The Alex Salmond story

- Published

A look at Alex Salmond's career in SNP politics spanning more than 40 years from his student days to his role as first minister

He is the man who took a rag-tag bunch of political misfits to the brink of achieving their dream of an independent Scotland.

He defied the odds at every stage of his career, conjuring impossible victories at the ballot box and outmanoeuvring his political opponents with a trademark blend of mischief and guile.

As he departs as Scottish National Party leader and first minister, after losing Scotland's independence referendum, it is difficult to believe we have seen last of Alex Salmond.

He has bounced back many times before during his extraordinary 20 year career at the head of Scotland's independence movement.

And even as he announced his decision to quit, to make way, he said, for a new generation of leaders, there were hints that we had not seen the last of him.

So what was it about the ebullient, quick-witted former economist, who never seemed lost for words - except, perhaps, when he was contemplating the destruction of everything he had worked for since his student days - that made him such an effective political leader?

Salmond joined the SNP at St Andrews university

Despite his public image, Salmond is often described as a very private person. No one has ever doubted his commitment to the nationalist cause and the incredible drive and energy he has devoted to it during the course of his long career. But where did it come from?

Most look for clues in his modest upbringing.

There is still "something of the chippy, working-class boy who made it to St Andrews [university] and has been determined to show how much cleverer he was than everyone else," a former Salmond aide told David Torrance in his 2010 biography of the SNP leader Against the Odds.

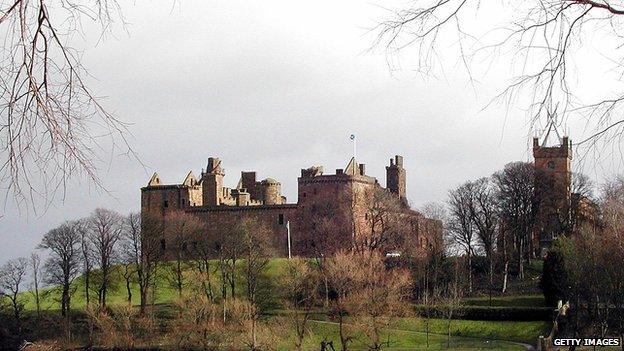

Linlithgow Palace was Salmond's gateway to Scottish history

After all, Alexander Elliott Anderson Salmond grew up on a council estate in Linlithgow, a small town in the central belt of Scotland, a traditional Labour Party stronghold. The second of four children, his father, a civil servant, voted Labour and his mother was, in Salmond's words, a "Churchill Conservative".

All four of the Salmond children went to university and it was a politically aware household. In an interview with The Independent in 2008,, external Salmond fondly remembers how Hogmanay celebrations, which fell on his birthday, invariably ended in a political debate in the small hours.

'Beautiful swing'

His enthusiasm for sport - and Heart of Midlothian football club - predated his interest in politics although his asthma restricted his prowess on the football field. He got his lifelong passion for golf from his father and, according to David Torrance's book, played most Saturday mornings from the age of five. The result, he told The Independent, is "a beautiful swing, a wonderful swing, but I can't chip or putt any more".

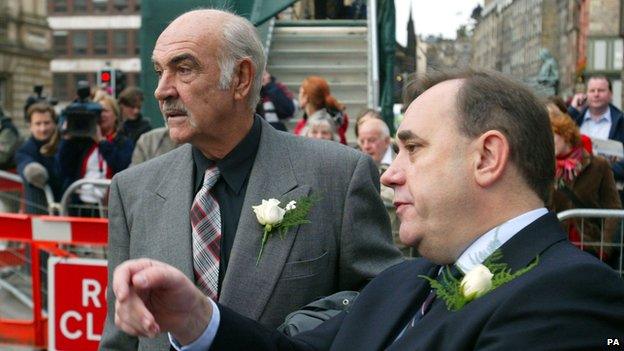

Golfing pal Sean Connery was drafted in to boost the party

Horse racing was another early passion. Salmond likes to recall his first bet, at the age of nine, when his uncle put half a crown on Arkle, the winner of the 1964 Cheltenham Gold Cup, and they crowded round the family's black and white television set to watch the race. Salmond wrote a tipping column for The Scotsman and continues to enjoy a flutter.

He always cites his grandfather, who filled him with tales of Scottish history, as a source of inspiration. The family lived a short walk from Linlithgow Palace, birthplace of Mary Queen of Scots, and it was here that the young Salmond began to learn about his country's bloody past.

"The most important person in my life was my grandfather," Salmond recently told broadcaster Derek Bateman., external

Sarah Smith takes a light-hearted look at the life and times of Scotland's First Minister, Alex Salmond

"He was the town plumber in Linlithgow. And my grandfather was a local historian. He was a national historian. He took me around Linlithgow. He showed me where all the great things had happened. I got Braveheart from my grandfather's knee."

