Peel to prudence: 10 historic Budgets

- Published

Will Chancellor George Osborne's Budget on Wednesday go down in history? Here are some that have already done so, starting with Robert Peel establishing income tax in 1842:

Sir Robert was not the first PM to levy a tax on income - it was first introduced by William Pitt the Younger to help finance costly campaigns in the Napoleonic Wars, but was abandoned when peace returned.

In 1842, income tax was again touted as a temporary measure. PM Peel wanted both to combat the "mighty and growing evil" of the rising national debt and cut taxes, tariffs and excises to promote free trade.

"For a time to be limited" therefore, income above a certain threshold was to be taxed at a rate of seven old pence in the pound, or about 3%.

The temporary tax has evolved greatly since then, but has remained resolutely in place.

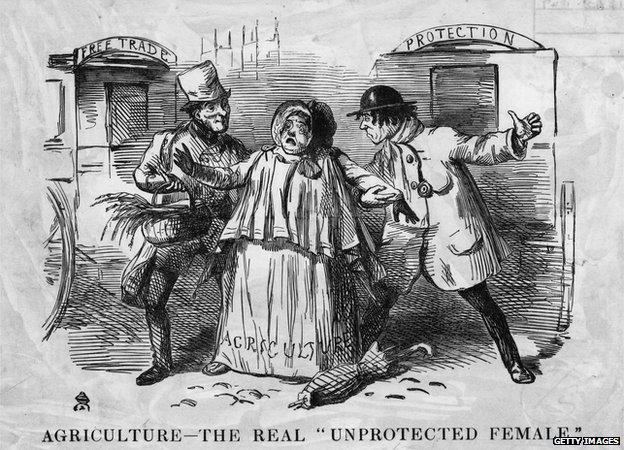

1852: Benjamin Disraeli attempts to placate free-traders

Benjamin Disraeli had bitterly opposed Sir Robert Peel's efforts to repeal the Corn Laws, which imposed punitive duties on foreign grain, earning a reputation for protectionist instincts.

This was caricatured in the above cartoon, which shows Disraeli in 1846 attempting to steer the "unprotected female" of agriculture into a carriage marked "protection".

Yet his 1852 Budget was designed to win the backing of free-traders by cutting taxes on malt and tea, thereby securing the survival of the Conservative minority government in which he served under Lord Derby.

It wasn't to be. Facing defeat both in the Commons and in the ensuing general election at the hands of a coalition of Whigs and Peelites, Disraeli wound up the debate declaring: "England does not love coalitions."

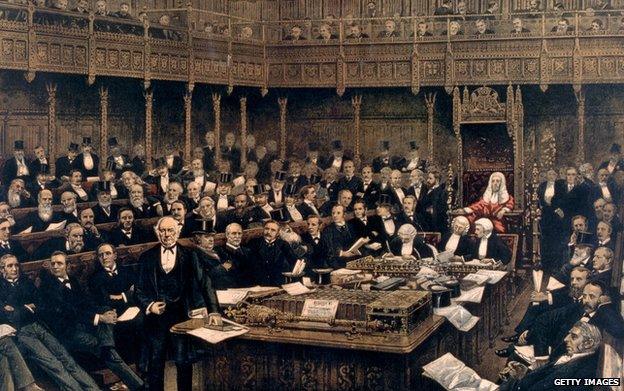

1853: William Gladstone delivers on free trade

The Liberal disciple of Peel and great rival of Disraeli, William Gladstone took over as chancellor when it was decided coalitions weren't so bad after all.

His first ever Budget statement, in April 1853, lasted well over four hours. Despite its length, it was held to be an oratorical triumph.

It abolished duties on 123 items, including tea, and cut duties on 133 others. Income tax was extended to compensate for the exchequer's lost income.

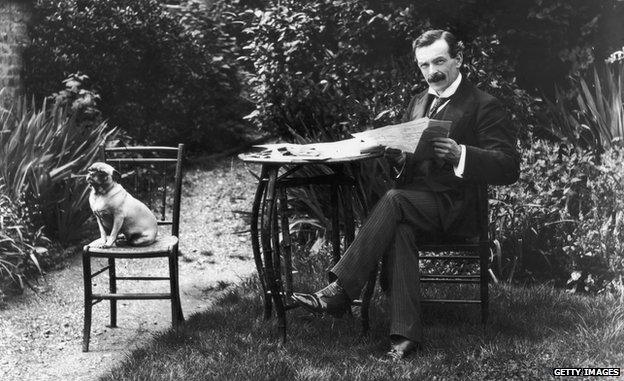

1909: David Lloyd George takes on the landed gentry

Future Liberal PM David Lloyd George branded his 1909 effort the "people's Budget".

It provided for social insurance that was to be partly financed by land and income taxes.

