The challenges of staging a seven-leader debate

- Published

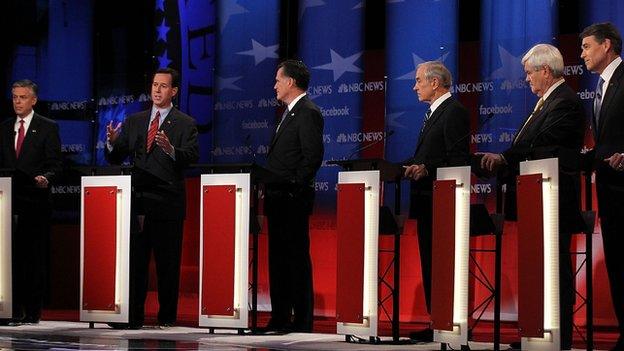

Multi-party debates are common during the US primaries, where presidential candidates are chosen

Fans of the Danish political drama Borgen will be familiar with election TV debates featuring a string of politicians standing at podiums on a stage.

Indeed, in the very first episode of the series, the heroine, Birgitte Nyborg, leader of the Moderates party, has a game-changing moment during a debate involving seven party leaders.

The drama is based on real-life Danish politics with its multi-party system, where such debates are an established feature of elections.

Multi-candidate debates also take place in several other countries, particularly those where coalition politics is the norm such as Germany and the Netherlands.

In the US, TV debates during the primaries can feature eight or nine hopefuls on a stage - though the actual presidential debates resemble gladiatorial head-to-heads between the two main parties' candidates.

The idea of staging a seven-way TV debate in a real-life British election, however, is completely new territory, yet that is now what is happening.

The ITV debate on Thursday involves not just the Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat leaders, as in 2010, but also UKIP, the Green Party plus the nationalist parties of Scotland and Wales - the SNP and Plaid Cymru.

Debate details

The debate will be shown on ITV from 20:00 to 22:00 BST

It takes place at Media City in Salford with a studio audience of about 200 people

After a draw for podium places, the Green Party's Natalie Bennett will take the left-hand position followed, from left to right, by Mr Clegg for the Liberal Democrats, UKIP's Nigel Farage, Mr Miliband, Plaid Cymru's Leanne Wood, SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon and Mr Cameron

Ms Bennett will speak first in the opening statements of the debate while Mr Cameron will speak last

Each leader will be allowed to give an uninterrupted one-minute answer to questions posed by members of the studio audience

There will then be up to 18 minutes of debate on each question; in all four "substantial election questions" will be addressed

Leaders will not see the questions in advance and an "experienced editorial panel" will select them

It's a complex format to make work.

Firstly, there is a practical challenge: how to create from them engaging television which entertains as well as informs and which, crucially, the politicians will accept.

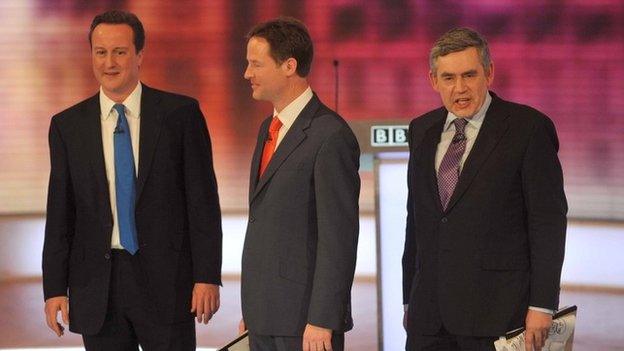

In 2010, the BBC's chief political adviser Ric Bailey helped negotiate the debates on behalf of the broadcasters.

The 2010 debate format involved months of "detailed wrangles" according to the BBC's Ric Bailey

In an academic paper he wrote for the Reuters Institute, external, he described "long winter months of hammering out a suitable format" as the broadcasters "sought the appropriate territory somewhere between frivolous and dull".