Salmond often recalls the time a Labour Party canvasser came to the door. "That's OK," said the Labour man, when told about Mrs Salmond's Tory allegiances. "Just as long as she's not voting for the Scottish Nose Pickers." His father, who was friends with an SNP supporter, was so incensed by the slur that he switched to the nationalist side, and his young son followed suit. Or so the story goes.

His political roots set, Salmond took to campaigning for the SNP from an early age, even winning a mock election for the party at his primary school by promising to replace free school milk with ice cream.

'Blazing row'

But he did not cut his ties with Labour and join the SNP officially until he got to St Andrews University, where he studied medieval history and economics. He got involved in student politics but was growing increasingly disillusioned with Labour's commitment to the Union.

"I had a blazing row with a [Labour-supporting] girlfriend from Hackney and she said 'if you feel like that - go and join the bloody SNP', so I did," he told The Guardian in 1991.

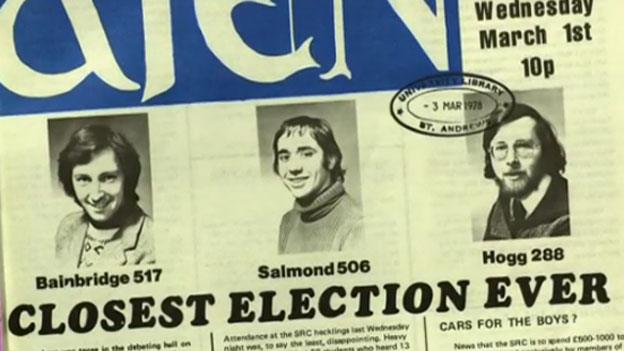

The student Salmond was serious about his politics

According to David Torrance's biography, Salmond and a friend went to the AGM of the university branch of the Federation of Student Nationalists the following day and, being the only two fully paid-up SNP members on campus, they were duly elected president and treasurer.

Salmond was "very serious about politics" at university, says BBC Scotland political editor Brian Taylor, a St Andrews contemporary, but he was also "motivated by mischief", something that is still evident in the SNP leader today, he adds.

After leaving St Andrews, Salmond was unemployed for six months. He is reported to have considered becoming a Church of Scotland minister, and attempted to get a job in journalism with the BBC, before passing the civil service exam and starting work as an economist in the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries for Scotland, in Edinburgh.

It was here that he met and fell in love with his future wife Moira.

Much has been written about the 17 year age gap between the couple - he was 27 and she was 44 when they married - and the fact that she has stayed out of the spotlight.

Rough edges

Some Salmond-watchers see significance in the fact that the couple do not have children. Did that make him even more determined to leave something lasting behind?

Salmond is quick to dismiss such talk, and equally quick to praise Moira's loyalty and grace.

Moira Salmond has stayed out the spotlight

In her only media interview, nearly 25 years ago, she said: "I married Alex not politics. That's his life and I am happy to be in the background."

She also revealed that they liked to play Scrabble together in the home they share in the Aberdeenshire village of Strichen, although they sometimes fell out because Salmond kept changing the rules.

She is, by all accounts, a well-liked figure in the party and is thought by those closest to Salmond to be a key factor in his political rise.

She is often credited with knocking some of the rough edges off Salmond and giving him a more mature outlook. She even taught him to drive shortly after they were married.

Salmond was a committed socialist at this stage and starting to make waves as a firebrand speaker at SNP gatherings.

Frustrated by life in the civil service, he managed to land a prestigious role as an economist with the Royal Bank of Scotland, specialising in oil and energy markets.

Sorry state

His new job strengthened his commitment to independence still further, he told The Guardian in 1991, "exposing for me a mythology I grew up with: that Scotland was a small, poor, dependent country reliant on munificence from outside".

This is a common theme whenever Salmond is asked about the roots of his nationalism - his belief that Scotland has what it takes to go it alone as "a country which can hold its head up".

Salmond and John Swinney were not always this close

But the SNP in the early 1980s was in a sorry state.

The party had been dealt a body blow by the result of March 1979's Scottish devolution referendum. The majority of Scots that took part in the vote backed home rule - but the Labour government had set a threshold of 40% of the total electorate for the result to stand.

In the general election that followed, the SNP lost nine of its 11 MPs and looked like it might he heading for extinction as a political force.

Salmond had hitched his star to the "79 Group", a small band of left-wing rebels dedicated to transforming Scotland into an independent socialist republic.

They managed to get up the noses of the party's traditionalist wing, which held sway under the moderate, centrist leadership of Gordon Wilson. In 1982, after one publicity stunt too many, and controversial efforts to forge links with Labour supporters, seven of the group, including Salmond, were expelled from the party.

