The odd argument over public spending

- Published

George Osborne and other senior Conservatives delivered civil service estimates for how much some Labour policies will cost

British politics is a rather unfamiliar landscape at the moment: the share of voters who back none of the main parties is expected to reach an all-time high at this year's elections. Who knows how things will turn out?

Yet today, the Conservatives launched a campaign which feels very 1992. The Tories unveiled a re-run of one of their oldest campaign messages: "Labour cannot be trusted not to spend more than the country can afford".

In making that case, the Tories have - as is traditional for a governing party - produced civil service estimates for how much some Labour policies will cost. Next year alone, the Conservatives say, Labour would spend £23bn more than them.

But the whole exercise is a bit odd.

First, because we know that Labour do want to spend more than the Conservatives. There's no conspiracy here. As the Institute for Fiscal Studies says, Labour's fiscal rules imply it could "spend more or tax less to the tune of around £43bn in 2019-20".

Second, because as one senior civil servant put it to me: "It's fair to say that opposition costings are not given the same care as real ones. Which is to say, I do not think paying attention to them is a terribly good use of your time."

Just silly

In some cases, the government costings are just silly. For example, Labour has a policy of introducing a network of "director of school standards" to take on functions exercised by the Department for Education's local panjandrums and by local councils.

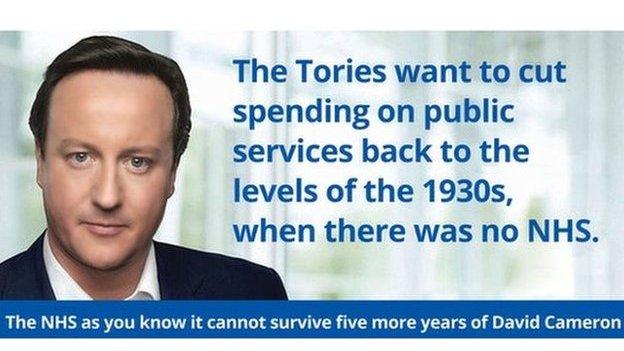

Labour has launched a poster campaign, mimicking the Tories' 2010 adverts

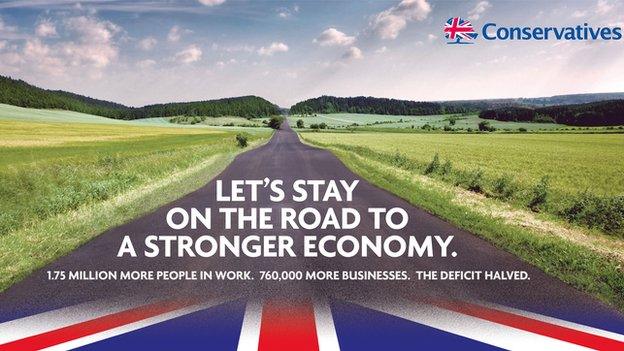

Meanwhile, the Conservatives' first campaign poster focused on the economy

Labour says there will be 40 to 50 of these people. But the official costing assumes there will be 150.

It keeps going: Labour thinks all classroom teachers should have a teaching qualification. But not, say, hockey coaches or piano teachers. But the DfE costing assumes that all of those people - along with conventional teachers - will all need to be qualified.

In some cases, the extra spending is not real. For example, part of the cost of insisting all teachers be qualified is higher pay for now-qualified teachers. The need for higher pay is a major part of the cost of implementing that policy.

But we fix the overall cost of schools and let head teachers sweat the details. So in the short term, the cost of higher pay for some will come from other teachers experiencing lower pay. It will not come from overall spending rises.

Not all the oddnesses go the Conservatives' way: costings for Labour's pledge on apprenticeships could have been higher, but for an error.

Still, it's rather odd that, when Labour's own plans imply that it could spend £43bn more a year at the end of the parliament, that the Conservatives have focused their efforts on a slightly dubious £23bn at the start.

There's a proper argument to be had here. And, in what I fear will be a constant refrain in the coming months, we still don't know about how spending squeezes in the coming years will be parcelled out among departments and spending areas by any of the parties.

That's really where the voters need detail.

- Published5 January 2015

- Published5 January 2015

- Published5 January 2015