Do lab monkeys suffer from depression?

- Published

Do monkeys who have never known anything different mind being subjected to repeated experiments on their brains? It is a question that the Home Office is currently examining.

This will seem an absurd question to many people.

The thought of our closest cousins in the animal kingdom - creatures known to have complex emotions and feelings - having parts of their brain removed or coils implanted in their eyes so scientists can run tests on them sounds abhorrent.

Researchers insist there is no alternative if we are to find cures for Parkinson's Disease and other conditions and test vital new drugs. The Home Office takes into account the "severity" (others would say cruelty) of a proposed experiment before issuing a licence.

But until recently no one had given much thought to how the monkeys stand up to repeated experiments - some of them can be operated on as many as 10 times over a period of years - or the psychological impact of a lifetime in the laboratory.

Researchers say most monkeys, who have been bred and trained for laboratory work, do not put up a fight when experiments are conducted on them. Does that mean they have given their "consent"?

'Behavioural problems'

Do they find it a positive experience? Or is their passivity down to the fact that they are suffering from severe depression?

The answers could have far-reaching implications for the future of animal experiments in the UK.

An EU directive came into force last year forcing regulators to consider the lifetime impact of experiments on monkeys, rather than just focusing on one experiment at a time.

It said "the nature of pain, suffering, distress and lasting harm caused by (all elements of) the procedure, and its intensity, the duration, frequency and multiplicity of techniques being employed" should be a factor in issuing licences.

But a few months later, a groundbreaking study into the lives of laboratory monkeys, external was published which claimed there was "little evidence" to back this approach up.

Dr John Pickard, of the University of Cambridge Department of Neurosurgery, and his team, spent 10 years studying non-commercial testing of marmoset and macaque monkeys - by far the most common breed in UK research labs since great apes and orangutans were banned in 1997.

They found that concerns about the impact of repeated procedures, which can include brain implants, the implantation of eye coils, prolonged restraint and the withdrawal of food and water, among many other things, have been overstated.

'Euthanised'

"For many lay people, the claim that such prolonged procedures can be carried out without cumulative (negative) severity may be difficult to believe. Too often the public is uninformed about what really goes on in primate experiments," said the report.

"For example, animals are increasingly chosen for their suitability and aptitude for research procedures. Animals that are unsuitable are not then exposed to a prolonged training period."

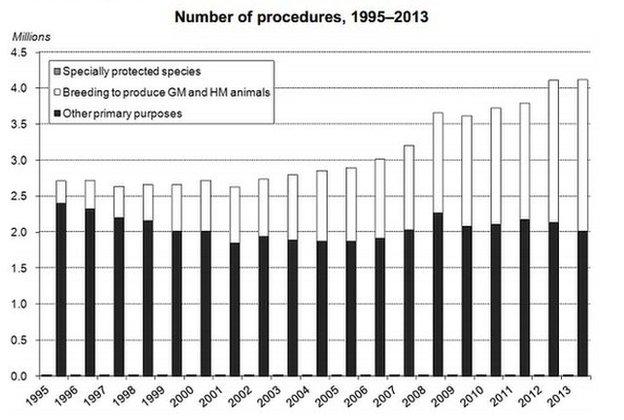

The rise in the total number of procedures was 0.03% between 2012 and 2013

The 234 animals in the study, at British and EU universities, were, for the most part, well looked-after and had not been removed from their mothers at an age below that recommended by the Home Office, the report said.

Animals who refused to be subjected to procedures were sent back for retraining. In a small number of cases, monkeys could not cope with the experiments and were put down.

For example, one macaque developed "severe behavioural problems" including "stereotypy" - repetitive nervous actions such as rocking - and had to be "euthanised".

In animals which had had sections of their brains removed, "epileptic seizures were seen in a number of cases," the report adds.

Physical distress

The Pickard report identifies ways to improve the welfare and well-being of monkeys used in research - and suggests greater use of CCTV to monitor behaviour.

But it was met with dismay by animal rights campaigners, who argued that the suffering of monkeys in laboratories was self-evident and morally wrong.

The independent committee that commissioned the Pickard report has now been disbanded - but its successor body, the Animals in Science committee, has rejected many of its findings.

In a report published this week, external, the ASC said Pickard "leant heavily" on physical signs of distress such as weight loss and not enough on emotional and psychological indicators.

It said the monkeys' apparent willingness to take part in behavioural tests should not be taken as a sign that it was a positive experience for them. They could be suffering from a condition known as "learned helplessness" - a form of clinical depression often seen in rodents subjected to repeated electric shocks. After a while, they do not seek to avoid the shocks, even when they had the opportunity to do so.

The Home Office is funding research into whether monkeys in laboratories suffer from depression.

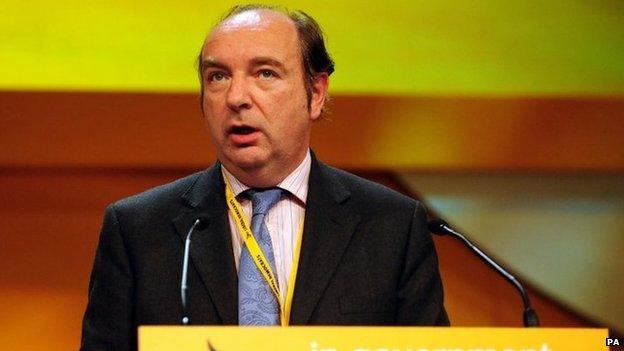

The British government is committed to reducing the number of live animal tests in the UK - the minister responsible for licensing, Norman Baker, has said he would like to see it banned altogether but concedes that is not about to happen any time soon.

'Severe harms'

It is big business - experiments on primates make up less than 0.5% of the more than 4 million procedures carried out each year in the UK with the mice, fish and rats the most common subjects.

This week, the Animals in Science Committee announced a fresh inquiry, external into the "lifetime experience" of monkeys used in neuroscience research.

Lib Dem minister Norman Baker wants to see all animal testing banned

In a letter to Norman Baker, committee chairman, Dr John Landers said the committee wanted to "revisit" Pickard's findings and was setting up a new "Harm/Benefit Task and Finish Group".

Barney Reed, senior scientific officer for the RSPCA, welcomed the change of heart.

He said the Pickard report had told us "how neuroscientists themselves perceive the impact of their research on primates, rather than providing meaningful information about the actual levels of suffering experienced by these remarkable and highly sentient animals".

And it had "systematically underestimated" the "significant and severe harms that can be caused to primates in the name of neuroscience research".

He added: "The RSPCA welcomes the fact that the Animals in Science Committee (ASC) recognised these fundamental shortcomings in the report's methodology and interpretation of the material provided by primate researchers.

"Despite these serious flaws, the Pickard Report does make some worthwhile recommendations relating to recognising and assessing suffering, reducing suffering, and improving the understanding of primate behaviour among researchers.

"In the RSPCA's view most of these should already have been common practice, but notwithstanding this, they should now be implemented without delay. The RSPCA completely agrees with the ASC that the recommendations should be revisited and aimed at specific organisations and individual roles, with milestones and measures of success, or they will simply be forgotten."

- Published31 July 2014

- Published14 March 2012