Another hung parliament? Four scenarios that could follow

- Published

It's Friday 8 May, the day after the general election. The votes have been cast and counted, and a clear picture has emerged - the UK will have a second successive hung parliament.

The question on everyone's lips: What next?

This is the challenge the BBC's Newsnight has set four political commentators, giving each a different election outcome and asking them to envisage what might happen if the results came true.

Here, they imagine how the political landscape may change given such fictional scenarios:

Rafael Behr, The Guardian

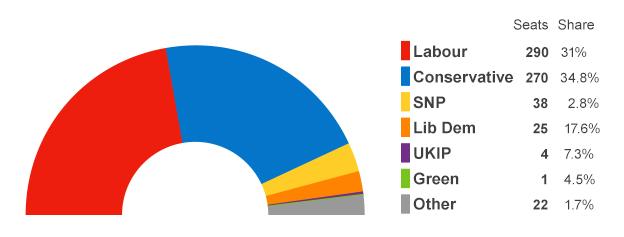

The scenario given to Rafael Behr sees Labour gain 20 more seats than the Conservatives, with the Lib Dems down from 57 MPs in 2011 to 25 in 2015.

In the early hours of Friday 8 May it looked as if David Cameron might still cling on - after all, it is his right as the incumbent to have first go at putting a government together.

But the arithmetic was against him. Tory backbenchers were already talking openly about joining UKIP.

Boris Johnson, the newly elected MP for Uxbridge, said David Cameron had been "neutered by numbskulls and the numbers". And it was true - by the end of the day the prime minister had resigned.

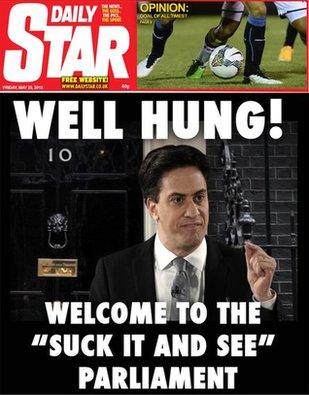

Two weeks passed between election night and the moment Ed Miliband stood on the steps of 10 Downing Street.

He had negotiated what he called "an alliance for change" - not a formal coalition, but an agreement in principle by the Liberal Democrats, Greens and Scottish Nationalists to support a "progressive government" on a case-by-case basis.

This was an arrangement newspapers started calling "suck it and see", while the Independent ran the headline "Green there, done that!", as the Green's MP for Brighton Caroline Lucas was offered the role of climate secretary - announcing an immediate moratorium on fracking.

For the SNP, renewal of the UK's nuclear deterrent, Trident, was put on ice.

So, if the alliance held, Miliband would have a majority of 29. But it didn't.

Since Labour took just 31% of the vote - second to the Tories on 35 - newspapers started referring to the new government as the "League of Losers".

Soon there were demonstrations, and on social media badges appeared saying "We are the 69%" - the percentage of people who had never even voted for Miliband.

Nick Clegg stood down as Lib Dem leader to accept a role as chair of a new Constitutional Convention, but he soon clashed with Foreign Secretary Douglas Alexander when he claimed relations with the EU as part of his new job.

SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon threatened to withhold support for a Labour budget when Chancellor Ed Balls refused to consult her on spending in Scotland.

Newly chosen Conservative leader Boris Johnson tabled a no confidence vote and called for MPs to end the "mathematical monstrosity of moribund Mili-minority".

The Lib Dems split, the SNP abstained and in the end it was 30 despairing Labour rebels who brought their own government down.

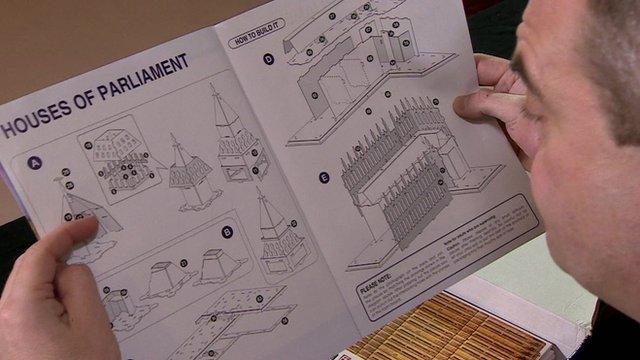

Under the Fixed-Term Parliaments Act, the parties have a fortnight to hold negotiations on a new coalition. Otherwise, there's a second election.

Quentin Letts, Daily Mail

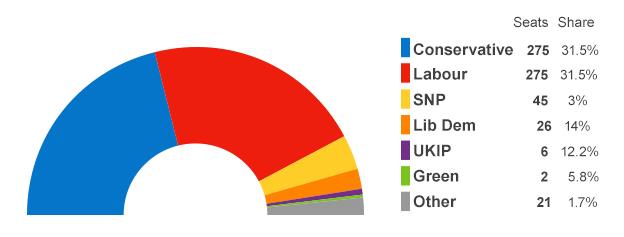

The scenario given to Quentin Letts sees the Conservatives and Labour on an equal footing, with the SNP gaining 45 seats.

