Oliver Letwin: Why we don't say Big Society any more

- Published

The Big Society is still alive - but Conservative ministers do not talk about it any more to avoid upsetting the Lib Dems, Oliver Letwin has said.

The Cabinet Office minister said he used the phrase "frequently".

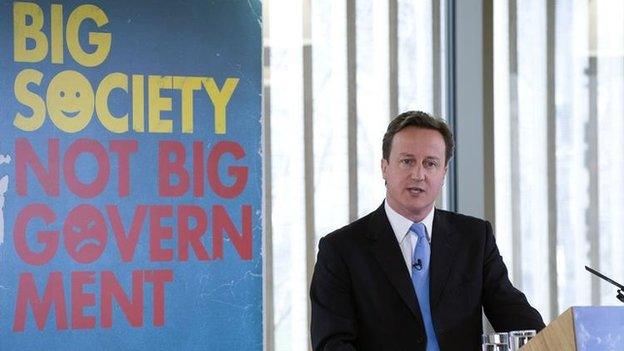

The Big Society - giving more power to communities and backing voluntary action - was David Cameron's flagship policy at the 2010 general election.

But it appears to have fallen out of favour after being the target of mockery by critics and some Tory MPs.

Plans for an annual Big Society day have been put on hold.

Speaking to BBC News in March, Big Society Minister Nick Hurd denied the term had become an embarrassment, adding: "Arguably, every day is a big society day."

Prime Minister David Cameron still appears to hold the policy dear too, telling an Easter reception in Downing Street: "Jesus invented the Big Society 2,000 years ago - I just want to see more of it."

Mr Letwin shed light on why we do not hear very much about it any more, at an Institute for Government event on Tuesday.

Housing bubble

He claimed successful government policies such as mutualisation, where groups of workers take over the running of public services, and payment by results for volunteer groups, were all "fundamental components of the Big Society".

But he added: "In deference to our Liberal colleagues in the coalition we haven't majored on the phrase, but the idea is exactly what I am talking about."

Pressed further on why the Big Society had fallen out of favour, he said: "I think it's an excellent description of it and I continue to use it frequently - but I don't really care what the description is, what I care about is the progress."

In February 2011, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg's aides were forced to deny reports he had banned the use of the term in the Cabinet Office, which he shares with Mr Letwin, but, they added, the Big Society was a "Conservative idea".

At the time, Mr Clegg said his party shared Mr Cameron's commitment to the values of the Big Society, but "Liberal Democrats tend to talk about community politics or just Liberalism".

Mr Letwin, who gave a lecture on the changing nature of the state, said neighbourhood plans were the best example of the Big Society - and could even help prevent another "unsustainable" housing bubble by clearing the way for new development.

'Popular resistance'

Neighbourhood plans were launched in 2012 to give local communities more say over the planning process, including where new homes and offices should be built and what they should look like. If local residents back the the plan in a referendum all future planning applications are judged against it.

About 1,000 neighbourhood plans are in various stages, with some already complete.

Far from limiting new development, as some had believed they would, Mr Letwin said people were more inclined to back new homes if they had control over the process through a neighbourhood forum and did not feel they were being dictated to by Whitehall or their local authority.

He said: "The most interesting thing about neighbourhood planning is that it has led, in many cases, to places authorising more houses to be built than would otherwise have been foisted on the neighbourhood but with no popular resistance."

But research by planning consultants Turley, external, published in March, suggested that, so far, most neighbourhood plans had been used to resist development and "maintain the status quo" with only a "small minority" of them encouraging growth.

"This suggests a potential for conflict between localism delivered through neighbourhood planning and the positive presumptions and growth that underpin government policy," said executive director Rob Turley.

- Published7 January 2013

- Published14 February 2011