During a marathon four-and-a-half hour speech, he demanded: "Is it too much, is it unfair, is it inequitable, that Parliament should demand a special contribution from these fortunate [land] owners towards the defence of the country and the social needs of the unfortunate in the community, whose efforts have so materially contributed to the opulence which they are enjoying?"

The House of Lords evidently thought it was, and rejected the Budget.

This prompted Lloyd George to drive through a great constitutional overhaul: the Parliament Act of 1911, which stripped the upper chamber of its ultimate power of veto on financial matters.

1925: Winston Churchill revives the gold standard

Winston Churchill's Budget of 1925 has become infamous for returning Britain to the gold standard, at a fixed rate of $4.80 to the pound.

The aim was to restore Britain's position at the centre of the world's financial system.

But it was later accepted that the high rate made British industry uncompetitive and prolonged the slump.

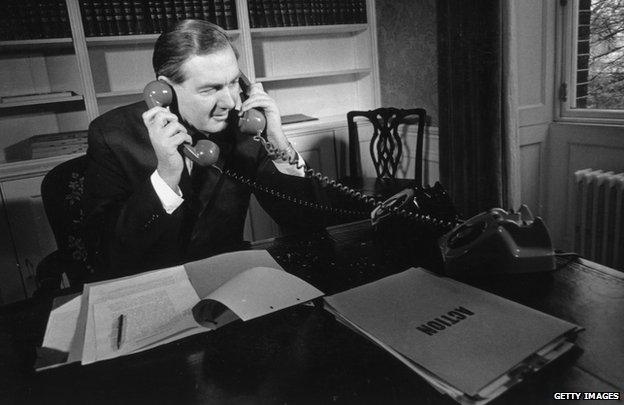

1964: Jim Callaghan broadens tax base

The Conservatives had introduced a "speculative gains tax" earlier in the decade, but when Labour regained power in 1964 Chancellor Jim Callaghan created a new capital gains tax which was to be set at a flat rate of 30%.

This would apply not just to shares sold within six months or land sold within three years of acquisition, but to longer-term capital gains.

"This measure will bring to an end the state of affairs in which hard work and great energy are fully taxed while the fruits of speculation and passive ownership escape untaxed," he declared.

The Budget statement, delivered on 11 November 1964, also unveiled a new corporation tax, which remains with us to this day.

Both fiscal innovations were enacted the following year.

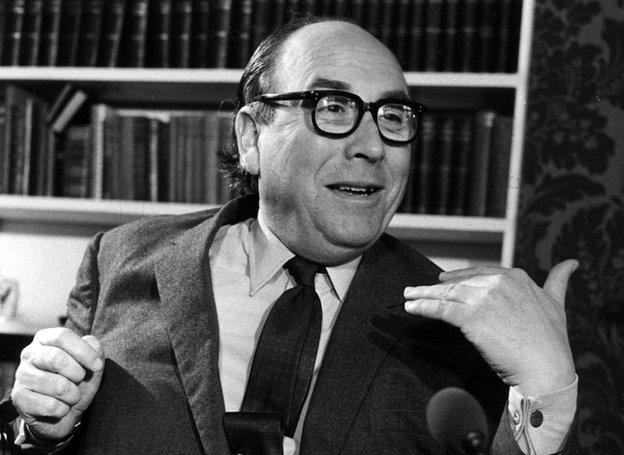

1968: Roy Jenkins substantially increases taxation

Having been forced to devalue sterling in November 1967, PM Harold Wilson appointed Roy Jenkins to be Callaghan's successor as chancellor.

His first Budget brought in large increase in indirect taxation as he declared that the country would have to go through two years of "hard slog".

1981: Geoffrey Howe resolute on Thatcherite economics

Inflation was soaring, even though the government had staked its credibility on taming it, and 364 economists wrote to The Times, claiming that monetarist policies had no basis in economic theory, would deepen the recession and should be abandoned.

But Chancellor Geoffrey Howe declared in the 1981 Budget that "to change course now would be disastrous".

1993: Norman Lamont sets sights on recovery

Concerned by the burgeoning deficit, Chancellor Norman Lamont (pictured above with his special adviser David Cameron) set out plans to substantially raise revenues in successive years after 1993.

VAT was phased in on domestic gas and electricity bills and taxes on cigarettes, petrol and beer were all increased by more than the rate of inflation.

"I have demonstrated clearly how we will bring government borrowing down in the years ahead," the chancellor told MPs.

"That is the only way to sustain growth and build a strong and sound economy in the 1990s."

1997: Gordon Brown espouses prudence

Delivering the first Budget after the end of Labour's 18 years in opposition, Chancellor Gordon Brown told MPs he had identified the UK's four key economic problems as "instability, under-investment, unemployment, and waste of talent".

Stability, he claimed, could be delivered in part by the "golden rule", that "over the economic cycle the government will borrow only to invest, and that current spending will be met from taxation". Brown used the word "prudent" six times in the speech.