2019 European Elections: How does the voting system work?

- Published

Seats in the European Parliament representing England, Scotland and Wales are distributed according to the D'Hondt system, a type of proportional representation.

The nations are divided into 11 electoral regions: nine in England, plus Scotland and Wales. For this election, Gibraltar votes as part of a combined constituency with the south-west of England.

Parties vying for election submit a list of candidates to voters in each region.

A system devised by Victor D'Hondt, a Belgian lawyer and mathematician active in the 19th Century, dictates the results:

In the first round of counting the party with the most votes wins a seat for the candidate at the top of its list

In the second round the winning party's vote is divided by two, and whichever party comes out on top in the re-ordered results wins a seat for their top candidate

The process repeats itself, with the original vote of the winning party in each round being divided by one plus their running total of MEPs, until all the seats for the region have been taken

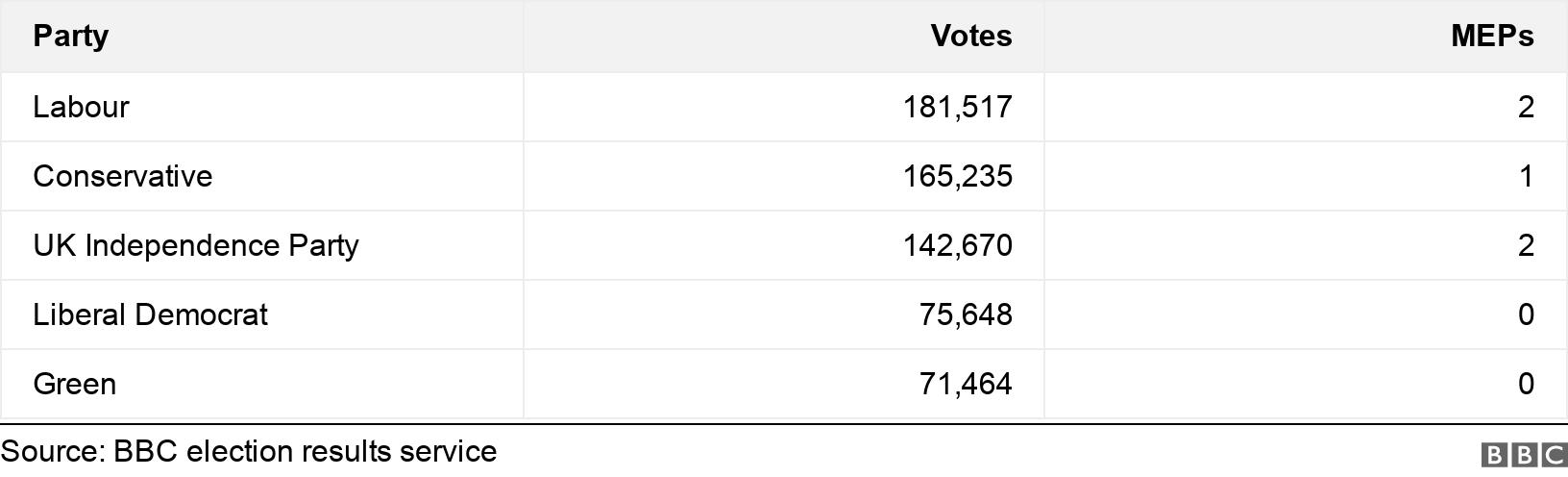

By way of example, here are the results for one region of England, the West Midlands, in 2014, which had a total of seven seats in the European Parliament up for grabs. For simplicity's sake, only the five largest parties by vote share are included:

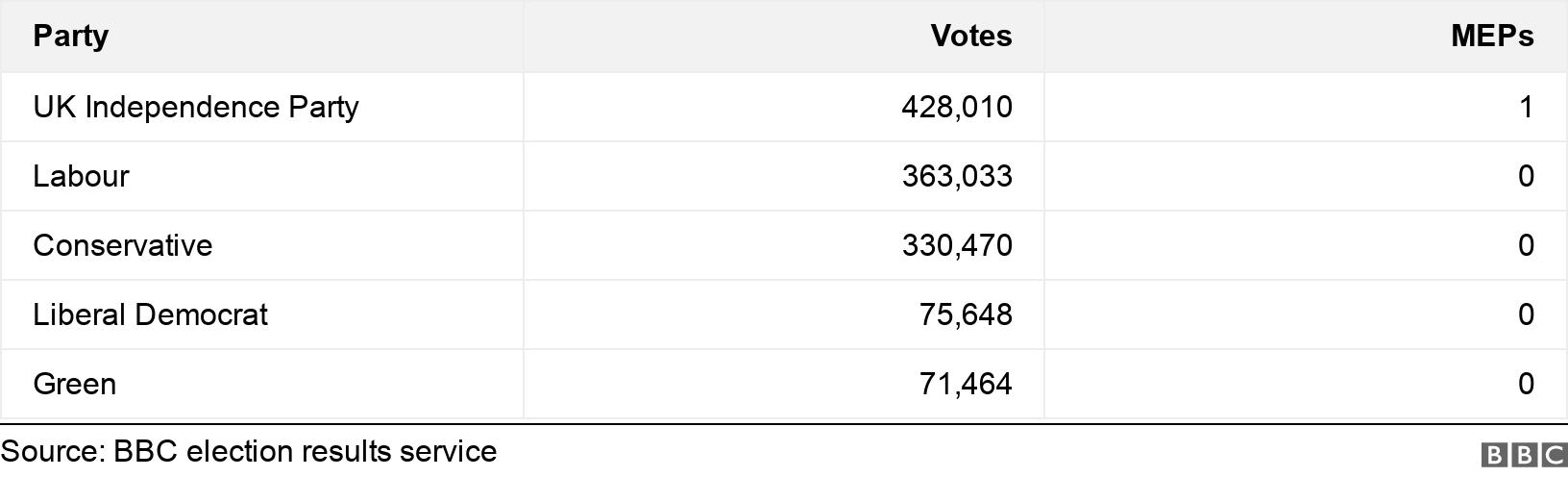

Round one

UKIP wins the largest number of votes and the candidate at the top of their list is elected.

