Did Blue Arrow make bank fraud untriable?

- Published

Blue Arrow Clip

The City has been no stranger to financial scandals over the past two decades - but some think there have been too few prosecutions. Can the reason be traced back to one trial in 1992?

The Blue Arrow case went down in history as Britain's most expensive criminal trial, costing an estimated £40m (roughly £70m adjusting for inflation).

A year-long trial, which began in February 1991 at a purpose-built court off Chancery Lane, resulted in the conviction of four high profile bankers - but the prosecution's joy turned out to be short-lived.

The convictions were overturned a few months later when the Appeal Court ruled that due to the length of the trial and the complexity of the subject matter the jury could not have reached a fair verdict.

It was labelled a "costly disaster" that must never be repeated, by Appeal Court judge Lord Justice Mann.

Some believe this ruling led to the Serious Fraud Office deciding to never again pursue a similar prosecution of a big City institution or its senior executives - that it views some cases as being so complex that they are simply "untriable".

"The truth of the matter is [the SFO] are frightened to take these cases on," says Rowan Bosworth-Davies, a financial crime consultant and former Scotland Yard detective.

"If Blue Arrow had any impact it was that the SFO knew they were never going to get close to the City establishment ever again."

Lord Phillips of Sudbury, a legal expert and Liberal Democrat peer, says the Blue Arrow affair has remained in the "institutional memory of the prosecutorial authorities and regulators".

David Green, the current director of the Serious Fraud Office, admits the watchdog may have held back from pursuing convictions over fears the trials might collapse.

But he adds: "That might have been the case on occasions in the past, but it isn't now."

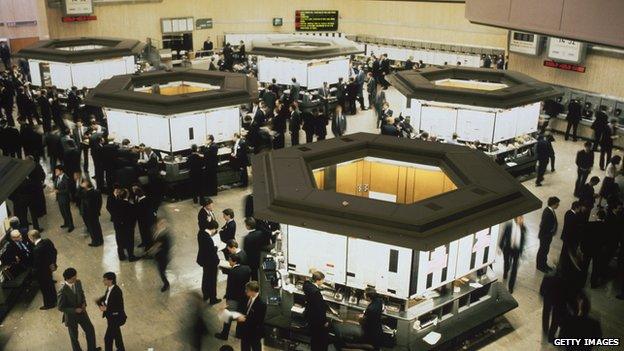

In the mid-1980s a roaring bull-market was being fuelled by a boom in mergers and acquisitions. Banks were earning large profits from aiding companies take each other over in a bid to build larger and more profitable organisations.

London Stock Exchange boomed in the mid-1980s, with huge deals being done

Deals were being closed, using the concept of 'leverage' - buying assets with borrowed funds - and it seemed that virtually anything was possible.

At the height of this boom an upwardly mobile employment company, Blue Arrow Ltd, made a bid to take over the world's largest recruitment agency Manpower.

To finance this, Blue Arrow launched a record-breaking £837m rights issue, offering existing shareholders the right to buy additional shares in the company.

Few of the new shares were wanted by Blue Arrow's shareholders so County NatWest, the now defunct investment banking arm of NatWest, and stockbrokers UBS Philips and Drew were tasked with finding buyers for the left over shares - roughly 51% of the new issue worth around £472m.

They were only able to find buyers for roughly half of this and hid a remaining 19% stake in Blue Arrow in subsidiary companies in order to allow the takeover of Manpower and protect their reputations.

Spreading their stake throughout the subsidiaries meant the banks avoided Section 209 of the Companies Act which requires all holdings over 5% to be disclosed to the Stock Exchange.

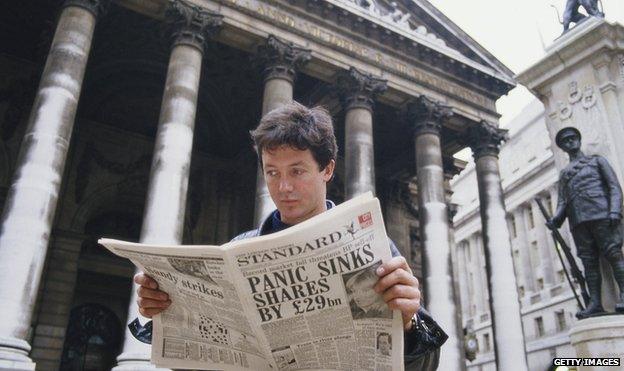

The plan was to dribble the excess stock back on to the market over a period of months and had it not been for the stock market crash of October 19, 1987, the plan may have worked.

A man reads about the stock market fall in London in 1987

In hiding the stocks County had become hopelessly exposed and incurred huge losses during the crash. County NatWest, which was left with a £157m stake in Blue Arrow's shares, was to see £87m wiped off its holding.

Eleven executives in total from County and UBS Philips and Drew were arrested and charged by the Serious Fraud Office for their part in the scandal. The 11 were whittled down to five, four of whom were convicted after a 13-month trial.

Jonathan Cohen, David Reed, and Nicholas Wells, all senior executives of County NatWest, were given 18-month suspended prison sentences after being convicted of misleading financial markets.

