England-only votes: What are the options?

- Published

After the Scottish referendum debate, attention has turned to the constitutional impact on the rest of the UK

With the Scottish Parliament set to get more powers following the country's rejection of independence, what are the chances of wider change across the UK, including the idea of "English votes for English laws"?

What's going on?

Scotland voted against independence, but is still being promised more of a say over its own future.

This has led people in other parts of the UK to question whether they too should have more control over their own affairs.

Four options for "English votes for English laws" have now been put forward, external. Three of them are Conservative proposals, one has been put forward by the Liberal Democrats.

They are:

Barring Scottish MPs from any role in English and Welsh bills

Allowing English MPs to have a greater say over the early readings of bills, including in tabling amendments, before allowing all MPs to vote on the final stages

Giving English MPs a veto over certain legislation at committee stage

A separate Lib Dem plan to establish a grand committee of English MPs, with the right to veto legislation applying only England, with its members based on the share of the vote.

But don't we already have MPs to speak and vote for us?

The vast majority of MPs in the House of Commons represent English constituencies

Yes, but there's growing disquiet about the way the current set-up works, among both the public and MPs themselves.

Despite the devolution of powers to Scotland in the late 1990s, Scottish MPs at Westminster can still vote on issues affecting England only, such as its health and education policies. English MPs have no such power over Scotland.

This constitutional anomaly - known as the "West Lothian Question" - vexes many voters and MPs, particularly those on the Conservative benches.

Currently 41 of Scotland's 59 MPs are Labour, 11 are Liberal Democrats and just one is a Conservative. Many English politicians say reform is needed.

How many England-only laws are there?

It's hard to say. This is because the effects of a law can extend to other areas even if it does not directly apply there.

The McKay Commission, external, which carried out a review of the West Lothian Question for the government, said there were many ways laws applying only in England, or England and Wales, could still have "consequential effects" in the devolved nations.

For example, there is a tradition of "parity" between a devolved administration and Westminster in some policy areas, for example social security policy in Northern Ireland.

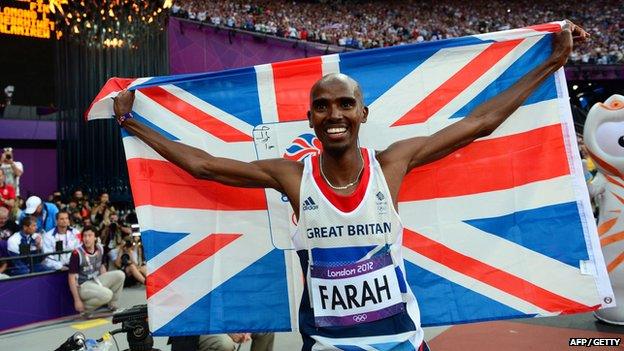

Was spending on the 2012 Olympics for England, or the United Kingdom?

There are also funding implications for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland when a spending commitment is made for England only, for example on the NHS. Under the current Barnett formula grant system, the devolved administrations' funding is adjusted to take into account changes to public spending in England.

This is often controversial, for example when spending on the London Olympics was deemed to be UK-wide, rather than England-only - triggering a row between Westminster and the devolved administrations.

For these reasons, according to House of Commons Library research, external, it is "not a simple matter" to count England-only bills. However, it adds that "whatever method is used, there are relatively few bills that unambiguously affect England only".

That's not the end of the matter though. There could be sections of a bill that apply only in England, even when the legislation itself extends across the United Kingdom.

This is why Commons Leader William Hague said "a very large proportion" of bills currently before the Commons could be affected.

The government's report says such decisions could be "technically complex and subject to political debate", suggesting the matter is decided either by the Speaker or through a Commons vote.

Why is this all coming to a head now?

Scotland is set to get control of Air Passenger Duty among other taxes

The three main Westminster parties agreed to give "extensive new powers" to the Scottish Parliament on issues such as tax and welfare if the country's voters rejected independence in the referendum.

Scotland's voters opted to stay part of the Union in the referendum, meaning the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats are duty-bound to follow up on their pledges. A draft parliamentary bill is being promised by the end of January.

A commission set up to examine the issue has recommended handing more control over income tax to the Scottish Parliament - including the power to set rates of income tax and thresholds at which these are paid for the non-savings and non-dividend income of Scottish taxpayers.

The commission also suggested devolving other taxes, including air passenger duty.

In addition, the Scottish Parliament would be able to agree the franchise for its own elections, meaning 16- and 17-year olds will be given the vote.

The Scottish Parliament, external already has powers over health, education, the environment and law and order.

But many politicians in England, particularly Conservatives, are concerned that this makes it even more pressing that Scottish MPs should stay out of English affairs. Some, it is feared, might vote against Scottish devolution plans if they don't get some movement towards change in England.

What is the Conservative leadership saying?