'Tartan Tories'

The ultra-nationalist - some would say neo-fascist - Siol nan Gaidheal faction was expelled around the same time as Wilson battled to stop the party from splitting.

Salmond was only re-admitted when he signed a loyalty oath - but he continued to be frustrated by the party's lack of political direction. Its conferences brought out an odd mix of angry socialists in leather jackets, broadsword-wielding men in kilts dreaming of William Wallace and tweedy former Conservatives.

Salmond and former miner's leader Arthur Scargill show solidarity with striking Timex workers in 1993

"Because we weren't anchored to a political base, we were vulnerable to being called all sorts of ridiculous names; tartan Tories and tartan Trots at the same time. If you don't own up to a particular identity, you can't complain if someone pins one on you," said Salmond in 1991.

His mission was to carve out a distinct, left-wing political identity for the SNP. Something that would appeal to traditional Labour-voters in West and Central Scotland - voters that would be key to any future independence referendum.

In 1987, he defeated Tory MP Albert McQuarrie in Banff and Buchan to win a seat in the House of Commons. Now, at last, he had the national stage he needed for a bit of trademark Salmond mischief.

The following year he grabbed headlines around the world by interrupting Conservative Chancellor Nigel Lawson's Budget speech.

"What I said, although they turned my microphone off, was 'Poll tax for the poor, tax cuts for the rich, nothing for the National Health Service - an obscenity!' That was my wee speech," Salmond recalled earlier this year in an interview with Derek Bateman.

'Notoriety'

The sitting was suspended for more than 20 minutes as MPs voted - by 400 to 23 - to expel the SNP troublemaker. He emerged to a sight that would soon become very familiar to him - a media scrum begging for a soundbite for the evening news.

"I walked out from total nonentity to notoriety," he recalled decades later, still relishing the moment.

"It was a very astute thing to do, but that was Alex Salmond," says Murray Ritchie, former Scottish Political Editor of The Herald. "He was an opportunist of considerable talent."

His next goal was the party leadership and in 1990 he got it, after a divisive battle with the only other contender, SNP grandee Margaret Ewing.

In one early coup he persuaded his golfing pal Sean Connery to star in a party political broadcast - his financial support for the party had reportedly almost cost the James Bond actor his knighthood.

Salmond began to move the SNP in a more moderate direction, easing back on some of his earlier left-wing rhetoric and talking about how an independent Scotland would seek to join the European Union. He began to make the economic case for independence more loudly, and shift perceptions of the party as a bunch of narrow "little Scotland" nationalists.

He recently revealed that he is haunted by Michael Foot's withering put down of David Steel, that he "went from boy wonder to elder statesman with no intervening period whatsoever." He took the decision to grow into a more statesmanlike figure, someone who could lead a country not just a pressure group.

Many of the heavyweights that might have proved a threat to his supremacy in Scotland, such as Gordon Brown, Charles Kennedy or Alistair Darling, chose to make their careers in London, leaving the field clear for Salmond to dominate.

He kept the party's commitment to a fully independent Scotland but joined forces with Scottish Labour Leader Donald Dewar and Scottish Lib Dem leader Jim Wallace to campaign for devolution in the 1997 Scottish referendum.

'Dictatorial'

The fundamentalist wing of the party - the "fundies" - scented betrayal. Their anger was further stoked when news came through that Salmond had accepted an invitation to tea with Prince Charles. The SNP man explained his ideas for a "slimmed down monarchy" to the heir to the throne. While Salmond may have thought he was playing the long game, to his growing army of internal critics it looked like he was consorting with Scotland's enemies and his "gradualist" philosophy was just a polite way of saying he had sold out.

And there was another problem.

The SNP leader had always been something of a lone operator. Despite his clubbable image, he never had a large circle of friends or even much of a fan club within the party itself. He was described by critics as "aloof" and "intellectually arrogant". Now they were calling him "dictatorial".

The former republican struck up a friendship with Prince Charles

It did not help Salmond that the party was struggling to make headway against Labour at the ballot box. The best it could manage in the first elections to the new Scottish Parliament, in 1999, was becoming the main opposition to the Labour-Lib Dem coalition government.

Independence Day had been put back again. "Free by '93" had once been the SNP's battle cry. Now Salmond was talking about 2007. Some nationalists believed their newly-pragmatic leader would have been happy to settle for much less.

In 2000, Salmond got into a spat with one of his most vocal critics over the party's finances and then - to the surprise of most observers, for whom the SNP was Alex Salmond - he stood down as leader.

Telling the media he was "knackered", he quit his Scottish Parliament seat to concentrate on life as an MP at Westminster.

