Net loss: Anatomy of a pledge

- Published

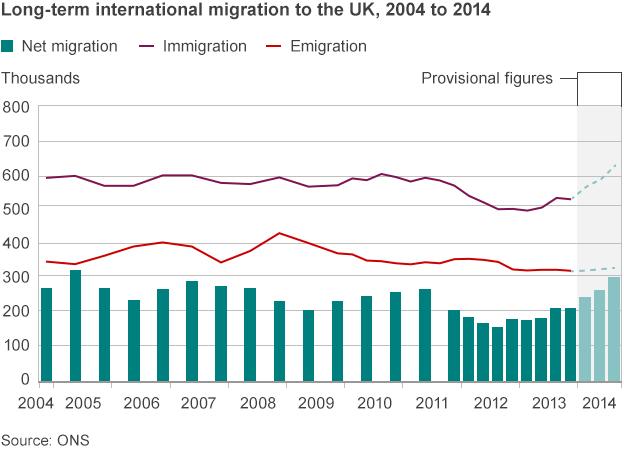

David Cameron's pledge to cut net migration to under 100,000 year has been blown out of the water by the latest set of figures. But why did he make such a promise in the first place?

A policy is born

David Cameron announced the new approach in 2007

The Spectator's political editor Fraser Nelson claims it was all an accident.

"The pledge originated in a Thick-of-It style farce: it was an aspiration mentioned by Damian Green, then immigration spokesman, that caught media attention," he writes in a blog on the Spectator website., external

"The Tories didn't want to make a fuss by disowning it, so this pledge ended up becoming party policy and then government policy."

Countries can only control who comes in, not who goes out, so attempts to cut net migration are always doomed, critics say.

The Conservatives fought the 2005 election on a pledge to "set an overall annual limit on the numbers coming to Britain".

The Conservatives' 2005 election campaign was branded racist by Labour

But when Mr Cameron took over the Tory reins after Tony Blair won a third term for Labour, he wanted to end talk of immigration quotas, which had led to accusations of racism.

He argued that what people were really worried about was not immigration, which could be good for the economy, but population growth, which increased pressure on public services and threatened community cohesion.

In a speech in 2007, external, he announced it was "time for a change".

"We need policy to reduce the level of net immigration."

No one had really done this before.

But Mr Cameron insisted it was possible if you brought in tighter curbs on non-EU migration - something he had control over, as opposed to movement within the EU, which he didn't.

The numbers game

Damian Green was the shadow immigration minister

So where did the 100,000 figure come from?

When he was asked in the run up to the 2010 election, Damian Green - who always acknowledged it was difficult to control net migration precisely - liked to talk about returning to the levels of population growth seen in the 1980s and 1990s.

It never sounded like a hard and fast pledge, more of an aspiration, even when it appeared in the 2010 Conservative manifesto: "We will take steps to take net migration back to the levels of the 1990s - tens of thousands a year, not hundreds of thousands".

That was normally hardened up to below 100,000 in headlines.

That sounded more like a pledge.

'No ifs, no buts'

David Cameron turned an aspiration into a promise

The "tens of thousands" target was left out of the coalition agreement with the Lib Dems, which said there would be an "annual limit" on non-EU migrants.

But Mr Cameron and Home Secretary Theresa May did not let it drop.

In a speech in 2011, which may come back to haunt him during this year's election campaign, Mr Cameron said he would hit his target "no ifs, no buts," adding "that's a promise we made to the British people and it's a promise we are keeping". At that point, it looked as if they could deliver.

Lib Dem opposition

Business Secretary Vince Cable was against the net migration target from the off, stressing that it was a Conservative policy not a coalition one.

Businesses hated it, he argued, because they could not bring in the highly-skilled workers from India and the US that they needed. And the universities hated it because it restricted the lucrative flow of foreign students.

And, pointed out the veteran Lib Dem, it did not make any sense as a pledge because it could be blown off course by a sudden increase in Brits emigrating, which happened from time to time.

Mr Cable even claimed Mr Cameron "risked inflaming extremism".

Early success

At first it looked as if Mr Cameron might hit his target. Immigration began to fall during 2011, with policies such as a crackdown on "bogus" colleges, rationing non-EU visas and a minimum income threshold of £18,600 for anyone planning to sponsor a non-EU family member, such as a spouse, to come to the UK.

The numbers turn

The ongoing economic crisis in the eurozone led to a sharp increase in unemployment in southern EU states, such as Spain and Portugal. Workers began to head to the UK in search of work.

At the same time, the "transitional controls" on Bulgaria and Romania, seen by Mr Cameron as a key lever in controlling migration, were coming to an end.

Theresa May and her Home Office ministers continued to insist that the target would still be met. But it became a tougher task with every passing quarter, as net migration began to head back to levels seen before the 2010 election.

The dam breaks

November 2014 was when the game was really up. Theresa May was forced to admit, on the BBC's Andrew Marr programme, that it was "unlikely" that the target would be met. Net migration had soared to 260,000 - higher than when the coalition came to power.

Die-hards, or hopeless optimists, could possibly dream that the next set of figures - the last before the general election - would start to head downwards again.

A big increase in immigration from outside the EU put paid to that.

What about the future?

The latest figures are for the year ending September 2014. So it is possible that net migration levels are falling as we speak. Possible but highly unlikely.

The chances are they will continue to climb, as the UK economy continues to outperform the eurozone.

Mr Cameron is said not to be too upset about this - despite the fact that it is a gift to UKIP - because it is a sign of economic success.

But a broken promise can still be a terrible thing for any politician to have to deal with, particularly in an election year.

Nick Clegg, who has had his own difficulties with broken pledges, was among the first to put the boot in when the figures were announced.

Mr Cameron's official spokesman declined to comment on whether he would repeat his pledge to reduce immigration to "tens of thousands", but said the effort to reduce numbers was "going to be a challenge for the next parliament".