How Samantha Cameron's ancestor 'reinvented' walking

- Published

In the late 19th Century, thousands came to watch one of the most gruelling events in sporting history. And the man behind it all was the great-great-grandfather of David Cameron's wife Samantha.

As the clock struck one on that Monday morning, 17 Englishmen and a single Irish-American set off.

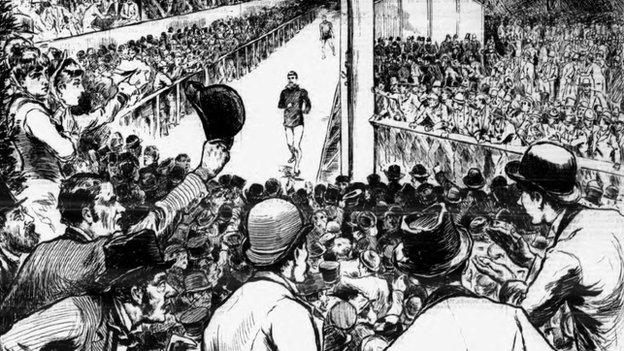

A military band played while bookmakers shouted the odds and the bars and restaurants of the Agricultural Hall in Islington, north London, teemed with customers. The more inebriated screamed at their favourites to get a move on.

The early morning of 18 March 1878 saw the start of what was described as the greatest sporting event in the world. The aim was simple but daunting - to get around the track as many times as possible over six days.

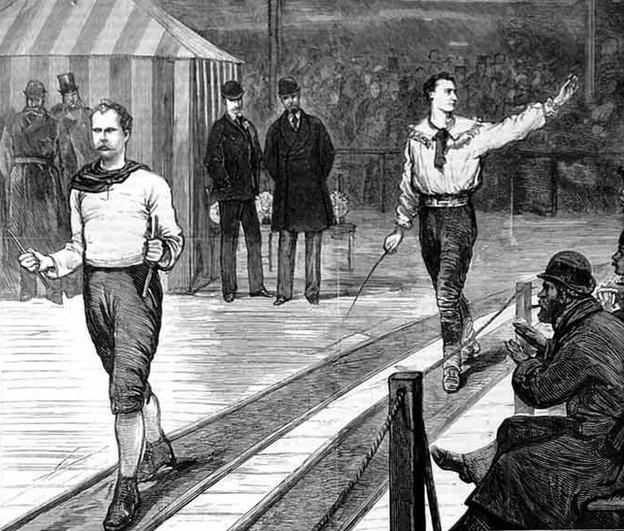

Under the rules of "pedestrianism", colloquially known as "go-as-you-please" racing, competitors could walk or run. Eating and drinking as they moved, playing up to the crowds - who also displayed considerable stamina - they plodded on and on.

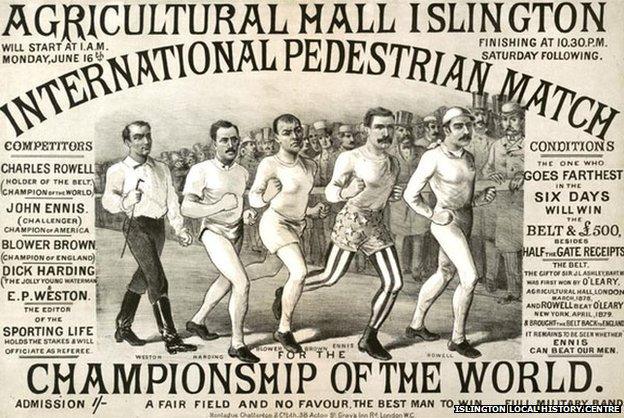

Their incentive in this race - the first of five in a "world championship" taking place in the UK and US - was a prize of £500 and the newly created Astley Belt. Thousands attended and the latest updates on proceedings dominated the front pages of the newspapers.

The man who put up the money and gave his name to the gold and silver-decorated belt was the Conservative MP for North Lincolnshire, Sir John Dugdale Astley, the great-great-grandfather of Samantha Cameron.

Known as the "Sporting Baron", this portly, bearded veteran of the Crimean War had been a runner in his youth and had gained a reputation as a prodigious gambler. His aim in creating the Astley Belt was to clean up a sport which was seen as disorganised and fixable.