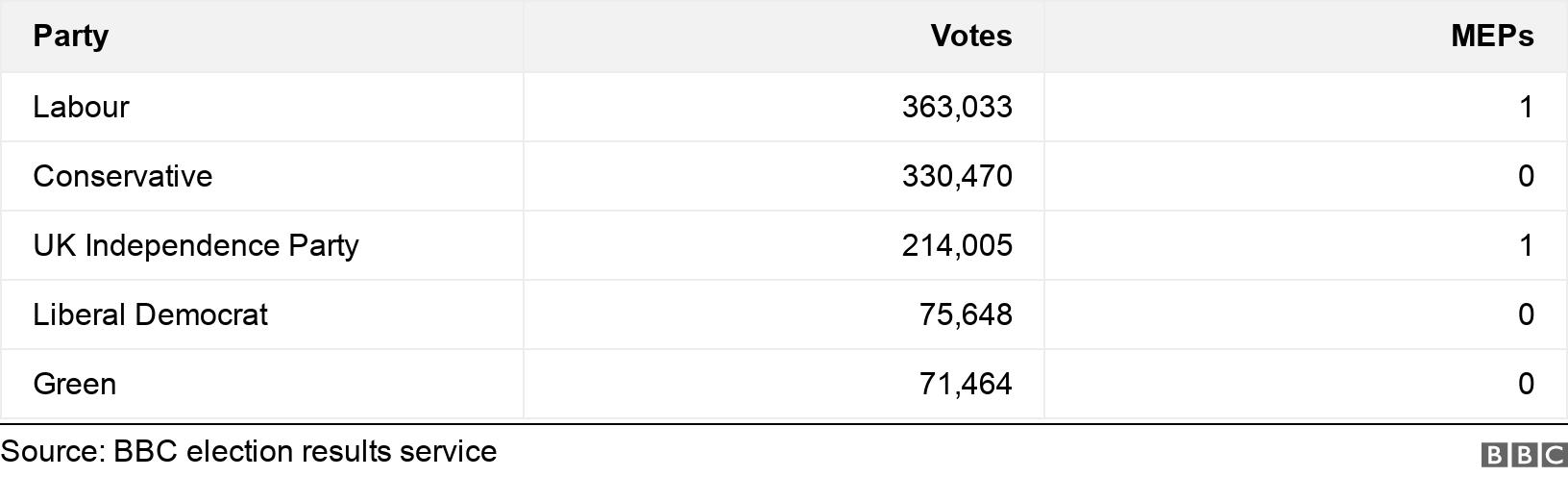

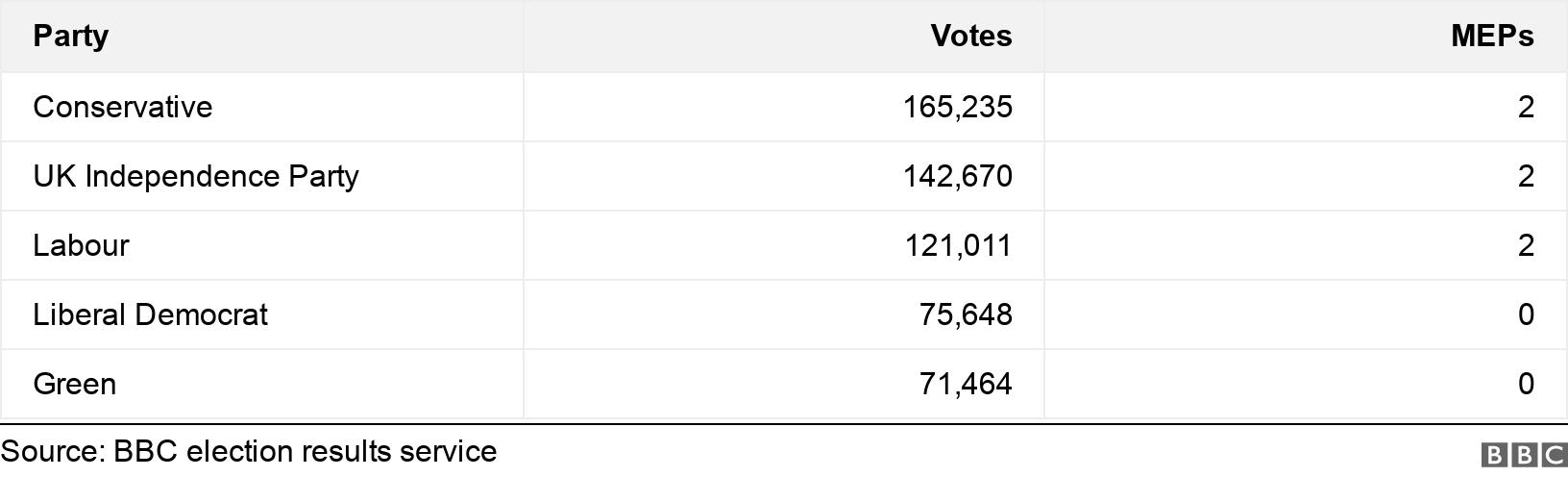

Round two

As UKIP already has one candidate elected, its vote is divided by two (one, plus the number of MEPs it has). Now, Labour comes out on top and the candidate at the top of its list of candidates is elected.