Swagger

His exile lasted just four years - during which time John Swinney led the party - before grassroots members begged him to return.

"I did not expect to be ever doing the job again, however time and circumstances change," he told a news conference with his choice of deputy, Nicola Sturgeon, at his side.

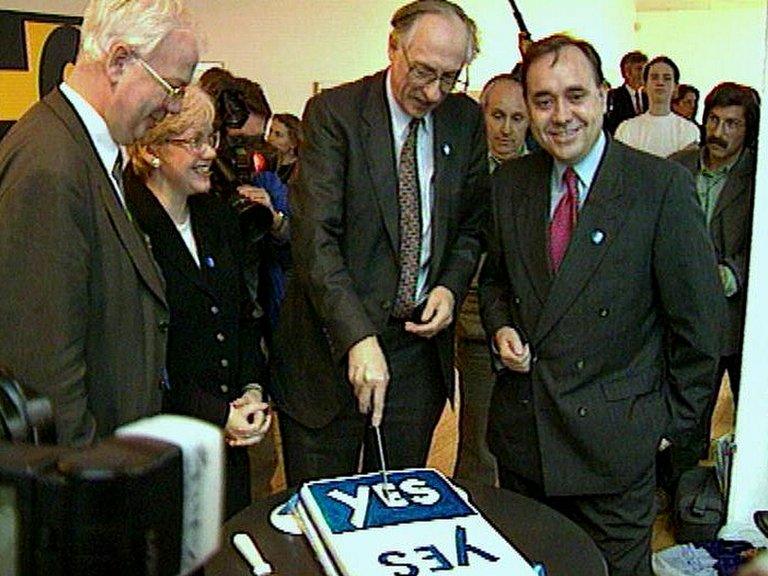

Salmond's decision to team up with Labour and Lib Dems in the 1997 referendum angered some in his party

"I am not just launching a campaign to be SNP leader," he told reporters. "I am launching my candidacy to be the first minister of Scotland."

The old swagger was still there - but there were serious doubts about whether he could ever win the majority he would need to secure a referendum in a Scottish political system specifically designed to prevent one party rule.

Not for the first time, Salmond's opponents, particularly those in the Scottish Labour Party, underestimated him.

The SNP broke the system. If Labour was shocked to lose to the nationalists by a single seat in 2007, ushering in a minority SNP government at Holyrood with Salmond as first minister, it was nothing compared to what was to come.

With a 15-point lead in some polls, the 2011 Scottish election was Labour's to lose - and that's precisely what they did.

Alex Salmond made history by becoming first minister in a majority Scottish government and, after all the decades of frustration, false starts and in-fighting, a referendum was now on the table.

The only problem, claimed the pundits, was that Salmond, ever the canny strategist, did not really want one. At least not now, with the global financial system in meltdown and any hopes of signing up to the euro, becoming the next "Celtic tiger", having disappeared down the drain.

'Political conjuror'

So confident was Prime Minister David Cameron - he had seen the polls putting the pro-Union camp 20 points or more ahead - that Salmond did not want a referendum that he took to taunting him from the Conservative Party conference stage to name a date.

When the two men finally sat down to hammer out an agreement on the referendum, many Westminster pundits thought Cameron had outfoxed Salmond by refusing to allow a third question on the ballot paper.

The economic case for independence has always been central to Salmond's pitch

Cameron was confident that the SNP could not win in a straight yes/no contest, so rejected Salmond's demands for a third "devo max" option - more powers for the Scottish Parliament in lieu of full independence - to be added to the ballot paper.

"He [Salmond] may well be forced to hold a referendum knowing that he will lose. The greatest political conjuror of recent times will have run out of tricks," wrote commentator Steve Richards in The Independent.

In the event, Salmond came far closer to winning the referendum than anyone thought possible when it was announced. The Yes campaign's late surge in the polls shocked the Westminster establishment into offering what may amount to a form of "devo max" after all, before a single vote had been cast.

Perhaps the old conjuror has a few tricks left up his sleeve after all.

Salmond called the referendum a once in a lifetime opportunity for the Scottish people. He will soon turn 60 and may not get another shot at it.

That, he suggested, was one reason why he had decided to step down as SNP leader. Twenty years as SNP leader, with a four year break, and seven years as first minister, something that has been "the privilege of my life" was, he said, a "fair spell".

But with characteristic defiance, he said Scotland "could still emerge as the real winner" and suggested his legacy was the tens of thousands of "energised activists" that had been drawn into politics through the Yes campaign, "who I predict will refuse to go meekly back into the political shadows".

He may have departed the stage but, he told the reporters, he would "continue to contribute" and said the dream of Scottish independence "will never die".