Nick Clegg told to ditch goal of 'social mobility'

- Published

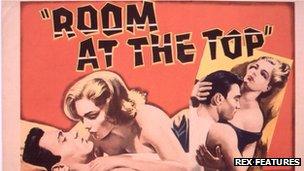

Social mobility was all the rage in the 1950s and 60s

Social mobility is a "comforting illusion" that is nearly impossible to achieve and politicians should not waste their valuable time pursuing it.

Tony Blair's former speech writer Philip Collins did not sugar coat his message when he addressed a lunchtime fringe meeting organised by the Social Market Foundation. Social mobility, he argued, was a "terrible objective".

The strange thing was that, instead of provoking a riot, or accusations of heresy, as might have been expected at a gathering of socially conscious Liberal Democrats, everyone in the room agreed with him. Including the head of the Child Poverty Action Group.

Lib Dem deputy leader Simon Hughes even said he had attempted to persuade Nick Clegg to stop talking about it.

"I have failed so far to persuade him to drop the words 'social mobility' from the government lexicon and to drop the words 'pupil premium' which again, nobody on the Old Kent Road has ever referred to.

"More money for poor kids is a phrase they understand. And helping people do better in life they understand."

He added: "Social justice, fairness and equality are much better things for us to be concentrating on."

'Pupil premium'

Talking about boosting social mobility is something modern political leaders like to do a lot. It's right up there with "hard working families".

But, argued Philip Collins, now chief leader writer for The Times, they can't possibly mean it.

Improving childcare and educational standards, and fighting poverty, were all important things that got done in the name of social mobility.

But there was no evidence that any of these things actually helped people born into the working class rise up the social scale, he argued.

The growth of the middle classes in the 20th Century was driven by changes in the labour market - more jobs for lawyers, accountants and managers.

It was a "serious" problem if that had now stalled, said Collins, but there was little politicians could do about it, unless they completely changed the shape of the British economy.

Measures like the Lib Dems' cherished "pupil premium," which gives extra funds to schools for each child who currently qualifies for free school lunches, would have no effect, he claimed.

Collins said he had tried to persuade Nick Clegg's team not to "set up social mobility as your test," he told the meeting, but no avail.

"It's very difficult to achieve, it's extremely complex, we don't know how to do it. Nobody knows how to make it popular, nobody can talk about it a way that any normal person can understand.

"It is, in every single respect, a terrible objective for a politician."

'The dull child'

As someone who grew up in a "less salubrious" part of Manchester, Collins admitted he was a classic example of someone who had moved up the social ranks.

Simon Hughes thinks social justice is a better objective

But, he argued, there was not - to borrow a phrase from the golden age of social mobility, the 1950s - Room At The Top for everyone.

There was only a finite number of well-paid, professional jobs.

"The children of the wealthy, the children of the previously mobile generation, such as me, will help their children to a greater extent," said Collins.

"So to close that gap is a much harder thing to do and I can't think of a single education reform in the 20th Century that had a marked impact on relative social mobility at all. Not one.

"It's a comforting illusion, I think, that if we just do a whole load of things in education, or in childcare, then it will all be better. It won't. Childcare will be better and that's good but social mobility will not necessarily be better at all.

"The dull child of the middle-class parent has to come down the rung in order for me to go up, otherwise you don't have social mobility."

He added: "No British politician is going to to go on the hustings and say what I want is for your children to go down the social ladder. It's a ridiculous message."

It was a thought provoking argument, eloquently put, and just for a moment, none of the politicians, party activists and policy wonks that had crowded into the sweltering, airless meeting room at the Scottish Exhibition Centre to listen to Collins felt much like talking about their favourite hobby horse.

- Published16 September 2013

- Published16 September 2013

- Published16 September 2013

- Published16 September 2013