Party conferences: What's at stake for the leaders?

- Published

Party conferences can seem a contradiction in terms.

Not much conferring appears to go on. And the parties tend to be rubbish.

But that does not mean they do not matter.

The annual tour of Britain's cities allows our politicians a brief moment front of stage where they gain publicity and scrutiny.

And while corporate lobbying and media confection have long since replaced any genuinely democratic gathering of grassroots members, today's conferences still focus parties' minds and quicken pulses.

This year these furrowed brows and racing hearts are driven by one word: doubt.

All three leaders of the largest parties want to use their conferences to dispel doubt about them, their parties and their policies.

The field of battle will be the economy and living standards. And this will matter because these conferences are the penultimate before the general election, ones that will shape the terms of the campaigns ahead, the manifestos soon to be written and the opinions of an electorate whose fickle intentions few politicians dare to predict.

Liberal Democrats (14 - 19 September, Glasgow)

Nick Clegg perhaps could have wished for fewer distractions ahead of his conference: Sarah Teather's anguished retirement; Chris Huhne's attempted self-absolution and Lord Oakeshott's traditional demand for the Lib Dem leader's head.

Mr Clegg could also probably have done without the elliptical utterances of some of his colleagues such as Tim Farron: "The electoral system is a fruit machine" and Steve Webb: "God is a liberal but not a Liberal Democrat."

But in fact Mr Clegg comes to Glasgow in better shape than some had expected.

There is no serious threat to his leadership.

None of his MPs has abandoned the party in frustration over the coalition's direction (although Miss Teather has decided to quit Parliament) and the Eastleigh by-election victory earlier this year showed the party can still hold seats against the tide.

Nick Clegg, pictured here with wife Miriam, is in better political shape than expected

Cause for concern comes from opinion polls that suggest the party is scraping its way into double figures behind UKIP.

Nick Clegg's task at his conference is to dispel the doubts that his party can recover in time for 2015.

His pitch will be that the Lib Dems must gain credit for the emerging economic recovery and drive home the idea that they are a competent party of government.

And that means not breaking from the Tories before the election and, in the words of Lord Ashdown, "governing up to polling day".

Expect much talk of the need for the Lib Dems to hold their nerve.

This strategy also means the party will campaign explicitly as a future coalition partner, one that can moderate the excesses of the larger parties.

This approach will be challenged from the liberal left. They will argue that the party needs to detach itself from the coalition sooner rather than later and establish a policy agenda that distinguishes them from the Conservatives and makes them more appealing to left-wing voters.

So there will be demands for a 50p top rate of tax, a super mansion tax, a cut in tuition fees and a softening of austerity.

What makes this debate matter is not just that the Lib Dems could be part of a coalition after the next election and the policies discussed in Glasgow could form part of future coalition agreement.

What makes this debate crucial is that it could determine what kind of coalition is formed in the future.

If the arithmetical result of the election allows for a coalition with either Labour or the Conservatives, then the debate between left-inclined social democrats and fiscally-conservative liberals could decide whether or not David Cameron or Ed Miliband is prime minister. Food for thought.

Labour (22 - 25 September, Brighton)

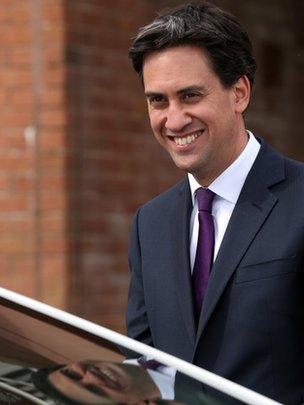

Ed Miliband comes to Brighton narrowly ahead in the opinion polls, fresh from a victory of sorts over the crisis in Syria when his decisions ensured British forces would not take part in any military action.

He has spent the year developing his One Nation theme and slowly outlining at least some policies, the most important of which was the party's broad acceptance of the government's spending plans.

But his task, too, is to dispel doubts in the minds of his party and the wider electorate about the strength of Labour's poll lead, about its economic policy now that a recovery of sorts is under way and about the direction of his own leadership.

His aim will be to try to reassure voters that Labour has something to say about the economy apart from insisting that the growth we are seeing is weak, unfair and potentially unsustainable.

Ed Miliband is expected to focus on a single core theme - living standards

And that something will be living standards.

Mr Miliband's whole focus, we are told, will be on what he calls the cost of living crisis, namely that real wages are falling while youth unemployment is rising.

And the policy announcements to expect will focus in this area, such as promises to help with child care, energy bills and low wages such as through the living wage, perhaps by offering tax breaks to companies that pay it.

He will not distract himself from this theme, I am told by Labour sources, by announcing a new policy on a European referendum as has been speculated.

What will provide some distraction will be Mr Miliband's continuing attempt to change his party's relationship with the trade unions.

Lord Collins will publish his interim report setting out Labour's broad intentions.

There will be no firm details but there will be enough to divert the news cycle for a day and wind up some union leaders.

And yet underlying all this will be the continuing debate within the party about Mr Miliband himself.

There appears no threat to his leadership but equally there appears little confidence, certainly among some MPs frustrated by what they see as a wasted summer when the party seemed to walk off the political pitch.

There is a nervousness among some in Labour that voters still do not quite know what an Ed Miliband premiership might look like.

So his challenge - in his interviews and speeches - is to address those concerns and paint a picture of a future Labour government.

The patience of some in his party is growing thin.

Conservatives (29 September - 2 October, Manchester)

Despite everything, David Cameron could be forgiven for arriving in Manchester with a modest spring in his step.

He has spent much of this year at odds with his party over a European referendum and gay marriage. He has suffered electorally at the hands of UKIP. He has been defeated in the House of Commons over taking the country to war.

David Cameron's MPs are daring to dream of a Commons majority

And yet the arrival of a modest economic recovery has put some hope into Conservative hearts, allowing them to dream once again of the possibility of winning a majority at the next election.

"The economics is changing the politics," one Tory minister told me.

Tory MPs do not feel under pressure from Labour. They think they have a strong message too on crime, welfare and immigration.

And yet the doubt remains.

Can Mr Cameron really win a majority over Ed Miliband when he failed to do so against Gordon Brown?

That is the question that will be hanging over the Conservative conference.

The prime minister's answer, in part, will be to accept that the promise of economic recovery will not be enough.

The Conservatives will also have to show they are on the side of people who are suffering from falling living standards. Hence the conference theme and slogan: "For hardworking people."

There will be lots of talk of how the government has cut income tax and created more jobs and there will be announcements designed to help people with the cost of living.

Oh and the Mayor of London, Boris Johnson, I am told, will be on best behaviour so there will be no distractions.

We shall see.

UKIP (20 - 21 September, London)

Nigel Farage is aiming to win next year's European elections

Nigel Farage goes to his conference after an astonishing year when UKIP has exploited growing voter dissatisfaction with the mainstream parties.

At the local elections, UKIP won 23% of the projected national share of the vote, seeing the party's tally of councillors rise from seven to 140.

The focus at UKIP's conference will switch to next year's European elections where some are already predicting that the party could top the poll.

And yet, like the other parties, there are doubts.

After May's victories, UKIP has struggled to stay in the public eye. It has suffered the odd resignation and defection. And it has lost some council by-elections.

A natural lull, say some. Proof, say others, that the fourth party breakthrough is still a work-in-progress.