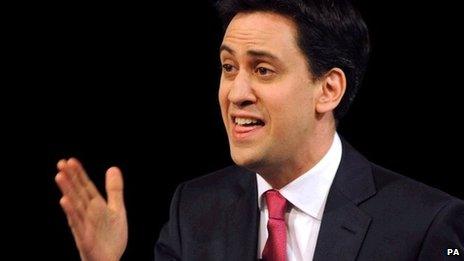

How can Ed Miliband stop the unions row?

- Published

Labour and the unions are in a seemingly irresolvable disagreement over their future funding relationship. So, where does Ed Miliband go from here?

What began as a local spat over the selection of a Labour candidate for the general election in Falkirk has become the dominating theme of the Trades Union Congress.

This is now about much more than what may, or may not, have happened in a town in central Scotland.

It is, instead, a much deeper question about the Labour movement, its finances and its leadership.

Bickering

Ed Miliband insists ending the automatic affiliation of millions of union members to Labour - unless they choose to opt out - is a reform long overdue. Instead trades unionists should choose to opt in, he argues

Everyone here seems to have a view, although not everyone is encouraged to express it.

Some unions have banned their delegates from speaking to the media, unless they get permission first. It is an insight into the twitchiness and the anxiety this issue is provoking.

There is open disagreement. Disagreement over the principle of Mr Miliband's idea. Disagreement, too, about the implications of attempting this change now.

To some this is necessary modernisation.

To others it projects an image of bickering over internal reform.

Paul Kenny, the leader of the GMB, is so incensed that in one round of interviews he was picking a different colourful insult about the idea for each one.

Firstly it was "dusted down from an old schoolboy project"; next it was "something dreamt up after a bad night out."

'Opportunity cost'

For Dave Prentis, the general secretary of Unison, it is not the principle of the idea he opposes. After all, his union has an opt-in model for Labour contributions already.

Mr Prentis's concern is about the impression it leaves.

There is plenty of evidence that electorates all over the turn their noses up at divided parties. Hence his desire for Labour in the UK to learn lessons from its divided Australian counterpart, recently defeated in a general election.

Other leaders have been striking a more emollient tone, among them Frances O'Grady, the general secretary of the TUC, and Len McCluskey, of Unite.

Ms O'Grady was determined not to dwell on the row about Labour's links to the unions, and focus her fire instead on the Conservatives.

Those around Ed Miliband emphasise he is of firmer mind now than ever to push ahead with his planned change.

And he has marched sufficiently far up this hill that it would be a humiliating descent if he had to clamber back down.

The challenge for Labour, regardless of whether his plan is a good one and how much money it may or may not cost the party, is "opportunity cost".

Or to put it another way, how it is going down in Stourbridge or Cannock Chase?

People's appetite for politics is finite and so there is a trade-off when a particular news story is commanding a lot of attention.

It means another one, potentially about an issue that matters more to more people, isn't.

This whole issue will remain a talking point in the Labour movement until next Spring, when the party holds a special conference to resolve it.

And by then, it will be just 12 months until the people of Stourbridge, Cannock Chase and everywhere else will be asked whether Labour is ready to run the country again.

- Published9 July 2013

- Published8 September 2013

- Published8 September 2013

- Published7 September 2013

- Published4 September 2013

- Published9 July 2013