3,000 a day.

Former Health Secretary Patricia Hewitt was alleged to have claimed that she helped to obtain a key seat on a government advisory group for a client paying her £3,000 a day.

All three were suspended from the Parliamentary Labour Party "for bringing it into disrepute". A subsequent investigation by Parliament's Standards and Privileges Committee found Mr Byers and Mr Hoon guilty of a "serious" breach of parliamentary rules, while Ms Hewitt was cleared.

Mr Byers said he "should not have spoken in such terms", while Mr Hoon acknowledged he had got it "wrong" in giving the impression he wanted to profit from his government contacts.

As leader of the opposition at the time, David Cameron said the revelations would make people think all MPs were "sleazy pigs".

'Cash for amendments'

Lord Taylor was suspended from the House of Lords following the revelations

In January 2009, four Labour peers - Lord Truscott, Lord Taylor of Blackburn, Lord Snape and Lord Moonie - were the subject of an undercover investigation by the Sunday Times.

The newspaper claimed its reporters had approached the men, pretending to be lobbyists acting for a company that wanted help getting an exemption from laws on business rates.

It alleged that all four had offered to help make amendments to legislation for up to £120,000.

A House of Lords committee investigated the peers and found Lord Taylor and Lord Truscott had breached the Lords Code of Conduct by failing to "act on their personal honour". But Lord Snape and Lord Moonie were cleared of wrongdoing.

As a result, Lord Taylor and Lord Truscott became the first members of the House of Lords to be suspended since 1642.

'Lobbygate'

Derek Draper was a political lobbyist and former Labour special adviser

Political lobbyist Derek Draper was caught by the Observer boasting about his links to Downing Street in July 1998.

On the recording made by journalist Greg Palast, Mr Draper, a former special adviser, reportedly said: "There are 17 people who count in this government ... [to] say I am intimate with every one of them is the understatement of the century."

Following the report, Mr Draper denied any wrongdoing and resigned from his lobbyist job.

The scandal, which was dubbed "lobbygate", prompted Prime Minister Tony Blair to make his famous remark that "we must be seen to be purer than pure" - not whiter than white, as he is often quoted.

'Ecclesgate'

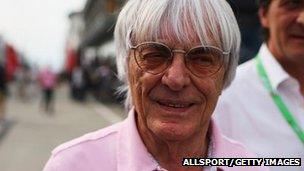

Bernie Ecclestone gave £1m to the Labour Party

The controversy over Labour's relationship with Formula 1 boss Bernie Ecclestone was the first funding scandal to hit Labour after it came to power in 1997.

Labour had committed to ban tobacco advertising in its election manifesto, but a few months into government it announced that Formula 1 would be exempt from the ban.

It emerged that the party had received a £1m donation from Mr Ecclestone in January 1997 - before the general election.

After seeking advice, Labour returned the donation. The party and Mr Ecclestone claimed that the donation had had no connection with the decision to exempt F1.

However, Tony Blair did use a TV interview to apologise for the government's handling of the affair saying he "took full responsibility for that", although he did not apologise for the decision to exempt F1.

It was in this interview that he said the much-quoted phrase: "I'm a pretty straight kind of guy."

'Cash for questions'

Neil Hamilton sued Mohamed Al Fayed for libel and lost

In 1994 it emerged that a number of individuals within the Conservative party had agreed to submit questions to Parliament in exchange for money.

The revelations, which came to be known as the cash-for-questions scandal, tarnished John Major's administration and overshadowed the last years of his Conservative government.

Conservative MPs Neil Hamilton and Tim Smith were accused of taking cash in brown envelopes from Mohamed Al Fayed, the then owner of Harrods, to ask questions in the Commons.

The claims were made in the Guardian newspaper and supported by Mr Al Fayed himself.

Ian Greer, as head of lobbyists Ian Greer Associates, was said to be the middleman in the transactions.

Mr Smith admitted to the payments and resigned immediately, but Mr Hamilton protested his innocence. He was, however, forced to resign as corporate affairs minister.

He also lost in parliamentary seat in 1997, ousted by independent candidate Martin Bell who stood on an anti-sleaze ticket.

Mr Hamilton and Mr Greer issued libel writs against the Guardian, but these were eventually dropped. Mr Hamilton also sued Mr Al Fayed for libel and lost.

The scandal led John Major to establish the Committee on Standards in Public Life (under its first chairman, Lord Nolan) to address wider concerns about declining standards in Parliament and in public life generally.

- Published3 June 2013

- Published2 June 2013

- Published1 June 2013