Aftershocks and apprehension

- Published

- comments

The aftershocks of the referendum will dominate the next parliament.

Here's why.

The best way of dealing with the "West Lothian Question", the former Lord Chancellor Derry Irvine once remarked, is not to ask it.

There was a time when the UK could simply ignore asymmetrical constitutional arrangements between Scotland (and to a lesser extent Wales and Northern Ireland) one the one hand; and England, on the other.

But that era is over.

Scotland emerges from the referendum campaign clutching an IOU for further devolutionary powers, signed by all the party leaders. But that promise to Scotland also requires an answer to that pesky West Lothian Question. It's named after the doughty Tam Dalyell (then the MP for West Lothian) who raised it during the debates on the Callaghan government's devolution plans, in the late 1970s - but it has been around in various forms since William Gladstone's Irish Home Rule Bill in the 1890s.

The issue is simple: how can it be tenable for Scottish (or in the 1890s, Irish) MPs to retain a vote on domestic issues like education and the NHS in England, when English MPs have no vote on the same issues in their patch?

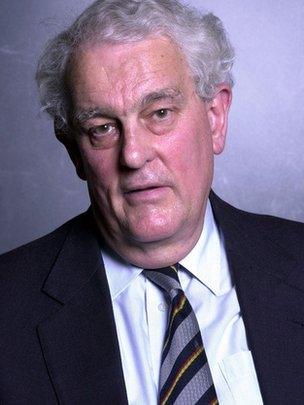

Tam Dalyell was the MP who first posed the famous West Lothian question

Post referendum, almost everyone in Westminster is calling for English devolution. The trouble is that there is no agreed vision of that that actually means - which is going to make politics through and after the next general election a messy business.

Constitutional dilemma

This morning David Cameron committed the government to drawing up proposals for some kind of answer to the English Question in parallel with the promised new proposals for Scotland. Or to put it another way: he's just pledged to solve a centuries old constitutional dilemma in a matter of weeks.

Which should be fun.

Already wise heads are shaking in Westminster. To some, the way to change the constitution is by slow, deliberative change. Essentially the ideal process is to clone the constitutional scholar Lord Norton of Louth, sit a dozen of him down in a committee room somewhere, take detailed evidence from the wise and the experienced and ruminate upon it for months - if not years - before producing a careful, nuanced set of proposals with a ready-made consensus behind them.

And that is an entirely sensible way to approach things. After all, the constitution is hardly a trivial matter and the rules of the political game should not be casually changed.

But for most politicians, the constitution is seldom much more than a debating weapon; while they may have an instinctive feel for the limits it sets upon them, they don't usually pay it much attention. And when they do it is because some raw political imperative has driven them there.

So, a hundred years ago Irish Home Rule and Lords Reform were driven by the needs of the Asquithian Liberal Party. Scottish devolution became a live issue in the 1970s, when it became essential to the survival (and instrumental in the demise) of the Callaghan government.

And it's why Nick Clegg's Lords reform plans bellyflopped; there simply wasn't the raw political energy behind them.

Speaking for England?

But an answer to the West Lothian Question is now urgent. And leaders from Nick Clegg to Nigel Farage are scrambling to speak for England. At issue will be not just the constitutional arrangements, but the promise from the main party leaders to keep the so-called Barnett Formula, under which public spending in Scotland is £1,500 a year higher per head than in England - which provides those not signed up to that promise with a nice, toxic campaigning issue.

(And, incidentally, watch out for Boris Johnson in this context. As Mayor of London, he has more voters and GDP than Scotland, and he presides over a ready-made institution, the Greater London Authority, to which new powers could easily be devolved….)

The problem is agreeing on an answer. Does it mean an English Parliament mirroring Holyrood? Does it mean non-English MPs leaving the Chamber in Westminster when England-only legislation is on the table? Does it mean devolution within England, and does that mean devolution to regions or to city regions, or to what? And while those may seem quite abstract questions they conceal some pretty basic power politics.

Getting Scottish devolution proposals through Parliament could be enormously difficult

Devolution to England as a whole (either via English-only votes in Westminster, or via a new, separate institution, with a steel and smoked-glass HQ in York, or somewhere) would probably mean Conservative majority rule in England, more often than not.

Devolution to regions or city-regions would mean more Labour enclaves.

So guess who favours which options?

And John Redwood, the formidable former Cabinet Minister who last week asked "who speaks for England?" put his finger on the key issue, with characteristic precision. If Scotland, and maybe in due course Wales and Northern Ireland, are to have power to set their own rates of income tax, and maybe other taxes, how can it be right for them to have a vote on the tax rates applied in England?

It's a simple, powerful point.

An English Parliament of some kind could credibly vote on big taxation decisions, but no-one seriously suggests that beefed up city councils or English regions should have mini-chancellors setting their own income tax rates. So if the English are to set their own taxes in the same way as seems to be promised to the Scots, they have to have a Parliament of their own to do it.

Internal devolution within England is not a substitute - although an English Parliament does not preclude yet more devolution within England. Indeed, the promise of more localised power may turn out to be a necessary sweetener to gain all party consent….possibly alongside a more proportional voting system.

And there's more...

Now contemplate the realities of getting the Scottish devolution proposals through Parliament after the 2015 election. As major constitutional legislation, this will have to be taken by a Committee of the Whole House of Commons (there are people who think this is an archaic way of doing business, but this might not be the moment to break with precedent) so, while the bill will undoubtedly get a second reading, the really dicey phase will be the detailed scrutiny process.

Will there even be a majority for a timetable motion? (The rock which sunk Nick Clegg's House of Lords Reform Bill, remember). Even if that is won, a small but determined group of opponents could still make life very difficult for whoever's in government.

And there will be opponents. Already a fair few Conservative MPs are criticising David Cameron for signing up to a pledge to retain the Barnett Formula. They will want some form of English self-rule and will need cast iron promises that it will be forthcoming - so devolution for Scotland will become a kind of hostage to devolution for England. The trouble is that concessions that buy off Conservative MPs could alienate the other parties, who will certainly not fancy the idea of Tory hegemony in an English Parliament.

Given an outright majority in the House, a Conservative government might be able to get an English votes/English parliament system through the Commons - but to do the same in the Lords (where no party has a majority) it would have to offer concessions to the other parties, on, as I suggested, devolution within England and possibly on the electoral system.

After all, Labour had to concede PR for the Scottish Parliament in the 1990s, to create a multi-party consensus around it.

The situation becomes even more fraught if there is no majority in the Commons - which is certainly possible, even probable. It is not hard to imagine a beefed-up contingent of SNP MPs (20 plus?) and some UKIP members making for very complicated parliamentary arithmetic. Meanwhile, expect some side deals with the smaller parties over powers for Wales and Northern Ireland to be struck.

It is going to be an incredibly messy way of dealing with some extraordinarily high-powered constitutional issues. It will almost certainly take a couple of years to put all the pieces in place, even operating at breakneck speed.

If our leaders get it wrong, the result may be a system which tears the UK apart, rather than bringing it together.

And finally - already there are calls, from such luminaries as Caroline Lucas and John Denham, to take the process out of Westminster's hands - at least to start with - and set up some kind of Constitutional Convention to thrash out the issues.

Keep an eye on that.