A fourth, Martin Gibbs, a stockbroker and former director of UBS Phillips and Drew, was given a 12-month suspended sentence for his part in the conspiracy. All the convictions were overturned on appeal.

The Blue Arrow case was one of a group of corporate bank fraud cases that were being heard at the time. Two years earlier the Guinness share trading fraud trial saw four men jailed for trying to artificially raise the share price of the brewing giant during the 1986 takeover of Distillers.

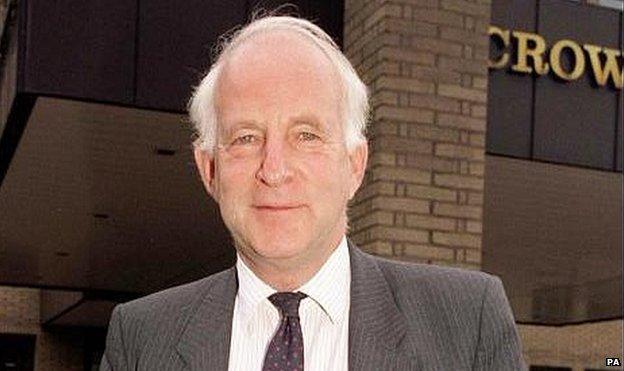

Former Guinness chief executive Ernest Saunders was convicted in 1990 with three others in 1990 for his part in a conspiracy to drive up the price of Guinness shares during the takeover of drinks giant Distillers

Since then individuals such as Abbas Gokal - a shipping magnate sentenced to 14 years in prison in 1997 - have been given jail terms for their roles in bank frauds but no wide scale bank frauds have resulted in bankers being jailed.

It is a situation Lord Phillips believes is "deeply damaging" the country: "It's a scandal that not one director from the board of a mainstream bank has gone to jail."

Other Serious Fraud Office directors may have taken a more "civil" approach to prosecuting bank fraud, doling out fines rather than securing convictions, but Mr Green maintains he is committed to using his position to pursue criminal charges against "the very top most level, of really serious fraud, bribery and corruption".

The Serious Fraud Office is currently investigating Barclays, Rolls-Royce and the Libor rate fixing scandal - an example, says Mr Green, that it is not scared to take on big City institutions.

"I've got well over 60 people working on [the Libor investigation] using additional 'blockbuster funding' from the Treasury to help cover costs and we've charged a number of people.

David Green says the court system has improved since 1992

"Are we willing to take tough cases on anymore? The answer is very much so, yes," Mr Green says, adding: "We have 14 trials of 44 defendants awaiting trial."

The ability of lay juries to understand serious fraud trials has been a subject for debate since a 1986 report, by Lord Roskill, advocated abolishing juries in complex fraud trials to make the process more "expeditious".

But for the time being this view has fallen out of favour.

"This idea that ordinary juries can't understand, is the first mistake that all these clever people make. But actually the truth is [they] understand only too well " says Mr Bosworth Davies.

"That's why juries are so good are dealing with dishonesty cases, because they get it."

A view both Lord Phillips and Mr Green agree with.

"The facts might be quite complicated, that tends not to bother a jury normally," says Mr Green.

"Very often these cases will come down to a very simple question - whether or not certain conduct was dishonest, and you know what dishonesty is, and so do I."

Institutional problems still remain though, according to some.

The SFO is trying to repair the damage done to its reputation following the collapse of many of its key cases due to mismanagement and the revelation that it had lost thousands of documents relating to its investigation into BAE systems.

In March this year the SFO was blamed for the collapse of a bribery trial against Victor Dahdaleh, businessman and Labour party donor, after the SFO's key witness changed evidence and it was revealed that one of the SFO's lawyers had delegated parts of its investigations to a US law firm.

While in 2012 investigations into the flamboyant property developing Tchenguiz brothers, who are currently in the process of suing the SFO, were dropped after being labelled "sheer incompetence" by a senior High Court judge.

"There is an utter failure of our prosecutorial authorities to implement the laws that lie on the statute book," says Lord Phillips, a problem he attributes to the SFO being "criminally understaffed".

"The SFO and HM Revenues and Customs are good people but can't get near the big boys. It's David without his sling against Goliath."

Pool of jurors

Mr Bosworth-Davies, who was previously head of enforcement at the Financial Intermediaries, Managers and Brokers Regulatory Association (FIMBRA) - now part of the Financial Conduct Authority - believes there is a wider problem.

"It's all to do with class. The people who you're going up against are the people from the upper socio economic echelon."

Invoking the spirit of Edwin Sutherland, the American sociologist that coined the term "White Collar crime", he says: "Society has a difficulty in treating these people as criminals and there is a consistent bias in applying criminal justice under laws that apply to business and the professions."

Mr Green admits that all of the SFO's cases are high risk as "the other side is always very well lawyered up and very well supplied".

He is, however, optimistic about the prospect of securing convictions, pointing to improvements in the court system since the days of Blue Arrow.

Judges now take a more active role on the management of trials - and the pool of potential jurors has been widened.

Despite the many difficulties posed by complex fraud cases, Mr Green argues that changes in the legal process would at least "allow us to manage a trial of the Blue Arrow scale these days".