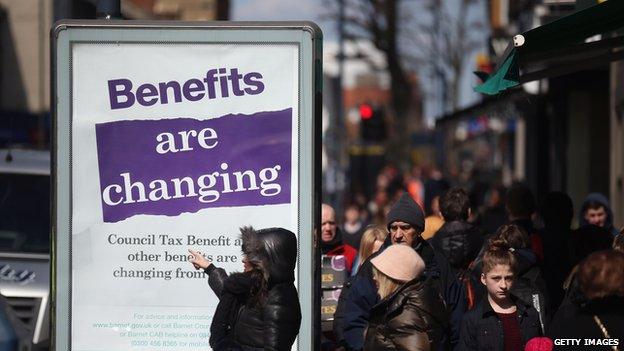

The welfare state: Charity that wounds?

- Published

Could too much compassion in the welfare state hurt the very people it is supposed to help?

Ed Miliband suggests that might be the case.

In a recent speech he drew on the ideas of a sociologist - Richard Sennett - who said compassion had the power to wound.

One of the Labour leader's closest aides - the shadow minister Lord Wood - says that Sennett has made a "deep impression" on Miliband.

If the language sounds a bit academic, the reaction to Sennett's theory at a South London woman's group called Skills Network is anything but.

In a couple of rooms beside a railway line, women gather for training, moral support and shared childcare.

Many are single parents, some do not have permanent homes.

Most rely on the state. None trusts it.

"We are patronised by all these people that are supposed to be there for us," says Onley.

"Anyone of official status comes to visit a family you're almost on edge, even down to midwives after you've had a baby," adds Hannah.

They are not merely sceptical of the state's professionals, they see them as a threat.

One mother explains her experience of being visited by social workers.

"They always have a tick register in their purse and they take it out," she says. "All these things are useless. Nothing is changing my life. In fact they're wasting my time and their time."

The feeling for some is not of disenchantment, but outright hostility.

Onley says: "Because you're given something does that mean we should just lie there and take whatever you give us and don't argue about anything or ask any questions?

"People need to be treated as equal human beings."

Sennett blames that attitude on the way the state works. He has written: "Charity itself has the power to wound; pity can beget contempt; compassion can be intimately linked to inequality."

In an interview for BBC Radio 4's the World at One programme, Wood says Labour is interested in the idea that inequality is partly about the gap in respect and power between the state, and people on the receiving end of its services and benefits.

In embracing some of Sennett's thinking, Wood suggests Miliband intends to do things differently from the way previous Labour administrations have behaved.

"Here's the difference with maybe Labour parties of before," he says. "In addressing inequality you can't just have a central state that adds up the ledger of who is doing well and who is doing not and just sort of reshuffle money around and ask people to fit certain categories that the government's devised.

"You've got to think about shifting power back down as well as thinking about inequality in a deeper sense."

That sounds a little like the critique of Gordon Brown's attempts to deal with child poverty: that he was merely redistributing money to nudge people over a statistical line so they were no longer classed as impoverished.

Wood - who worked for Brown - does not repeat that criticism.

Pressed for examples of how his concerns translate into policy he highlights plans to hand control of parts of the work programme to some towns and cities and ideas about giving people more of a voice about where housing is built and how it's allocated.

He argues that responsibility for policy needs to change so people affected by decisions feel they have a say.

Labour's opponents will say that this is vague stuff.

The government argues it already understands the problem.

Ministers say they are changing the culture for benefit claimants, making their responsibilities clearer, and giving social housing tenants control of their own housing benefit.

Others will simply reflect that a focus on getting people off benefits and into jobs would sidestep many of these issues. With public money tight, officials would need to think carefully before skimping on the scrutiny they apply to the way funds are spent.

Will Labour leader Ed Miliband implement Sennett's ideas if he becomes prime minister?

Sennett is - unsurprisingly - pleased that Miliband embraces his thinking, but he doesn't easily fit the mould of a "Miliband guru".

He votes for the Green party and describes Miliband as "not a particularly charismatic politician" who may never have the chance to implement his idea.

And if Miliband does want to reshape Britain's relationship with its welfare state, it won't be easy.

In South London Hannah reflects on her encounters with its professionals.

"It's almost like having the crocodile smile," she says.

"You see all the smiley teeth and you're waiting for the bite to come and get you."