The next Parliament: Coalition 2.0 or confidence and supply?

- Published

Forming a second coalition may be much more difficult in 2015

It is beginning to dawn on MPs and peers quite how difficult it's probably going to be to govern after the next election.

The polls suggest a second, rather messier, hung parliament, in which forming a majority government looks tricky to impossible.

In 2010, the simple sum of Conservatives + Lib Dems = working majority made the current, fraying coalition government inevitable.

Next time, with (probably) fewer Lib Dems, (probably) more SNP MPs and (maybe) a significant UKIP presence and (perhaps) a couple of Greens there could be a range of possible governing combinations, but more than two parties would probably be required.

And stitching enough votes together via a sustainable five-year policy deal may prove pretty difficult.

The Lib Dems remain the most coalicious likely partner to one of the big parties, but both they and their current Conservative partners might take some persuading to renew their vows, post-election.

Both sides give every sign of having had quite enough of each other and it's not by any means a done deal that they will automatically accept coalition 2.0 if the arithmetic makes it possible.

Lib-Lab pact

Even if the leaders want it, there is a considerable risk of a second coalition being rejected by the troops on one side, or maybe both.

Which is why the phrase "confidence and supply agreement" is being muttered around Westminster. The last time one of these was used was the 1970s Lib-Lab pact, in which David Steel's Liberals promised to sustain Jim Callaghan's minority Labour government through budgets and confidence votes, in return for some modest policy concessions.

To some, confidence and supply is a parliamentary land flowing with milk and honey, where all of the angst of full-blown coalition is banished, but, somehow, all the advantages remain.

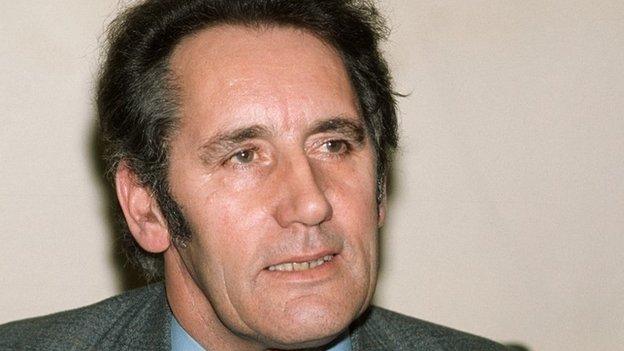

Walter Harrison kept the Callaghan government afloat in the 1970s

In this illusory land of wish-fulfilment, one of the big parties gets to govern as if they were a majority, without having to give house-room to those pesky minor parties. It ain't gonna happen.

The current coalition rests on a deal which requires its member parties to deliver their votes through the lobbies on all agreed coalition measures - and most especially the ones where they have to grit their teeth.

Hence the Lib Dems voting for welfare changes they probably didn't relish, while Conservatives had to support a certain amount of what David Cameron referred to as "green crap."

But confidence and supply means that the votes only have to be delivered on, er, confidence votes and budgets. Not on "bedroom taxes" or NHS changes or legal aid cuts.

So a minority administration sustained by such an agreement would probably need daily horse-trading to get its business through the Commons - and on unpopular measures those horses might bolt into the No Lobby instead.

Lords discipline

And that's before we get to the Lords. Most of the time the Lib Dem peers have been pretty disciplined about delivering the votes needed to get coalition business through the Upper House - more disciplined, some suggest, than their Tory colleagues.

But in the absence of an all-singing, all-dancing policy deal, they wouldn't have the same obligation to support uncongenial Tory or Labour measures, especially since they could not claim a mandate from the voters, as manifested through a general election victory.

A minority government would have a difficult time getting legislation through the Lords

The coalition has lost 100 Lords votes in this Parliament - even with strong whipping, while important bills have been filleted by peers.

A minority government would have a much harder time - and when those defeats bounced back to the Commons, it would have a harder time, still, trying to reverse them.

Some years ago, I interviewed the late, great Walter Harrison, the whipping genius whose dark arts kept the Callaghan government afloat, perhaps for longer than was good for it, or, in the end for Labour. For those who've seen James Graham's wonderful play "This House", Walter was the central character.

He did it by playing off the smaller parties against one another - but in the next House of Commons, those smaller parties may be rather bigger, there may be more of them, and they will have much more definite political objectives. They may peck a minority government to death.

And while there might seem to be enough policy common ground for the Lib Dems to switch their support to Labour, the personal chemistry - especially so far as Nick Clegg is concerned - looks awful.

Another problem is that if the Lib Dems are reduced to 30 or so MPs, or maybe fewer, they don't really have the numbers to sustain a full-on coalition.

They wouldn't have enough MPs suitable to serve as ministers, and probably wouldn't have more than two Cabinet seats so they would look more like passengers than junior partners in a Government.

Narrow mandate

But the arithmetic of the next Parliament is only part of the reason why it will be so difficult to construct an administration capable of lasting even a couple of years.

The rise of UKIP, the Greens and the SNP means more MPs than ever before may be elected on an extremely narrow mandate.

Take a look at the 2010 result in Norwich South, where Lib Dem Simon Wright won on 29.4% of the vote, a hair ahead of the former Labour Home Secretary, Charles Clarke on 28.7%, with the Conservatives on 22.9%, the Greens on 14.9% and UKIP on 2.4%.

Many more seats will see three, four or even five party politics at the next election, so it's not hard to imagine plenty of the next generation of MPs taking their seats on the basis of less than a third of the votes in their constituency.

They would have an acute sense of vulnerability. They would be under huge pressure to bring back the goods for their constituency, to deliver bypasses or new schools, fight local hospital closures, or fracking or whatever. And they could be vulnerable to constituency pressures on big votes.

Conservatives might feel the need to play to UKIP voters on Europe, Labour might feel vulnerable to insurgent Greens, so they could frequently face a choice between obeying the party whip now and defeat at the next election.

Now look at what the next House of Commons will have to deal with. Austerity, reshaping the UK and recasting the UK's relationship with the EU. Any one of these could break a strong majority government; a coalition, a minority government or a government with a tiny majority would face a constant struggle.

All of which means that the next prime minister will need Top Gun whips and fixers in both Houses of Parliament to get anything at all through at all. Without them, they're doomed.