How fixed-term Parliaments have changed politics

- Published

Fewer general elections

We know that the next election will be in May 2015, five years after the last one. But the average length of time between general elections since 1945 has been three years and 10 months. Now, as a result of fixed term parliaments we are going to get one every five years. That means over the next 100 years there could be six fewer general elections. Good news for political phobics (ie everybody outside Westminster). But what about democracy?

No more "zombie" governments

In the old days, when governments went into a fifth year you could almost smell the decay and desperation - the sense that the incumbents were just hanging on in the hope that something - anything - would turn up to transform their dismal electoral prospects. That does not happen any more. But some fear the paralysis in government will be just as bad - but for a different reason...

Very long election campaigns

Far from keeping campaigns to a tightly focused few weeks before polling day, which was the original idea, fixed-terms appear to have had the opposite effect. It is still possible for a general election to be held before the five years is up through a no confidence vote in the Commons. But that seems unlikely. What seems more likely is that we are in for 16 months of steadily escalating electioneering. Lucky us.

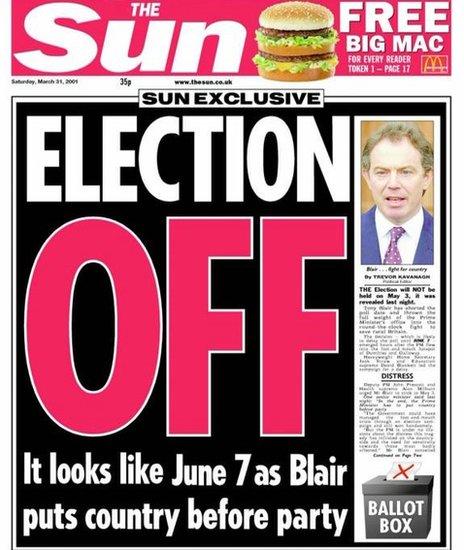

The media have lost one of their favourite games

The tabloid press used to go to extraordinary lengths to get hold of the date of the next election. The Sun, in particular, used to pride itself on scooping the competition. Not any more.

More coalitions

Without a fixed-term Parliament the coalition may have broken up by now, or at least been buffeted by a frenzy of press speculation about snap elections. In fact many insiders reckon it is unlikely the Lib Dems and Conservatives could have got together in the first place without first agreeing to make fixed term parliaments a key policy.

Better planning

Civil servants love stability - and knowing exactly when the general election is going to be held takes a lot of the uncertainty out of long-term planning. Single party governments with a decent majority are likely to gain the most, according to constitution expert Peter Riddell in a 2011 select committee inquiry., external

Boring party conferences

Without the tension created by an election that could happen at any time these annual shindigs seem to have become even more stale and stage-managed. Particularly in the mid-term period. It might just be coincidence, but where is the drama?

The incumbent loses a key advantage

The power to choose the date of the election is traditionally seen as handing a huge advantage to the party in power. But it can prove a curse as well as a blessing. Just ask Gordon Brown, whose last minute decision not to go to the country in 2007, after allowing speculation to grow that he would, probably cost him his best shot of winning a mandate of his own.

Ad men and pollsters out of pocket

Spending on election advertising actually went down at the 2010 general election to a total of £31.1m, thanks largely to a big drop in the amount Labour managed to raise under Gordon Brown. It is likely to go down further still when the parties no longer have to block book poster sites for weeks on end in preparation for a likely poll. And then there are the opinion pollsters. Election speculation is their bread and butter too.

Less accountability?

Fixed four-year terms are the norm in many countries around the world. They used to be the norm in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland too, but elections for the devolved assemblies are moving to five year terms to avoid clashes with Westminster elections. Some argue four year terms give voters more opportunity to hold politicians to account. Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg pushed for a five year term, arguing it provided greater stability. And that is where we are, unless a future government decides to change it...