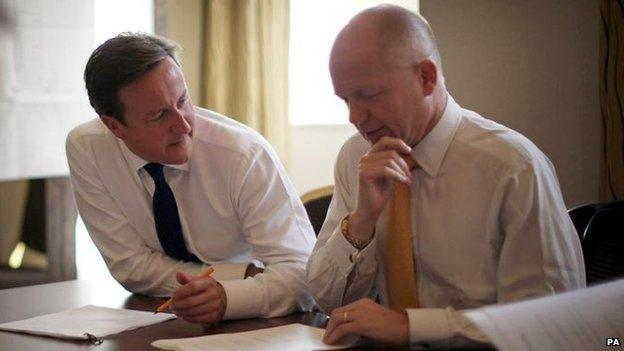

David Cameron has asked William Hague to draw up proposals for change

Just minutes after the outcome of the Scottish referendum was announced in September, David Cameron vowed to fulfil the pledge of new powers for Scotland but also said talks on a new settlement for England should take place "in tandem".

The prime minister has argued that, when the further Scottish changes come in, Scottish MPs should lose the right to vote at Westminster on issues that affect only England.

He asked Mr Hague to draw up plans for reform.

Mr Hague has selected the least radical option, which he says will give "accountability and fairness to England" at the same time as maintaining the integrity of the UK Parliament. Here is how it would work:

Before a Bill or parts of a Bill affecting only England is put to its final Commons vote, English MPs would meet separately to consider it

The Bill could not proceed without the backing of this English Grand Committee

In addition, only MPs for English constituencies would be allowed to take part in the committee stage, where the fine details are thrashed out and amendments proposed

But MPs from all parts of the UK would be entitled to take part in the final Commons vote passing the Bill into law

Mr Hague's proposals do not go far enough for some Conservative MPs, who argue that it will still hand too much influence to MPs for Scottish seats in the final Commons vote.

And Labour?

Party leader Ed Miliband would have more to lose in parliamentary terms if Scottish MPs are stripped of the right to vote over England-only matters, which would make it harder for any Labour government to get legislation through Parliament.

Newsnight's Andrew Neil grilled Chuka Umunna MP on Labour's plans for England following Scotland's referendum

He disagrees with the prime minister, saying his plans risk creating "two classes of MP".

Instead he is calling for a cross-party constitutional convention to take place, but not until after the election. This would, he says, take a wider, longer-term look at the situation facing the whole UK.

Labour has said it would back giving English MPs greater say over legislation related only to England, by introducing a new committee stage in the legislative process open only to MPs from English constituencies.

The opposition also wants to see devolution within England to regions and the House of Lords to be replaced with a "Senate of the Nations and the Regions".

What about the Lib Dems?

Nick Clegg's Lib Dems support "devolution on demand" in the English regions

Leader Nick Clegg says there need to be changes to the rules at Westminster to ensure a great say for English MPs over English-only laws - his suggestion is that legislation would go through a committee of English MPs.

The Lib Dems also favour more local devolution - or "devolution on demand" - with powers transferred from Westminster to cities, councils or groups of councils. The party also proposes a commission to explore future devolution options within England.

So, would this mean an English parliament?

Many Tory backbenchers want a separate English Parliament

At the moment, no. None of the three largest Westminster parties propose setting up an entirely separate body designed solely to create laws for England, as has long been demanded by the small English Democrats party and some Tory backbenchers.

But the UK Independence Party does want to see an English Parliament - leader Nigel Farage has also written to Scottish MPs asking them not to vote on England-only issues.

Will there be more powers for England's regions?

England's largest cities are clamouring for more powers

Possibly. The three main parties all say they want the regions - some with populations larger than Scotland's - to have more say over how they are run.

Mr Clegg has backed a report calling for large "city-regions" to get tax-raising and spending powers, with elected mayors at the helm. Labour and the Conservatives say they too want power to be decentralised.

But creating extra tiers of government has not proved popular with the English public. When 10 cities held a referendum on whether they wanted elected mayors in 2012, only one - Bristol - voted in favour. Similarly, voters in north-east England rejected setting up a regional assembly by 78% to 22% in 2004.

Can the parties reach a deal on England?

No agreement is likely before May's general election

They all said they could, but it is pretty clear that the answer is no. Labour has declined to take part in Conservative-led talks which they say are a "stitch-up".

Instead it looks like each will put forward their proposals to voters at next May's general election.

And what about Northern Ireland and Wales?

In Northern Ireland, the DUP says a vote on the future constitutional arrangement is not needed, with First Minister Peter Robinson saying "more and more" people want to maintain the status quo.

But Sinn Fein says Stormont should get more powers over taxation and government spending.

In Wales, Labour First Minister Carwyn Jones demanded a full say in any devolution talks, while Plaid Cymru leader Leanne Wood says Wales must get new powers if Scotland does, rather than being treated as "second-rate".

- Published19 September 2014

- Published19 September 2014

- Published19 September 2014

- Published19 September 2014