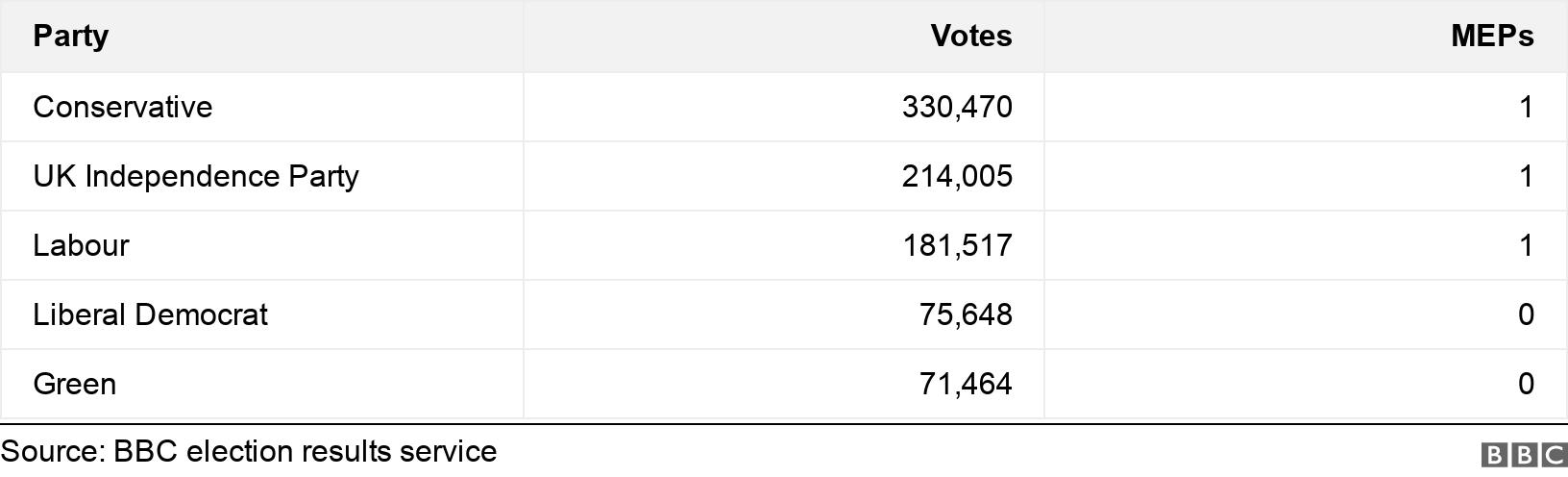

Round three

After Labour's vote is divided by two (one plus the number of MEPs it has), the Conservative Party wins and its top candidate for the region is also elected.

