Should UK accept lower growth to cut immigration?

- Published

Is lower economic growth a price worth paying for cutting immigration, as Nigel Farage claims?

Saying you wouldn't mind seeing lower economic growth would be career suicide for most politicians.

But Nigel Farage has built his career on saying the unsayable.

The UKIP leader says he does not accept that there will be lower economic growth if mass immigration is curtailed, but if there is then "so be it".

"Actually, do you know what, I'd rather we weren't slightly richer and I'd rather we had communities that felt more united and I'd rather have a situation where young, unemployed British people had a realistic chance of getting a job," he told BBC News.

"So, yes, I do think the social side of this matters more than pure market economics."

Some will see this as xenophobia - a measure of how uncomfortable UKIP are with modern, ethnically diverse Britain.

Others will suspect political opportunism in former City trader Farage's apparent conversion from dyed-in-the-wool free marketeer to proto-hippy, who thinks there is "more to life than money".

But does he have a point?

Lower mortgage rates

The economic boom of the early 2000s was built, in part, on an unexpected flood of cheap, and highly motivated, workers from Eastern Europe.

The then Bank of England Governor Mervyn King acknowledged that this held wages down far longer than would normally have been the case, leading in turn to lower mortgage rates.

This has changed all of our lives in big, and small, ways.

Nigel Farage and Theresa May are at odds over immigration

Property prices soared, on the back of low interest rates.

Fresh fruit and vegetables in supermarkets remained suspiciously good value for money, thanks to a willing, low paid workforce toiling in the fields and market gardens.

My colleague Nick Robinson can still get a haircut for £8 in Central London thanks to his Romanian barber (as he revealed on the BBC News Channel earlier).

The downside - according to Labour leader Ed Miliband - is that British business has been left with a "chronic dependence" on cheap foreign labour.

This is great for the profits of "unscrupulous" companies but disastrous for those who have seen their wages held down and job opportunities shrink as a result of it, argued the Labour leader in an article for the Independent on Sunday, external.

Thousands of migrants work on British farms

Mr Miliband's solution is not to close the door to migrants, and get Britain out of the EU, as Mr Farage wants, but to make companies pay their workers more and to stop employment agencies gaming the rules.

Conservative ministers have made great play of clamping down on "benefit tourists" as the UK opens its doors to a fresh wave of migrants.

They have stuck to the argument that immigration has, on balance, been good for Britain's economy - something borne out by most academic research into the subject - and that a growing economy will create jobs for everybody.

But Conservative Immigration Minister Mark Harper last month also told the boss of Domino's Pizza - who had implied immigration restrictions were making it difficult to fill vacancies - that he should consider paying higher wages to recruit more staff.

The fact is that there are chronic skills shortages in some parts of the British economy. A glance at the official shortage occupation confirms this, external.

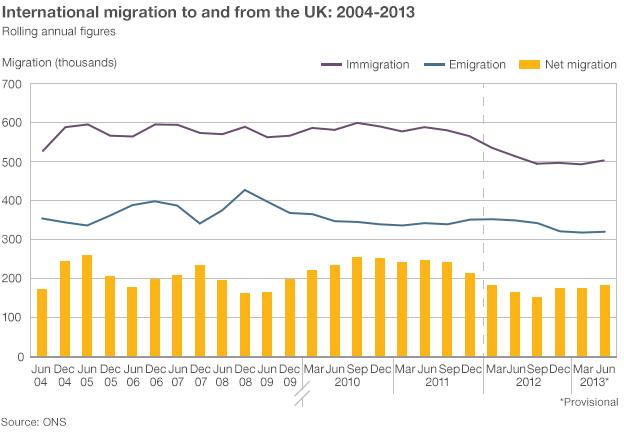

The Conservatives still hope to cut net immigration to below 100,000 a year by 2015, even if that target is looking increasingly unlikely to be met.

But at the same time, they have redoubled their efforts to attract the "brightest and the best" from outside the EU, announcing a special "VIP" visa for wealthy foreign business executives.

They are also making it easier to visit the UK from China, which is now the biggest source of immigration into the country, thanks to large numbers of students (40,000 people came to the UK from China last year).

Business Secretary Vince Cable - who has been openly hostile to the migration target from the start - has been on a mission to reassure foreign students in India and other fast-growing nations that - despite what they might have heard from the UK media - Britain still welcomes them.

The government could, of course, meet its net migration target at a stroke if it took Britain out of the EU, but it is not prepared to do that because of the damage it believes this would do to the economy. We will have a chance to debate that one at greater length, if and when we get an EU referendum.

But, for now, the big question, for those who profess to be concerned about high immigration levels, is how do you get an economy that has changed very little since the heady days of 2007 growing again without a willing army of low-paid workers and access to highly-skilled professionals in shortage occupations?

Perhaps the only answer, as Mr Farage has said, is to accept that money isn't everything.

- Published7 January 2014

- Published5 January 2014

- Published14 May 2014