UK floods: A question of competence?

- Published

As if the sound of torrential rain, rushing water and flooded homes wasn't grim enough, the story of the weather has also been one of blasts of political white noise from Westminster.

But it didn't start like this.

A matter of a few days ago, some politicians were openly reluctant to be seen taking an active interest on the ground, for fear of not just getting in the way, but irritating victims.

Being flooded out was bad enough, the logic went, without having politicians wandering around too.

Fast forward a few days, and politicians are everywhere, in their wellies on the telly.

Deputy PM Nick Clegg was out in Somerset on Monday

For the first time in almost a year, the prime minister held a big set-piece news conference in Downing Street, clearly determined to emphasise the government was now acting quickly, after criticism its initial response had been too slow.

And cameras were allowed in at the beginning of a special Downing Street floods meeting chaired by Mr Cameron on Wednesday morning.

At the press conference there was no end of quotes to leave the impression he was in charge and he understood the magnitude of events.

It might sound like a boring line from his diary, but the prime minister announced his planned trip next week to the Middle East was being called off.

He has clearly remembered the lesson from 2007 of being in the wrong place, out of the country, while there is flooding at home.

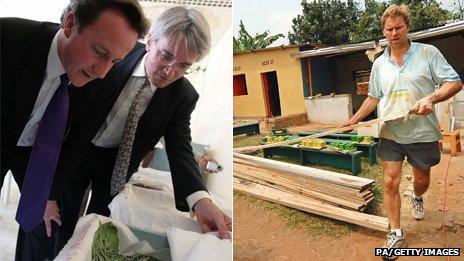

He was criticised then, as leader of the opposition, for a trip to Rwanda whilst parts of his Oxfordshire constituency of Witney were under water.

Mr Cameron and colleagues inspected silk worms and renovated an orphanage

But step back a little, and the last few days have been an insight into the raw politics of crisis management.

The central question has been who, or what is to blame?

Crudely, was it (a) winter, (b) the Environment Agency, (c) climate change or (d) politicians? Or some complicated combination of all four?

Clearly winter can be blamed. It has been the wettest for 250 years.

But over the weekend, as the blame game seemed to be heading towards cuts in flood spending, one man suddenly found himself the target: the chairman of the Environment Agency, Lord Smith, who used to be a Labour cabinet minister.

Owen Paterson had a hostile reception in the Somerset levels in January

"It appears that we need to dredge these two rivers," Mr Paterson agreed

Standing in for Environment Secretary Owen Paterson, who is recovering from an operation, Communities Secretary Eric Pickles apologised for the flooding and caustically observed: "We thought we were dealing with experts."

While Mr Pickles went further than any other minister in his criticisms of the agency, plenty of others refused to endorse Lord Smith, who is due to stand down in a few months anyway.

The job, incidentally, commands a salary of £60,632 a year, external for two to three days' work a week.

"Alongside excellent ambassadorial skills, you'll also be a team player able to build effective collaborative partnerships that deliver shared goals," reads the job advert.

The criticism of the leadership of the agency was beginning to dominate news coverage on the politics of flooding, but only until Lord Smith, well used to the political games of Westminster, decided to have a say himself.

Mr Pickles is standing in for Mr Paterson, who was suffering from a detached retina

Eric Pickles' remarks angered him as his staff know "100 times more" than any politician about flooding, he told BBC Radio 4's Today Programme.

But then he twisted the political knife.

BBC environment analyst Roger Harrabin had already reported that Environment Secretary Owen Paterson, off work recovering from an eye operation, was furious at Mr Pickles' tone.

A divide at the top of government was emerging, and Lord Smith knew how to open it a little further.

"I have indeed spoken with Owen Paterson by text. He has been hugely supportive throughout of the Environment Agency, its staff and its work and I very much appreciate that and I have passed that message on to our staff," he said.

Environment Agency boss Lord Smith is a wily Westminster operator

Perhaps aware the white noise of disagreement would look not only undignified but irrelevant to those flooded out, the government's strategy immediately changed.

Yes, implicit swipes at the Environment Agency's management continued, but the explicit message was one of collaboration.

Hard hat and fluorescent jacket on, it was the prime minister's repeated refrain during his two-day trip to the south west of England.

The question of blame won't go away. Neither will the government's desire to ensure it doesn't unfairly take too much of it.

But David Cameron is now aware of the scale of what has happened - and he predicts will continue to happen - and knows the reaction to it will be seen as an issue of his competence.

There is no attribute any prime minister cherishes more, particularly just over a year from a general election.

This is far from just a challenge, and potential opportunity, for the prime minister.

As opposition leader, Ed Miliband can offer sympathy but not action

For Labour and Ed Miliband, the task is being seen to be relevant.

A big speech on reforming public services he made on Monday evening received little attention.

And his own trip to see the impact of the floods in Purley in Berkshire always ran the risk of looking impotent. Getting involved in political rows as homes flood is a high risk strategy, so sympathy is mostly what oppositions can offer.

For the prime minister, despite holding the levers of power, getting things done can sometimes be a challenge. The main political danger is looking like you're not in control.

But the political rewards of getting it right can be huge - as shown when Gordon Brown was judged to have had a good flood in 2007, confounding sceptics with a popularity boom in his first few weeks as prime minister.