Heath, Thorpe and the lost coalition of 1974

- Published

Edward Heath and Jeremy Thorpe were keen to form a coalition in 1974, their parties less so

Forty years ago today Harold Wilson returned to power as Labour Prime Minister. But it could have all been different if Conservative Ted Heath and Liberal Jeremy Thorpe had succeeded in their coalition talks.

Voters had gone to the polls to give their answer to a stirring challenge from a Conservative prime minister: Who Governs Britain?

That was the battle cry of Ted Heath. His government was in the grip of an energy crisis, and facing a crippling strike by the miners and other key workers.

Oil prices were rocketing. Industry was restricted to working a three-day week to save power. TV channels shut down early. Children did their homework by candlelight.

The energy minister, Patrick - now Lord - Jenkin, suggested novel ways to save electricity, even urging people to brush their teeth in the dark.

The National Union of Mineworkers had provoked a major government crisis.

'Razor's edge'

Lord Carrington, the Conservative Party chairman at the time, recalls: "We would have run out of coal by the beginning of March... no hospitals, no lights... it would have been an impossible situation."

Mr Heath called a snap election, and went on national television with a stark message for the British people: "It is time for you to say to the extremists, the militants, and to the plain and simple misguided... we have had enough."

The Conservatives began the election campaign well ahead but the gap began to narrow as the Liberals, led by the charismatic Jeremy Thorpe - a latter-day Edwardian dandy in his trademark three-piece suit and jaunty trilby hat - picked up votes from disillusioned Tory supporters.

By the time the polls closed, experts were predicting a "razor's edge" election and, as the final results straggled in the next morning, the country was waking up to a new political landscape - a hung parliament, with no party having enough MPs to vote down all its opponents in the new House of Commons.

Nothing like this had happened since 1929 and, with mutterings about a constitutional crisis, the Queen cut short a state visit to Australia and flew home.

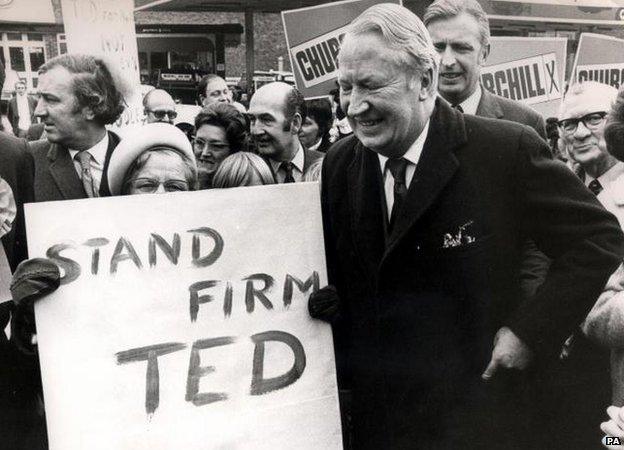

Edward Heath thought his opposition to the miners would win over voters

But not everyone was keen on the Conservative leader staying on in Downing Street

Labour's leader, wily former Prime Minister Harold Wilson, had laid elaborate plans to slink away quietly, evading the press and media, if, as he expected, the Tories had won.

But Wilson was wrong.

The voters' dusty answer to Mr Heath's defiant challenge "Who Governs Britain?" was clear enough: "Not you". However, they seemed less sure whom they wanted instead.

Labour had the most seats - four more than the Conservatives - but Heath's Tories had won more votes overall, and neither had a majority in Parliament so could be defeated if all their political rivals combined together.

The Liberal Party had its best election result since the 1930s - winning six million votes, almost one in five of the electorate and establishing a beach-head, in terms of its vote share, from which the party and its successor, the Liberal Democrats, have rarely had to retreat.

But the vagaries of Britain's first-past-the-post electoral system translated those votes into just 14 MPs, not the 120 it might have had under a proportional voting system.

Liberal leader Jeremy Thorpe was outraged, commenting: "I think there will be millions of angry people who will feel they have been cheated of parliamentary representation by an iniquitous electoral system."