Yes, Labour's collapse in Scotland had been predicted, but it was still a jolt to see Alex Salmond standing alongside Prime Minister Ed Miliband in the Downing Street garden that May morning.

The deal? A Scottish independence referendum for the SNP. And for Labour - power.

Deputy Prime Minister Salmond - now Westminster leader of his Edinburgh-based party - looked very much the senior partner alongside a blinking, stammering Miliband.

And here was the big question now dominating politics: Who runs Britain - England or the Celts?

A mini-coalition with Plaid Cymru, the SDLP and Sinn Fein made the SNP kingmakers. They were never going to side with the Conservatives.

The end game for the SNP remained the break-up of the UK, but some nationalists feared going into coalition with Labour would dilute their identity as separatists.

A source close to Mr Salmond described the wider goal - infuriate the English so much that they want to end the union. "Nats the way to do it," ran the Scottish Sun.

Full of bravado, Mr Salmond swaggered up Downing Street and announced outside the door of No 10: "It was the Jocks wot won it."

Interrupting Ed Miliband at the press conference, he said: "The English bossed us around for 300 years, now it's our turn."

At an occasionally violent rally in Wembley stadium, the Tories - led by Theresa May - and UKIP demanded a referendum on English independence. The Queen begged English voters to "think very carefully" about any breakaway. Financial markets were jittery.

Meanwhile, from Dover House - Whitehall residence of our new deputy PM - there came the sound of bagpipes, Scottish reels and the melodious baritone of Alex Salmond.

Isabel Hardman, The Spectator

The scenario given to Isabel Hardman sees UKIP gain 6 MPs, while the Conservatives amass 17 more than Labour.

UKIP's ability to secure six seats on the green benches was a feat unimaginable not all that long ago, and in the early hours of that May morning chaos reigned.

Tory backbenchers weren't happy, and the drawn-out nature of the Conservative-Lib Dem negotiations had left David Cameron's critics with plenty of time to launch their own campaigns against him.

Nick Clegg's demand for 50% representation on the Quad - the top decision-making committee in government - took up five full days of horse-trading alone.

After three weeks, we finally had a government. Cameron insisted that all members of his Cabinet appear on TV to put their names to the new agreement.

What helped them was the bloody ejection of Ed Miliband after Labour's abject failure. The new king? Chuka Umunna.

"Over the Umunna," ran The Mirror's front page. "Red Ed Dead," went The Sun. And Guardian polls showed Nick Clegg's popularity was still not getting any better.

The knives were sharpened for Clegg, but after surviving a botched leadership bid from Vince Cable he once more became deputy prime minister as the Lib Dems ended up with 10 ministers.

Clegg continues to chair the cabinet committee on home affairs, which he uses to block all policies he doesn't like.

But this isn't a coalition governing by majority. It is a minority government, relying on UKIP to deliver budgets and other key votes. The price for that? A 2016 EU referendum.

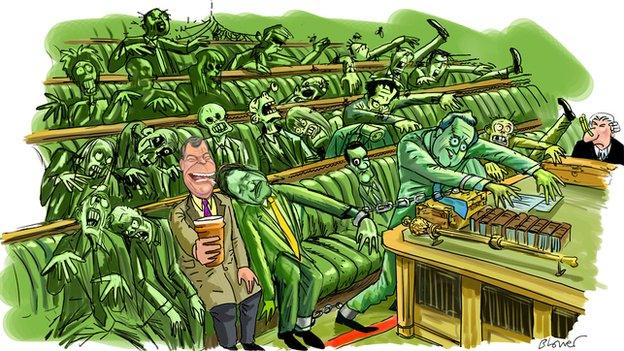

No-one expects it to last very long or produce much in the way of big reforms. But unless all the parties involved in government vote to end it, the Fixed-Term Parliaments Act means the lifeless Con-Lib government - propped up by the kippers - lurches on.

What this strange new government will achieve while it lasts is anyone's guess. But if you thought the last government ran a zombie Parliament, just wait until you get a load of this one.

Helen Lewis, New Statesman

The scenario given to Helen Lewis sees Labour lead the Conservatives by 23 seats, while the SNP amass four more than the Liberal Democrats.

By the morning of Friday 8 May, Ed Miliband knew that either the Lib Dems or the SNP could deliver him enough seats to pass a budget. So should he go tartan, or yellow?

Trying to dodge a hungry press pack, it was over a sausage and egg supper at an M1 service station that Alex Salmond and Mr Miliband met to thrash out a deal.

