A general election that is impossible to call

- Published

UKIP's surge makes prediction nearly impossible

With its first ever prime ministerial debates, new constituency boundaries and opinion polls suggesting the novelty of three evenly-matched Westminster parties, the 2010 general election was difficult to predict.

However, the 2015 election looks set to present us with an even bigger headache.

The great majority of parliamentary constituencies do not change party allegiance in elections.

Therefore, although there will be 650 individual contests in the 2015 general election, the outcome will be determined in a much smaller number.

In 12 of the 17 general elections since 1950, fewer than one in 10 seats changed hands from one party to another.

Even in the massive Labour landslide of 1997, some 70% of seats stayed with the parties defending them.

The killing grounds in any general election - where governments are made or broken - can be found among that minority of parliamentary constituencies - marginal seats - with a history of being won or lost by parties.

There is no fixed definition of a marginal: but if we choose to define them for the 2015 election as seats with majorities of 10% or less that require a swing of 5% for the incumbent party to lose, then there are currently 194 such marginal seats in Britain, of which 82 are Conservative, 79 Labour, 27 Lib Dem, three SNP, two Plaid and one Green.

Marginal seats are not evenly spread: within England, 15% of seats in the South East have majorities of 10% or less, compared with 51% in the South West. In Scotland, 19% of seats fall into this category, compared with 45% in Wales.

Main party support falling

Why is 2015 so difficult to predict? In the 2010 general election, some 12% of voters did not support the Conservative/Labour/Lib Dem parties.

In 18 opinion polls published in December 2014, that figure had more than doubled to an average of 26%.

Lib Dem support collapsed after they went into the coalition government

Since 2010 we have seen a collapse in support for the Lib Dems and the rise of UKIP and the SNP and, to a lesser extent, of the Greens.

If we are to consider the next general election we have to start with the previous one because elections only make sense if we understand what happened when parliamentary seats were last fought.

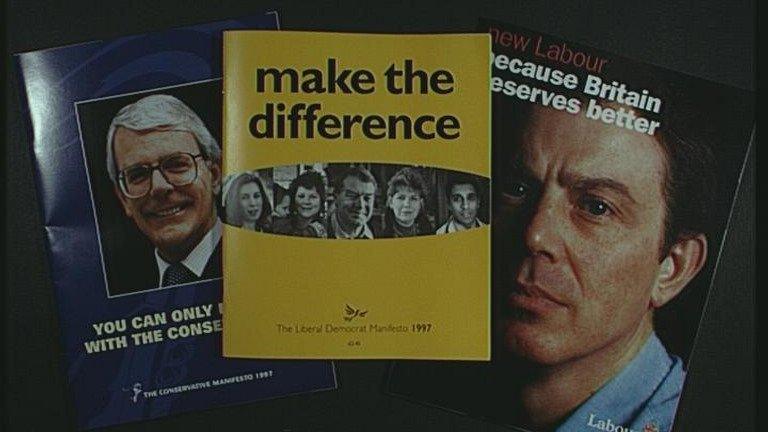

And 2010 was the Losers' Election - the Conservatives failed to win for the fourth general election in a row (the last election when they won an outright majority was in 1992).

GENERAL ELECTION 2015

Labour received their second-worst share of the vote in 80 years; and the Lib Dems, whilst holding their vote share, lost seats.

Where did all that leave us? On 7 May 2015, the Conservatives need a 2% swing to win a majority; Labour need a 2% swing to become the largest party in the Commons and a swing of 5% to win an outright majority.

Historically swings of 2% are par for the course in post-war general elections. Swings of 5% or more have occurred three times in the last 17 general elections.

Post-May 2010, the Lib Dems began to lose support very quickly - down to an average of 12% by December 2010 - half the support they received in the general election only eight months earlier.

Conservative support held up for quite some time but started to drift downwards in the polls from the beginning of 2012.

Labour recovery

Labour's fortunes were much more interesting and surprising.

Following their disastrous performance in the 1997 general election, how long did it take the Conservatives to reach a monthly average of 40% support in the polls? Nine years.

Following their disastrous performance in the 2010 election, how long did it take Labour to reach the same monthly poll average of 40%? Nine months.

Labour's extraordinary recovery was due to the early collapse in the Lib Dem vote, as hundreds of thousands of 2010 Lib Dems, horrified that their party had gone into coalition with the Conservatives, switched to Labour.

2010 Lib Dems currently account for about one fifth of Labour's support in the opinion polls - what the political analyst John Curtice has dubbed "Labour's Crutch, external".

The rise of UKIP has badly damaged the Conservatives.

Currently, around 40% of UKIP's support in the polls comes from 2010 Conservatives - what I have dubbed the "Conservative wound".

In the opening weeks of 2015, the opinion polls put support for Labour and the Conservatives as close, with Labour most often narrowly ahead.

The Lib Dems generally languish in single figures, regularly outperformed by UKIP and with the Greens snapping at their heels.

In Scotland, the SNP dominate the political scene and defy Labour to catch up.

Economy will be key

What issues will dominate the months ahead?

Natalie Bennett's Greens could have an impact

The economy was displaced by immigration as the most important issue facing the country last summer but many voters think that none of the main Westminster parties have any convincing solution to it.

On the question of managing the economy, the Conservatives regularly lead, external Labour.

However, the majority of voters do not feel they are sharing in any UK economic recovery.

And this is where Labour's cost of living agenda, external may gather traction between now and polling day.

We have also seen a significant rise in concerns about housing, low wages and poverty since the 2010 election.

The statutory 2015 election campaign will be one of the longest in living memory - at least six weeks in duration.

The Conservatives are sure to outspend Labour: the latter (carrying debts of £12m already) are relying on out-gunning their opponents with staff and volunteers on the ground.

The Lib Dems hope to hang on to many more of their seats than their current standing in the national polls would suggest.

Not politics as usual

However, a large cuckoo has crash-landed into the Westminster nest and it is noisily disrupting any prospect of politics as usual.

UKIP may not win more than three or four seats but the polls suggest the party will win more votes than the Lib Dems.

The 2015 general election is going to be an angry one and will be a devil to predict.

How will we accurately assess the 2015 prospects for UKIP when the party received only 3.2% of the national vote in 2010 and lost their deposit (i.e. received less than 5% of the vote) in 459 of the 558 seats they contested, reaching double percentage figures in just one seat?

If the economy has been improving for months, why have the coalition parties received no benefit?

Will Labour be shredded by the SNP in Scotland? Will the Greens bleed votes from the Lib Dems and Labour?

Much may change over the next four months but time is fast running out for the current log-jam in UK politics to be cleared in order for a decisive winner to emerge.

- Published20 January 2015

- Published25 February 2015