Lord Rennard row: What does it tell us about Lib Dems?

- Published

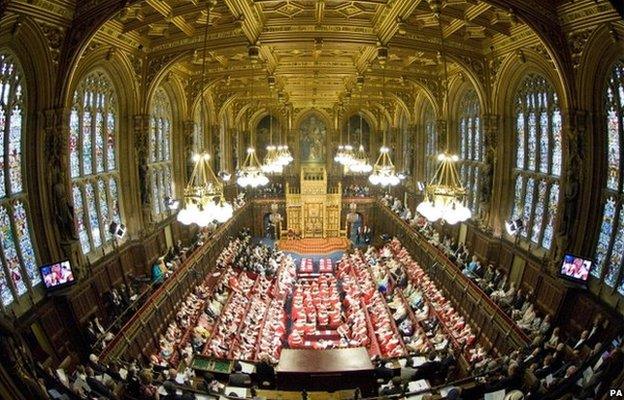

Liberal Democrat peer Lord Rennard is due to rejoin the House of Lords later on Monday

On Monday, Lord Rennard is hoping to resume his seat on the Liberal Democrat benches in the House of Lords.

With exquisite timing, he will do so just as their Lordships gather to discuss anti-social behaviour.

Most peers will be too polite to mention such unfortunate coincidence but some on the naughty benches will raise an amused eyebrow.

For the other political parties are enjoying the Lib Dems' discomfort over what has become known as the Rennard affair. They know that only the Lib Dems could have got themselves into such a mess.

Other parties would have eased Lord Rennard out a long time ago once the allegations of sexual harassment first emerged. Regardless of the rights or wrongs, regardless of what actually happened, no other party would have allowed 10-year-old allegations about the behaviour of a party official to cause so much damage today.

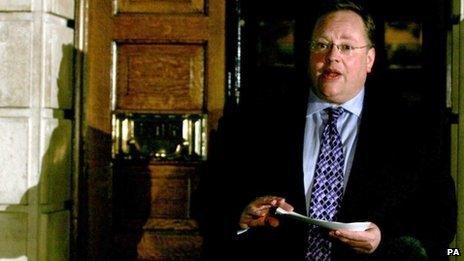

Lord Rennard has always denied the allegations

The fact that the Lib Dems have allowed this to go on for so long tells us a huge amount about the party today:

1. Its obsession with internal democracy is at odds with modern demands for centralised leadership. Nick Clegg has very little power to do anything with Lord Rennard. The only people who can suspend him from the party in the Lords are the chief whip there, Lord Newby, and the Lords' leader, Lord Wallace. If they chose to do that, as looks highly possible, they could be countermanded by a vote of Lib Dem peers. Lord Rennard can also only be removed from the Federal Policy Committee - a body to which he was elected - if the committee itself chooses to expel him, as some members wish to try. The dilemma is that if a party wants to be democratic (the hint is in the name) then it sometimes has to accept that that makes decision-making difficult.

2. There is a huge generation gap between younger and older party members. Older party members, activists and elected representatives grew up marching to Lord Rennard's drum. Many of them owe their careers to Lord Rennard's electoral skills. He had in the party a svengali-like reputation to win and save parliamentary seats. But a new generation of Lib Dems know little of this psephological history and are puzzled by the emotional hold Lord Rennard has over the party. And they are much less forgiving of the kind of behaviour Lord Rennard is accused of than their older colleagues.

3. The Liberal Democrats do not always live up to their reputation for fairness. Many of the complainants talk of their allegations initially being dismissed by the party, of not being taken seriously, of being told to bite their lip. Equally, supporters of Lord Rennard talk of a failure to follow due process, of how unjust and unfair it would be for him to have to apologise for unproven allegations in an unpublished report. A party opposed to secret trials, they say, should not use them against their own members.

4. This is still a party that is growing up in government. Only in a party as small as the Lib Dems could someone like Lord Rennard be so important. Only a party as small as the Lib Dems could have such convoluted disciplinary procedures with different standards of proof required for officials and members. The pressures of office often test the limits of party structures; Labour and the Conservatives know this and are flexible as a result. The Lib Dems still have a party for opposition that is learning to cope with government.

5. The Lib Dems may promote themselves as the party of fairness but boy, can they be tough on each other. When discussing the Rennard affair, Lib Dem peers mutter about failed candidates getting their own back and bitter former employees seeking revenge. Equally, supporters of the complainants have been vicious in their denunciation of a man whose whole life has been the Liberal Democrats and who has lived as an outcast since this began, and whose health has suffered accordingly.

As a result of all this, Nick Clegg now finds himself in a pickle.

Forgive this brief immersion into the murky internal workings of the Lib Dems but the Regional Parties Committee could decide that Lord Rennard's refusal to apologise may bring the party into disrepute.

They could start a new disciplinary process and the Lords Newby and Wallace could use that as a pretext to withdraw the whip from Lord Rennard. But that could be challenged by Lib Dem peers who might demand a vote to overturn the decision.

Nick Clegg said the whip should not be restored unless the peer apologised

Lord Rennard could also challenge the decision to start a new disciplinary process in a high court. One of the complainants could make a civil case against Lord Rennard.

And so on, and so on through spring conferences all the way to the European elections in May.

The consequences of this may well be even fewer votes for the Lib Dems. Younger, particularly female voters may be put off by the image of a party that is perhaps still coming to terms with modern norms of behaviour. And other voters may be put off by a party that still struggles to organise itself in a fair way. And other voters may wonder what Nick Clegg is doing while his party tears itself apart.

Politicians often talk of tough choices. For Nick Clegg, this actually is one.