Hints of defeat in UK battle against Juncker

- Published

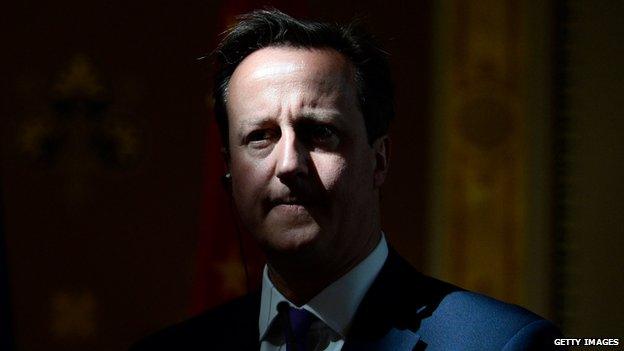

David Cameron was clear. Despite being at odds with many EU leaders, he would continue to oppose the nomination of Jean-Claude Juncker as the new head of the European Commission.

It was essential, the prime minister said, that Europe's elected heads of government chose the new boss of the EU's executive body and not the European Parliament.

"I will go on putting forward that principle, and opposing this process of having someone put on us by the European parliament through a fairly strange set of elections," he told a Downing Street news conference.

"I'll go on opposing that right up to the end, there is absolutely no question of changing my view about that."

But note that hint of resignation in his words. He spoke twice of arguing "right up to the end" and did not mention Mr Juncker by name once.

The mood at Westminster is that we are heading to the end game on this battle, an end game that Britain might not win.

"It is going to be tough," said one government official. "It's an uphill battle. We are realistic."

Mr Juncker, a former prime minister of Luxembourg, is supported by Europe's centre-right parties who did best in the recent European elections.

They think that new EU rules in the Lisbon Treaty allow them to nominate him as their candidate.

But the prime minister thinks Mr Juncker is not the right man for the job, that he is too much of a Brussels' insider to make the reforms that Europe needs.

As his Europe minister, David Liddington, told MPs today: "It is very important that the Commission is led by a man or woman who has the energy, drive and determination to take through an agenda of economic and political reform and face the very serious challenges Europe as a whole confronts, not least getting back to work the millions of jobless youngsters in Europe."

And they don't think Mr Juncker is that man.

Some EU leaders privately share Mr Cameron's concerns about what he sees as a power grab by the European Parliament.

But many do not appear prepared to oppose Mr Juncker because they would pay a political price at home.

So Mr Cameron's problem is that although he has some allies, he has more opponents - including Germany's Chancellor Merkel - and they are hoping to push it to a vote at a summit next week, a vote that at the time of writing the UK would lose.

Downing Street officials insist they have not given up hope.

They say there are ten days to go until the summit. In private, ministers past and present can be extremely rude about Mr Juncker. And British diplomats are clear that many EU leaders express similar doubts about Mr Juncker in private even if they refuse to repeat them in public.

Downing Street hopes that by standing firm, Britain will legitimise dissent and allow others to break cover. They also hope that other EU leaders might worry about the precedent being set by allowing the parliament to rewrite Europe's rules on the move and change the way these appointments are made.

British ministers are still putting their hopes in a vital meeting on Wednesday between the Italian Prime Minister and the current head of the European Council, Herman Van Rompuy, who is the man charged with making a deal.

Matteo Renzi has yet to make up his mind who to support and Downing Street is still looking to win his support. But some in London fear that Mr Renzi is playing hardball simply to win EU permission to ease up on Italy's austerity programme in return for supporting Mr Juncker.

Either way, hope is fading for a British victory. So minds in Whitehall are beginning to turn to the end game. In return for accepting Juncker as president, could Britain win a consolation prize in one of the powerful portfolios when the rest of the Commission is formed?

Top of the UK's wish list would be for its commissioner to be in charge of the internal market, competition, trade or energy. Talk of Britain getting a beefed-up vice-presidency of the Commission in charge of a cluster of commissioners is dismissed on all sides.

Some Tories are shaping arguments that describe Juncker as a potentially weak Commission president who would be more malleable to the wishes of the EU's leaders. "He would have to do as he was told," one said. "It would be quite a different case if he were a more powerful figure like Lagarde" - a reference to the French IMF chief Christine Lagarde.

There is also the suggestion that Juncker's presence might make some EU countries take the UK's reform agenda more seriously. Others say that Juncker could be ignored because many of the EU reforms that Mr Cameron wants to achieve will be decided between governments and not with the commission.

But these kinds of arguments are the political equivalent of whistling in the wind to keep up your spirits.

David Cameron has gone out on a limb in this battle and defeat would be a defeat.

He has invested a fair chunk of political capital in this battle. It has set him against the German chancellor, a woman he will need as an ally in any future negotiations.

And many MPs and voters will ask a simple question: if the prime minister cannot win over his EU counterparts on this, what chance will he have of persuading them to accept big reforms to the way the EU operates ahead of a possible referendum in 2017?