Assisted Dying Bill: Can it become law?

- Published

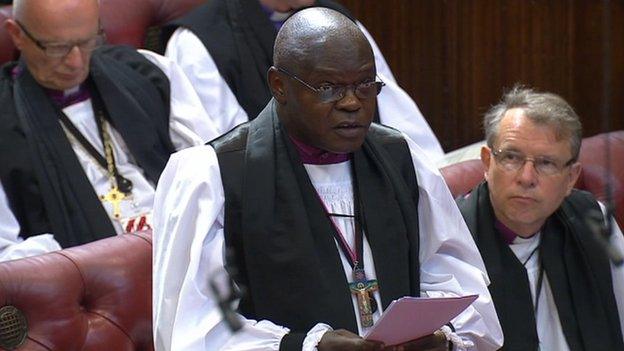

The Archbishop of York said coming to terms with one's own death was a "gift"

What happens next?

As I write, the Lords are still debating the Second Reading of Lord Falconer's Assisted Dying Bill, and it is one of the best, and most moving, parliamentary debates I've ever reported.

I very much doubt that the Bill will be stopped at the vote later this evening - firstly it would be a breach of the normal proprieties to do so, especially without the expected courtesy of putting down a fatal amendment a couple of days before hand.

And in the Lords, these things matter a lot. Second I doubt the support exists to block it - partly because of the level of outright support for the Bill and partly because even many of those who disagree accept that something needs to be done, and a debate should therefore be had.

So the Bill will eventually go into Lords Committee Stage scrutiny in October, and may well require several days of debate in front of the whole House.

It looks unlikely that the Bill would complete its final stages, Report and Third Reading, much before Christmas (the Lords is pretty busy at the moment).

Making the slightly less safe assumption that the Bill is given a Third Reading, that is where things judder to a halt.

Passions are running high on both sides of the debate

There is no requirement at all for the Commons to find debating time for Lords Private Members Bills.

As Lord Steel found to his chagrin, after getting his House of Lords Bill through the Upper House, it simply languished, undebated, in the Commons.

For the Falconer Bill to have a realistic chance of becoming law, the government will have to provide debating time in the Commons. And as David Cameron made clear at PMQs this week, it's not keen to oblige.

What we may get, if enough MPs are prepared to stick their necks out that far, is a debate scheduled via the backbench business committee.

It might be a general debate, perhaps informed by the Falconer Bill; but it might get more interesting if there was an actual motion, perhaps calling for time to be allocated to allow a Second Reading in the Commons.

In the run-up to a general election, maybe most MPs would rather not go there, so it may well be that any debate is consciously kept very non-specific.

Now Lord Falconer is a gnarled political professional who undoubtedly read the lie of the legislative land well in advance; I suspect his real objective all along was to extract a clear manifesto commitment from all the main parties to allow a bill to be debated in government time in the Commons, safely after the next election.

The Supreme Court wants Parliament to act; but the Supremes shouldn't hold their breath.