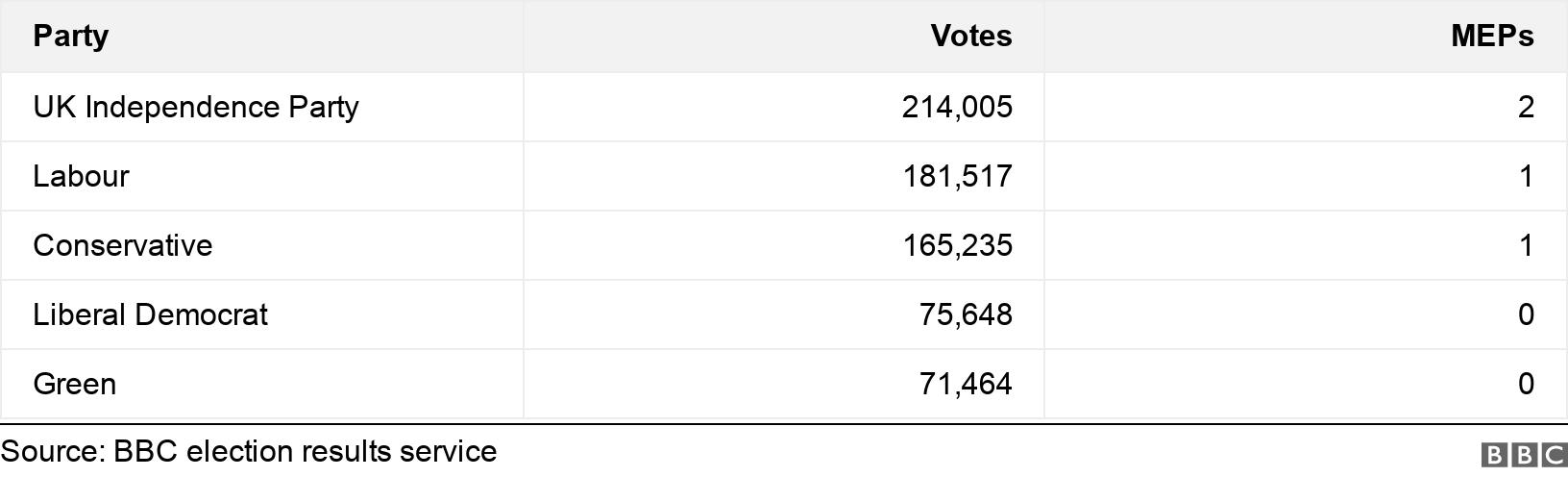

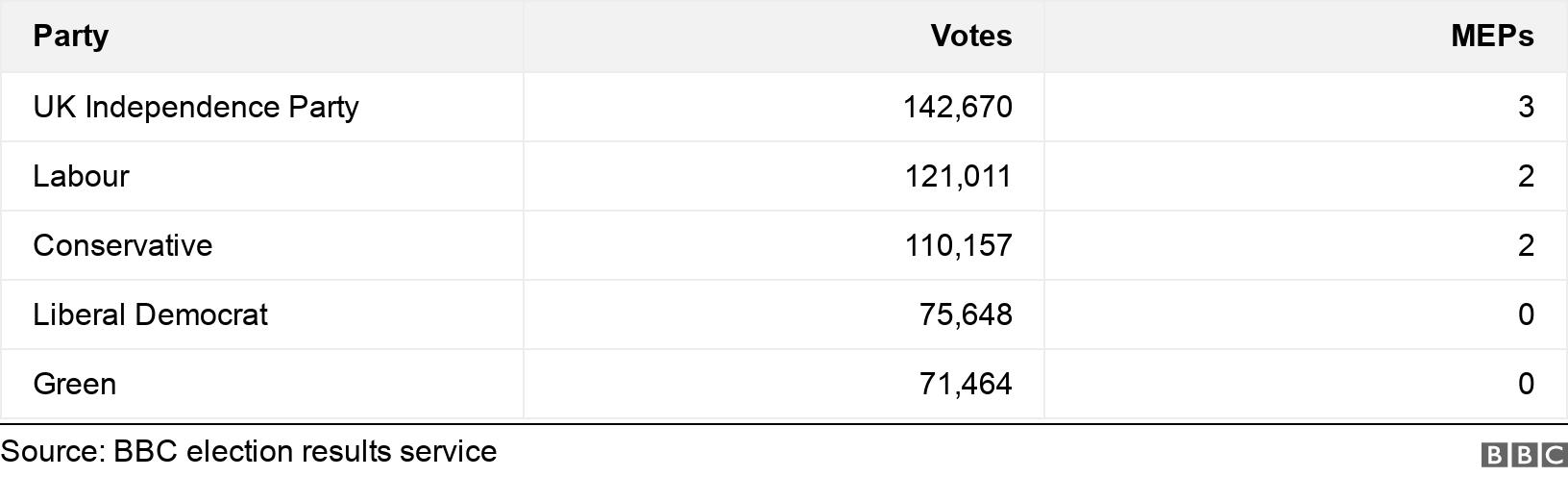

Round four

After the Conservative vote has been divided by two, UKIP is back on top. The candidate in second place on its list is elected.

Round five

Since two UKIP candidates have now been elected, their original vote tally is divided by three (one plus the number of MEPs elected) and Labour secures top spot and a second MEP for the region.

Round six

The original Labour vote is now divided by three (one plus the two MEPs from round five), leaving the Conservative Party to top this round and win a seat for the second person on its list.

Round seven

The Conservative Party vote is now divided by three, leaving UKIP in first place to win the final seat for the third candidate on its list.

Single transferable vote

In Northern Ireland, a different system is used to elect its three MEPs.

Voters have a "single transferable vote", meaning that they are able to rank the candidates in order of preference.

To make the system work, officials first need to calculate a quota. They take the total number of valid votes cast, divide it by the number of seats available plus one, and then add one.

In the first round, if any candidate secures more first-preference votes than the quota, they are elected.

Surplus votes, ie those received above the quota, are redistributed among the other candidates.

If not enough candidates have yet reached the quota, then the candidate with the lowest number of votes is eliminated, and the lower-preference votes of their supporters are again re-allocated.

This process is repeated until the three posts have been filled.

- Published5 December 2019

- Published14 May 2019

- Published8 May 2019

- Published22 May 2019