But as the Labour leader emerged from the rendezvous it was clear that the SNP's leader at Westminster was asking for too much. Miliband wouldn't give up Trident, and he refused to strengthen his rivals by giving them even more tax powers in Scotland.

So he moved on to a dinner date with Nick Clegg. There was plenty for their parties to agree on - Lords reform, higher property taxes, votes at 16.

The sticking point was the men's frosty personal relationship. There was only one thing for it - Nick Clegg sealed the Lib-Lab coalition, and promptly fell on his sword.

This meant a rather steep elevation for former party president Tim Farron, who went from backbencher to Lib Dem leader and deputy prime minister in one fell swoop.

Elsewhere, in the defeated Tory party it was all-out war. Backbenchers rounded on their leader and the shadow cabinet imploded. "Eton Mess: Tories turn on one another" was the Telegraph's headline.

As David Cameron returned to Oxfordshire to stick the kettle on, Boris Johnson took on Theresa May for the party's leadership.

After a bruising battle, Boris emerged victorious - but his reign over the Tory party only lasted six months, until the Mirror's astonishing scoop over his unfortunate incident with the bicycle pump in the nunnery.

Ed and Tim embarked on a somewhat familiar feeling programme of sweeping changes - another NHS reorganisation, withdrawing benefits from migrants, tough cuts to get the deficit down.

And so, within a year of the 2015 election, the new Tory leader George Osborne was facing Ed Miliband across the despatch box.

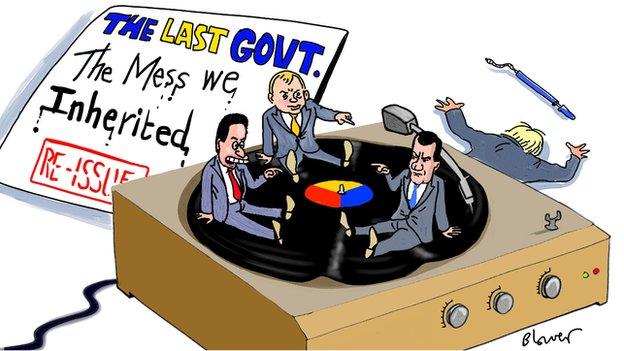

As the Labour leader blamed the new economic crisis on "the mess we inherited", voters wondered whether anything had really changed at all.

Analysis: Allegra Stratton, BBC Newsnight Political Editor

George Osborne likes to quote Lyndon B Johnson's first rule of politics: It's "practitioners need to be able to count."

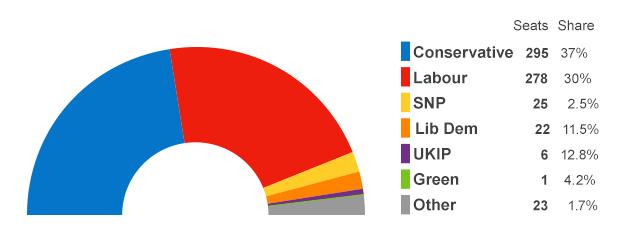

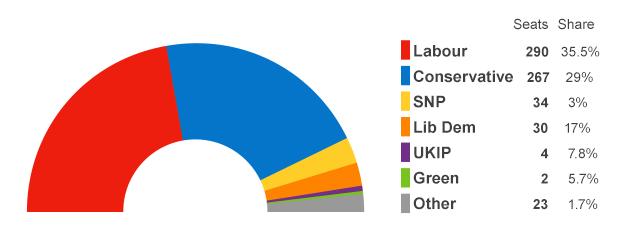

These days I have a lot of conversations in Westminster's Portcullis House that go like this: "The Tories lose 30 seats to Labour, get 15 off the Lib Dems and lose one to UKIP - which puts them on 290ish. Labour lose over 20 to the SNP.

"Lib Dems get 30 seats, go back in with the Tories - that equals 320. With the DUP's 8 MPs they are over the magic 326 [the number of MPs needed for a majority]."

The next conversation runs the numbers another way entirely: "Labour win 50 seats off the Tories and 15 from the Lib Dems..." and so on. A Beautiful Mind it isn't, but it's still more maths than Marx.

It remains possible that between now and the general election - some 100 days away - there is a march back to the mainstream. That one of the two main parties breaks away from the other, with closer to 40% of the electorate planning to vote for them than 30%, as the public start to form a firmer idea of which they'd like to run the show.

But we aren't there yet. Opinion polls show Labour and the Tory party edging along next to each other - crowded around a 32%, 33%, 34% low-water mark, only yielding each of them around 290 seats.

So how to get over 326 MPs - or 323 if you factor in that at the moment the five Sinn Fein MPs don't take their seats?

Opinion pollsters agree that if the polls stay where they are, three parties - not just two - may be needed to form a majority government.

Newsnight broadcasts Monday to Friday on BBC Two, from 22:30 GMT.

- Published12 January 2015

- Published2 January 2015

- Published23 January 2015