Election 2015: Next government could be a long time coming

- Published

Who will still be standing after the May vote?

It surely will be over by Christmas, but still it is going to be a long war.

We know the general election will be held on 7 May but we don't know when exactly the spring peace treaty will be signed.

When it comes to war, I always say that I'm interested about why things go "bang" and how we stop things going "bang" and what happens once things stop going "bang", but the physics themselves hold a lesser fascination for me.

This time round it might be rather the same with the general election.

It will be an extraordinary election, even though journalists are already doing a good job of sounding jaded, giving the impression (I think for the sake of the audience) that they are already war-weary.

The long campaign itself springs from a unique situation - we know exactly when Parliament will be dissolved, external and thus the date of the election, as the UK's first fixed-term parliament comes to an end.

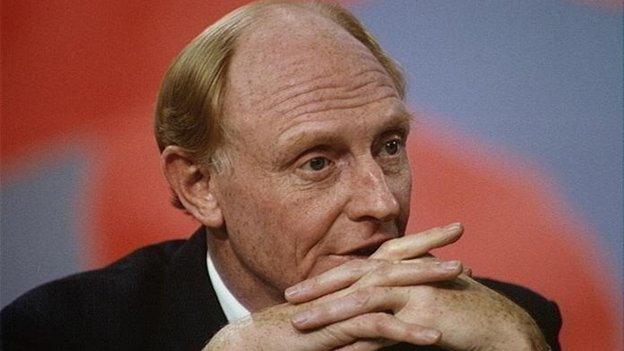

Both party leaders say this is a once-in-a-generation election, and it is certainly true that the opinion polls haven't been as tight since John Major won in 1992, when many thought Neil Kinnock had it in the bag.

The polls may well change, perhaps dramatically, during the campaign but it could be a nail-biter until the very end - and I doubt there will be any Sheffield rally.

Indeed, everything about this election is unusual - even the result. That might sound presumptuous with still three months to go, but Ipsos-Mori's Ben Page explains why it is true.

"It is going to be extremely rare, whatever happens.

"Only twice before in history has a government been in power for more than two years and actually increased its share of the vote.

"That is what David Cameron has to have happen. It happened twice in the 1950s - never before or since.

"For Mr Miliband to come back (after Labour's 2010's defeat) and form a majority government - that's only happened three times in the last 100 years and the last time was in the 1930s. So again very unlikely.

"And if we have another coalition, the last time that happened on two consecutive occasions was back in 1910, over 100 years ago. So pretty much any set of events is going to be unprecedented."

Multi-party politics

One of the main factors upsetting the apple cart is the coalition.

Doubtless over five years most people have got used to the daily reality of a two-party government. It blew apart many of our assumptions.

All my working lifetime we have had, if not two-party politics, two-and-a-half-party politics. (I am counting the SDP-Liberal Alliance in the 1980s as half a party).

Nick Kinnock lost in 1992 despite a healthy lead in the polls

But the undeniable dawning of three-party politics almost immediately ushered in an era of four-, five-, six-party politics.

The transmogrification of the Lib Dems, from the base metal of permanent opposition to the gold standard of the establishment, was not the only alchemy at work.

But the tarnishing of their reputation as opponents of the status quo did force people to look elsewhere for the philosopher's stone - some now see the SNP, UKIP and the Greens as the agents of real change.

You can almost taste the optimism in their new year messages:

The Greens, external say they can create peaceful revolution in 2015 - "a chance to reshape British politics".

UKIP's Nigel Farage, external has a surprise promise - no beer in January - but predicts voters will look outside the Westminster bubble for real solutions, devised by real people.

The SNP's, external message comes complete with a picture of the green benches of the Parliament turned tartan - it says Scotland could well hold the balance of power in a Westminster parliament. There is none of the piety of pretending they could win outright victory - and they are fairly explicit about their price for helping out in a hung Parliament.

Election promises perhaps matter more than ever this time round - politicians may not just be held to account by the electorate at some future date but by their peers in negotiations in the second week of May.

Last time around

Remember all the five agonised days of frantic high-pressure negotiations, external as politicians scurried furtively around Westminster sounding out their potential partners? You won't get that again. It won't be anything like that simple.

Negotiations in 2010 produced a rapid result

Damien McBride knows a thing or two about the dark arts of high politics - he was one of Gordon Brown's most senior advisers.

"I think it would be utter chaos. If we thought last time was chaotic, at least it was relatively simple," he says.

"At least it was just the Lib Dems having to make a choice between two parties, and it was pretty inevitable what they would do.

"What on earth is it going to be like this time when you have not only the Lib Dems but the SNP, potentially UKIP, potentially the Greens, potentially the Northern Ireland parties - and you end up with this chaotic shambles of negotiations going on on all sides?

"And crucially you could very well be in a position on the night of the election when Nick Clegg has to resign, or he might not even retain his seat - Labour are very confident about taking his seat - so who on earth is going to represent the Lib Dems?

"If you've got the public repudiating Ed Miliband, or David Cameron, are they going to be in a position to do a deal on behalf of their party," Mr McBride asks.

"The thing you would seriously worry about if you are in the civil service is that you would end up with the monarch, the Queen, roped into this because she ultimately has to ask someone to form a government, and that puts her in a constitutionally very difficult position."

If the Rose Garden news conference with David Cameron and Nick Clegg seemed rather like a wedding, complete with affectionate joshing between the pair, in May they or others may be looking for looser arrangements with their odd bedfellows, seeking perhaps friends with benefits.

No chaos allowed

But Lord Hennessy, the doyen of political historians, a long-term Whitehall watcher, told me the Civil Service won't allow chaos.

He said: "We are facing a Rubik's Cube of an election with multiple outcomes. But I think it is wrong to suggest the Queen will be embarrassed.

"There are two principles in a hung parliament. One is that the Queen's government must be carried on - the prime minister is expected to stay until it is clear from the negotiations between the parties who has got the greatest chance of commanding the confidence of the House of Commons, and the Queen sends for that person.

The 1919 Paris peace conference had profound consequences

"And the second is that the monarch is not politicised. There is a drill for that in a thing called the Cabinet Manual. It is written as though it is bureaucratic porridge but there is pure gold in there."

But he went on to say that we may be getting used to a more continental way of doing politics, and the markets may not this time threaten to shy at at a little unpredictability.

"If it is seriously hung, if the British people say 'not sure', then it will take longer this time, take longer than five days, partly because Mr Cameron has said if he is involved he will consult his backbenchers first.

"That is bound to take longer. Our system is used to very brutal evictions, but our nervous system is getting used to waiting - and indeed if we are moving into multi-party system, we are going to have to get used to this."

The 2015 election may be without recent precedent, but it may be the one that sets precedents for the future.

The Paris Peace conference of 1919, external following World War One had huge, unforeseen consequences that haunt us to this day.

May 2015 won't be that momentous - but it will reach ahead and weave the future.