Briefing papers not 'verbose' enough to be revealed

- Published

- comments

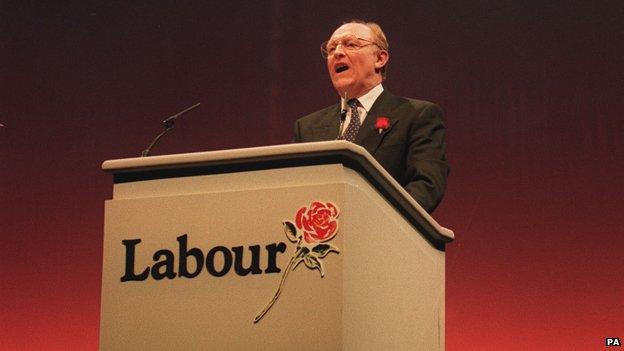

Neil Kinnock during the 1992 general election campaign

As a journalist who often makes freedom of information requests I have come across a range of reasons from public authorities for keeping documents secret.

However I have now encountered a new justification - official briefing papers that apparently cannot be shown to the public because they are too succinct and not verbose enough.

This involves documents prepared by the civil service to brief the then Labour leader Neil Kinnock if he became prime minister following the 1992 general election.

The information commissioner has just ruled that officials would react to the release of these papers by no longer writing "succinct and focused" briefings for incoming prime ministers. He has backed the government view that instead they would compose documents that are "excessively detailed" and "verbose".

Historical interest

I requested the material in November 2012 under the Freedom of Information Act, because I thought it could be of substantial historical interest to learn more about how the civil service prepared for the possibility of Lord Kinnock (as he now is) taking over as prime minister.

Although in fact Sir John Major remained in 10 Downing Street with a 21-seat Conservative majority, a Labour victory had seemed a plausible possibility to many in the run up to the election, in line with much of the opinion polling.

I also thought that since more than 20 years had passed, publishing the information now would not have a damaging effect on the candour of comparable briefings in the future.

After the Cabinet Office rejected my FOI request, I complained to the information commissioner, who has now issued a decision that largely dismisses my appeal.

According to the commissioner's ruling, the government argued that releasing these documents would result in future ones being more verbose.

The ruling says: "It was not asserted that disclosure would necessarily make briefings less frank. Instead the briefings would be drafted with an eye on likely future publication and would be more likely to be excessively detailed - the Cabinet Office used the description 'verbose'."

Upheld

This was the opinion of the attorney general, Dominic Grieve, the minister who normally considers FOI applications that relate to previous governments.

His stance was upheld by the commissioner, who ruled that disclosing most of the material requested would be against the public interest. The ruling states: "In reaching this view, the Commissioner has had particular regard for the public interest in ensuring that briefings for incoming prime ministers in the future are succinct and focused."

The commissioner praises the style in which the briefings are written and concurs that this approach would be less likely in future if this material from 1992 is disclosed now.

Ironically Lord Kinnock himself had a reputation for verbosity, but it's not clear whether this is connected to the determination of officials to write succinct briefing papers for him.

The commissioner does not entirely back the government. He criticises the Cabinet Office for its delay in taking 71 working days while reviewing its initial refusal of my request. And his judgment reveals that he had to serve a formal information notice on the Cabinet Office to obtain access to the withheld material so that his staff could assess it.

Twisted

The Commissioner also ruled that a "small section" of the requested information should be released.

This could lead one to believe that this material, such as it is and whatever it consists of, is already sufficiently encumbered by twisted grammatical constructions, completely unnecessary detail, pointless and futile repetition, not to mention rambling irrelevancies, and indeed quite possibly a wide variety of other attributes which tend to seriously undermine, if not altogether destroy, the clarity of reading matter and thereby also tend to boost the verbosity rating (perhaps measured on a scale of 1 to 10) of an official briefing paper, that it is deemed by the relevant authorities in this case to be fully suitable for public consumption already, without the otherwise necessary addition of any further clauses or sub-clauses or additional pointless repetition to prevent it from possessing the undesirable status of being regarded as excessively succinct and focused.

But I don't know that for sure, since the commissioner's reasoning for ordering the publication of this information is only laid out in a confidential annex to his decision. The government has 35 days to comply.

Meanwhile I am left perplexed by the notion that Cabinet Office civil servants who are perfectly capable of writing succinct and focussed briefings would apparently prefer to be perceived publicly as if they were part of a Dickensian Circumlocution Office, external.