"He was a respectable Conservative Member of Parliament," says Paul Marshall, author of King of the Peds, external, a history of the sport. "His involvement helped to legitimise pedestrianism. He wasn't really ruthless at all, but a very nice person. All he wanted to do was promote athletics.

"He was rather a pleasant promoter. He wanted to see pedestrianism develop good values. There were plenty of ruthless promoters who just wanted to make money for themselves."

Some other extreme endurance events

Tour de France - 2,100-mile cycle race lasting three weeks and including mountain stages and sprints

Marathon des Sables (above) - 150-mile run/trek through the Sahara Desert with contestants carrying food and supplies

Ironman triathlon - a 2.4-mile swim, followed by 112-mile bike ride and a marathon run

Touch the Truck - bizarre 2001 Channel 5 game show, in which the last contestant who kept their hand on a truck, without interruption, won the vehicle. The champion managed more than 80 hours

Pedestrianism had grown up since the mid-to-late 18th Century, encouraging ever more remarkable feats of physical endurance. The American Edward Payson Weston had attempted to walk 2,000 miles around the shires of England in exactly 1,000 hours, missing by just a few miles.

He was also a showman, Usain Bolt-like in his constant playing up to the crowd. "Weston used to keep on his formal clobber for a few laps before racing in his pedestrian costume," says Marshall. "He fooled around with a trombone sometimes and even spun plates on his walking stick as he competed."

The first of the Astley Belt contests was won by Daniel O'Leary, an Irish-born American, who managed 520 miles by the end of the sixth night. Six months later he took the second round at New York's Madison Square Gardens, a baying pit of excitement and betting, notching up 403 miles.

But, in the following March, he was forced to retire from the third race through exhaustion brought on from consuming too much champagne, wrongly perceived to be a stimulant. Weston won and the penultimate race, in September 1879, was taken by the muscular Charlie Rowell, who went on to keep the belt.

The achievements remain remarkable, as does the hype surrounding what was, after all, nothing more than a mixture of long-distance walking and running.

"The sport was pretty brutal, with contestants racing about 22 hours a day," says Marshall. "These men were seen as the gladiators of their time, a reminder of the contests in the Colosseum in Rome. People went mad for it. They couldn't get enough."

Followers spanned the class divisions of Victorian England. Aristocrats mingled with gangsters and down-and-outs who paid for entry so they could use the venues as a dry place to sleep for six nights.

Another, more tenuous connection between pedestrianism and the current prime minister's family was the presence of Scottish champion George Cameron. To gain a greater following he reversed his surname to Noremac. "Anyone could be called Cameron but this was something different and fresh," says Marshall.

The excitement of the Astley Belt contest was not to last. Astley himself continued to support pedestrianism, but newspapers began to comment more on the brutality of the contests and the vulgarity of the crowds. Financial rewards dwindled as spectators stayed away. In the US, baseball became the main spectator sport. In the UK, football and cricket dominated.

Still, the competitors kept plodding on. In 1882, George Hazael of England broke the 600-mile barrier for a six-dayer. Two years later Weston walked 5,000 miles in 100 days.

Is Usain Bolt the heir to some of pedestrianism's greatest characters?

Nowadays events like ultra-marathons - set over prescribed distances or against time limits - attract the masochistic and point-proving, but nothing like the same attention enjoyed by the pedestrianism champions of the 19th Century. Is there a place in today's more crowded sporting calendar for a revival?

"The thing with walking is that it's probably the least sexy of all sports despite the fact that it's obviously the most common activity in the world, next to breathing and sleeping," says Pete Davies of the RMS public relations agency, external.

"It would need huge investment to get the interest up and maybe some celebrity involvement. Perhaps someone with a clean, sporty image like David Beckham."

Another suggestion by Davies is the comedian Eddie Izzard, who completed 43 marathons in 51 days, external for the charity Comic Relief in 2009. "He's eloquent and famous and he's done something similar, so why not?"

Marshall is keener on someone with a historical connection to the golden days of pedestrianism.

"It would definitely be good to have Samantha Cameron as a patron, given the great work of her great-great-grandfather," he says. "I think pedestrianism would be a success if it came back. That would be amazing."