With no clear election winner for the first time since the 1920s, Heath decided not to resign straight away but to stay on in Downing Street and invite the Liberal leader in for urgent talks on forming a possible coalition. Sounds familiar!

Many Tory MPs and activists were appalled at the prospect, and said so. And they were not the only ones. Most Liberal parliamentary candidates were outraged too.

One of them was a young Scottish lawyer, Menzies Campbell, now Sir Menzies - a Lib Dem grandee and former party leader. He says there was a "peasants' revolt" by the party's candidates.

Jeremy Thorpe was an electoral success for the Liberals in 1974

"I have no doubt that Jeremy Thorpe harboured ambitions of getting into government but we had spent the past three or four weeks knocking and attacking the Tories, so we didn't think it was a good idea for him to march into Downing Street.

"A lot of the foot soldiers were ringing the party's high command saying under no circumstances should this go any further."

But it did go quite a lot further.

A secret memo about that extraordinary weekend, written by Heath's private secretary at the time, Robert - now Lord - Armstrong, reveals how he helped smuggle Thorpe into Number 10 on the Saturday afternoon after the election, avoiding most of the waiting journalists, TV cameras and protesters.

'Don't you dare'

Thorpe then regaled a bemused Heath, and his private secretary, with how he had eluded the press as he set off from his North Devon constituency: "He had sent his car, with a bag, to a neighbouring farm to await him.

"Then he had donned a country coat and Wellington boots over his town suit, walked across three wet fields to the farm, and driven from there to Taunton, where he caught the train to London."

But Thorpe was cautious in his talks with Heath and, knowing the strong feelings in his party against any deal with the Tories, he had kept some of his closest colleagues in the dark.

His right-hand man, the party's chief whip at the time, was David - now Lord - Steel, who would later lead the Liberals himself.

When he belatedly found out about the talks, Steel headed for London, from his home in the Scottish borders, with the warning of a key local Liberal ringing in his ears: "Don't you dare come back as a minister in Ted Heath's government."

Heath and Thorpe held a series of talks at Downing Street and by telephone.

Harold Wilson kept his counsel and ultimately returned to Number 10

The Liberals were offered a coalition with a cabinet seat for their leader but only a Speaker's Conference - a talking shop - on their political holy grail: electoral reform.

It was a very tense few days inside Number 10, "a horrible time", as Lord Carrington recalls.

Throughout these coalition talks the Labour leader, Harold Wilson - beaten by Heath in 1970 - kept his head down, during what he famously called "that longest dirty weekend".

But he was not totally in the dark over what was going on.

One of his advisers, Bernard - now Lord - Donoughue, has revealed he was getting inside information from a senior Liberal Party source: "I had a friend at the top of the Liberal Party who I was phoning every few hours and who was reassuring me that the Liberals would not join with the Conservatives... even though Jeremy Thorpe was, in his words, very keen to get his knees under the cabinet table.

"He said the party's grassroots, especially in the West Country, would not have it."

The constitutional role of the Queen in these unusual circumstances was what was worrying some of the most senior political mandarins and Palace advisers.

But the agreed view was that the sovereign had nothing to do as long as she had a prime minister - the rest of it was not her problem.

Not that anyone could be really sure. Britain's unwritten constitution remained shrouded in mystery.

Jeremy Thorpe and Edward Heath campaigned together to keep Britain in Europe in 1975

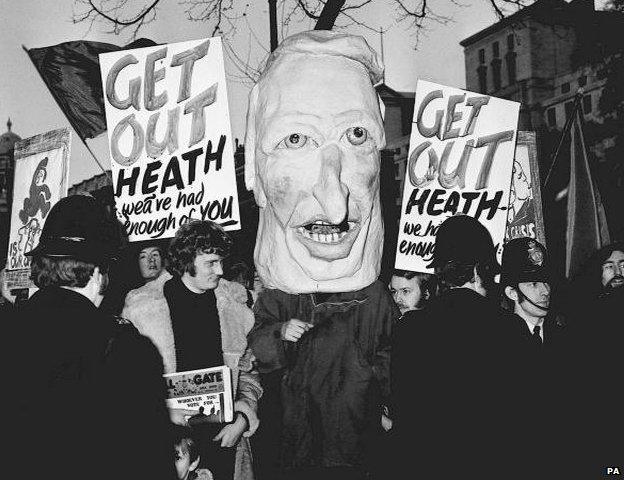

But, fortunately for the Palace perhaps, many Liberals feared a coalition would see their party swallowed up by the Tories and the talks with Heath finally collapsed on the Monday after the election, as a crowd outside Number 10 chanted: "Heath must go."