The format they came up with involved allowing the three party leaders to give set-piece statements outlining their positions as well as time for spontaneous debate where they engaged with each other.

Staging something similar in 2015 with seven leaders presents a significant challenge.

"There is a simple danger which is that for every single question, you would have to have a number of standard answers from all the candidates where everyone goes for the median voter and tries not to upset anybody who's undecided and the end result is boring," says Professor Stephen Coleman of Leeds University, an expert on TV debates.

'Fifteen to One'

Whatever format is agreed, the broadcasters have to abide by regulations to ensure fairness and balance for all participants while also avoiding the risk, argues Paul Waugh, editor of the PoliticsHome website, of producing a turn-off.

"There's a danger of the debates resembling a 'Fifteen to One' for political nerds," he says.

"The whole point is supposed to be about engaging voters in politics. If they tune in to a string of politicians presenting prepared statements with no time for interaction and debate, they may well switch off."

On the other hand, says Professor Stephen Coleman, another scenario could emerge from the multi-party format.

"What may happen is the candidates realise that with more people it's more difficult to make a big impression and they try to be outrageous and break the rules in order to stand out. That could create some dramatic moments.

"TV debates help voters to focus on the characters of the people on stage and viewers are very good at making judgements on that basis. They watch for the body language, the cringe moments or the funny moments.

The TV drama Borgen included agenda-changing election debates

"If there are more people it's harder to carve out a presence. That could play well to the strong personalities."

Whatever is decided, argues Professor Coleman, the task ahead for the broadcasters is "very very difficult".

International experience may not provide much in the way of reassurance. After years of staging multi-participant debates, the Dutch broadcaster NOS has ditched the format for this year's regional elections.

In its place will be a lottery system in which names for head-to-head debates will, literally, be pulled out of a pot.

"Organising a debate with more than four participants is a hell of a job. Putting them all together in one discussion really wasn't working very well," explained editor-in-chief Bram Schilham on BBC Radio 4's Today programme.

National nuances

Another factor which presents a challenge is the inclusion of the SNP and Plaid Cymru in the format. In 2010, there were separate debates for the main party leaders in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Some have questioned the inclusion of parties which aren't represented across the UK.

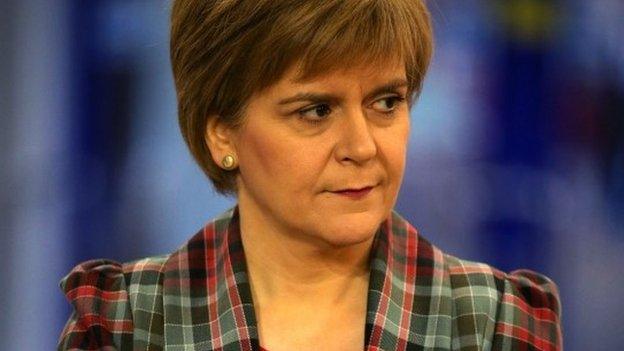

Nicola Sturgeon will be included even though the SNP does not field candidates outside Scotland

"It's a problem," argues Paul Waugh of PoliticsHome. "Many viewers in England may not be interested in what's happening in Scotland and Wales and confused about why they're watching people they couldn't vote for if they wanted to."

"When it comes to the nuances of which policies are devolved and which aren't, many will simply be lost."

Professor Coleman says it is difficult to predict the effect of including the SNP and Plaid Cymru.

"People in England may be genuinely interested in what these parties have to say and may be attracted by new figures, feeling that they've had enough of seeing Cameron versus Miliband," he says.

"Or it could reinforce a feeling of fragmentation. We genuinely don't know."

He said the debates as a whole could be "awfully bland" but added: "There's so much that will be different with this new format. For one thing, there will be three women taking part. That's a big change from last time.

"I wouldn't mind having a small punt on the prospect of debates with seven leaders delivering something really new and interesting."

- Published23 January 2015

- Published23 January 2015