The experience scarred the defeated prime minister who turned to his friend and party chairman, Lord Carrington, in bewilderment, asking him: "Why do people hate me so much?"

Lord Armstrong recalls how he alerted Buckingham Palace that the prime minister would be coming to tender his resignation, but he felt he had one last duty to perform as Heath's private secretary.

"Because Mr Heath was a bachelor and at that point a very lonely man, I thought somebody must go with him in the car to the Palace. He was very downcast."

And it was a journey that Lord Armstrong recalled in that secret, often poignant, Downing Street memo, now in the public domain: "At 6.25pm the prime minister left Downing Street for Buckingham Palace. I went with him; and on the drive we neither of us said a word. There was so much, or nothing, left to say."

Harold Wilson returned to power, heading a minority Labour government.

In his autobiography years later, Heath defended his decision to hold talks with the Liberals, and could not resist a pointed dig at one of his former cabinet colleagues and bitterest rivals: "It was our duty to negotiate with the Liberals even if this might give ill-disposed people an opportunity to claim that we were trying to hang on to office.

The Queen's constitutional role was called into question

"Mrs Thatcher wrote in her memoirs that the horse-trading was making us look ridiculous. The alternative was to give up without a fight. She certainly did not advocate that at the time."

Thorpe later defended his actions too, saying: "The attitude I took, and the reaction I gave to Mr Heath's offer was that which I thought was right for the country and right for the Liberal Party."

But the failure of those coalition talks was not only down to tribalism in the Liberal and the Conservative parties.

Already, rumours were swirling around Westminster about Thorpe's private life.

Five years later, he would be acquitted, in a sensational trial, of conspiring to murder a former male model, Norman Scott, after allegations - strongly denied - of a homosexual affair.

Labour's Lord Donoughue has no doubts that this could have scuppered any deal with the Tories: "Thorpe was a landmine waiting to go off." He adds that it was a landmine Labour would have been willing to detonate.

Lord Armstrong says Downing Street was also aware of the rumours already circulating about the Liberal leader: "I think he thought of being home secretary in any coalition, but there was already enough known about his own personal problems for us to be aware that this could be very difficult."

Jeremy Thorpe was acquitted of conspiracy to murder in 1979

After the trial, Thorpe left politics and public life, becoming something of a lost leader of the Liberals, one who, supporters claim, has been virtually airbrushed from his party's history.

Yet he led the Liberals to their best election result for decades, a result which signalled the beginning of the end of the post-war, exclusive Labour/Conservative, Tweedle Dum/Tweedle Dee duopoly of power.

As Sir Menzies Campbell explains: "The scale of our success in that 1974 election, winning nearly 20% of the vote, took the Liberal Party by surprise. That was the election in which we cast aside the old music hall joke '... and the Liberal lost his deposit'. Thorpe was the leader who did that."

Thorpe has suffered for decades from Parkinson's Disease and has rarely been seen in public for the past 30 years. He will be 85 this year, and lives quietly in London with his second wife. He told me: "The February 1974 election was indeed a turning point - six million votes nationwide but only 14 seats.

"I quite agree that the record of that period should be historically registered but, in my state of advanced Parkinson's Disease, I do not feel able personally to take part in your project."

It is down to the voters to deal the electoral cards but, if next year's poll produces another hung parliament, will it be 1974 all over again - with a minority government because activists in the largest party and the Lib Dems want nothing to do with each other?

Or will the comfort and cuddliness of coalition with the Tories, or even misty-eyed memories of the Lib-Lab Pact in the 1970s, help Nick Clegg to avoid Jeremy Thorpe's mistake 40 years ago, and take his party with him as he tries, once again, to make common cause with either Conservatives or Labour?