Election 2015: How close are you to the political centre?

- Published

There is a particular piece of hallowed turf which all politicians like to think they are standing on. It is a Goldilocks place where everything seems just right, where their views and the people's coincide, where harmony rules.

It is a place where elections are won, and as we enter the final straight to the 7 May election, all political leaders seem to be stampeding for the spot. They call it the centre-ground.

But according to new research, based on the British Social Attitudes survey, the centre ground is always moving.

How close are you to the political centre?

Answer the five official survey questions below - asked almost every year since 1986 - and see how your views compare to the rest of the population. You will find out how close you are to the current political centre or whether you are a closer match to the 'centre' in previous years.

The results don't imply you should vote for any particular party - instead they reflect where you stand on economic issues compared to the rest of the British population, as surveyed by NatCen Social Research.

Try the quiz

Users of the BBC news app tap here, external to take a quiz that will tell you how close you are to the political centre-ground.

Tony Blair was someone who found the centre ground - that political sweet spot - and pitched his party's tent firmly on it in 1997.

"It's a vision which is right in the centre-ground of British politics today," he told a crowd in Manchester back then. "And if it has one value at its core, it is the simple British value of fairness."

Fast forward to 2015, and his successor, Ed Miliband, claims he is occupying the same piece of priceless political real estate.

"We're a party firmly in the centre-ground of politics," he said in January. "And this is where I think the centre-ground is: people want a society where, yes, people who do well are properly rewarded, but also where there is fairness."

But wait, because David Cameron says he has already raised his flag there.

"The real common ground, the real centre-ground of British politics right now, is who has got the answers to making sure Britain competes and succeeds in the global race? That's the question which wasn't answered by Labour, which is being answered by us," he told the BBC last year.

Mr Cameron, Mr Clegg and Mr Miliband all claim to occupy the centre ground

And who is this, who is also staking his claim to the Elysian Fields of centre-ground politics?

"We are the only party able to build a stronger economy and a fairer society too. Liberal Democrats: take this message out to the country - our mission is anchoring Britain to the centre-ground," Nick Clegg told his party conference in 2013.

The centre-ground is starting to look awfully crowded. And surely they cannot all be standing on the very same spot?

This election season is different because we have insurgent parties of the right - UKIP, and the left - the Greens and SNP, who seem to be shaking up the old political order. But all successful politicians know that in our political system, elections are actually won in the centre-ground.

So the crucial question is this - where is the centre?

Research suggests public attitudes are currently moving toward the left, politically

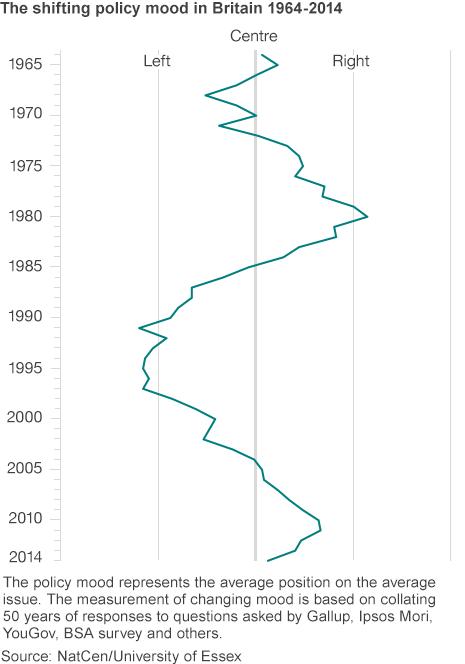

A new analysis by academics at Essex University, using more than a thousand pieces of polling and survey data, has tracked the political centre over the last 50 years.

They have done this by mapping public attitudes to a wide range of issues such as tax and spending, welfare, business, the monarchy, and abortion and placing them on a left-right scale.

Much of the data comes from the annual NatCen British Social Attitudes survey which has been tracking public attitudes for more than 30 years. Next week NatCen is publishing the results of the 2014 survey.

And here is the thing: the political centre - where, en masse, the views of the electorate generally coincide - is, as already mentioned, always moving.

No wonder politicians spend so much time looking for it.

It is currently moving leftwards politically, according to the research. It has been heading in this direction since the last general election in 2010.

And here is the other thing: it always moves in the opposite direction to the policy programme of the government.

In 1979, a milestone year in British politics, the data shows that the political centre was at the most right-wing point it has ever reached.

But as soon as Margaret Thatcher was elected, the centre started reacting against the direction of policy by moving to the left, and continued to do so until the mid 1990s.

Although the voters were moving leftwards, the Labour Party was seen as even further left, and it was not until 1997, when Tony Blair had abandoned the extremes of left-wing Labour policy and moved his party to the centre, that they won.

But no party can afford to rest there in the centre-ground, because it does not stay in the same place for long. In 1997 it started moving rightwards and continued to do so until 2010, when the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition won power.

"The electorate tends to move in the opposite direction to the policy trajectory of the incumbent government," Dr John Bartle told politics students at Essex University, as he presented his research.

"If Labour are in power and they increase public spending; that will shift the electorate to the right. If the Conservatives are in power and they reduce public spending and they reduce average tax levels; that will drive the electorate to the left."

Tony Blair moved his party from left of centre, to the British centre-ground, according to Peter Kellner

One of the students spotted the quirkiness of the findings. "It seems very counter-intuitive," said Franklin Murray. "You'd expect that if parties promised certain policies and that's what they were voted in for, and then performed on them, that the electorate would be satisfied."

Instead it seems, oddly, that by delivering on their programmes, parties sow the seeds of their own destruction.

Some political scientists have described the centre-ground as like a thermostat. If things get too hot under Labour - too much government - the centre wants to cool things down and move to the right.

Equally, if things are too cold under the Conservatives - inequality rises for instance - then the centre moves left to a warmer policy of more welfare.

So when parties hit that sweet spot on the centre-ground, why do not they just stay there, and keep in tune with the electorate?

"Most voters are in the centre-ground. Most party members and most MPs are not," Dr Tom Quinn, one of John Bartle's colleagues at Essex University, told BBC Radio 4's World at One.

"When you see parties which track closely to the centre-ground like Blair's New Labour, it causes internal tensions. So there were always problems between Blair and the trade unions, and Blair and the Brown-ites. When David Cameron moved the Conservatives to the centre it caused problems with the Conservative right.

"So a party might do what it needs to do in order to win an election, but once it's in government some of its supporters might see it as time to start delivering on its core ideological promises. So there's always a temptation to start catering for those less centrist elements."

Margaret Thatcher's electoral victory in 1979 marked a turning point in British politics, says Peter Kellner

Britain has a particularly rich set of data to work from going back more than 50 years, but similar analysis has been done in other countries such as the US, Canada, Germany, France and Spain. In all these countries the same model seems to apply, according to the researchers.

Most of the time the political centre is moving in opposition to the government of the day, but sometimes a strong political leader can actually shift the political centre by successfully persuading the public that a new paradigm is needed.

Peter Kellner, the President of YouGov, is a veteran political commentator and pollster. He believes this is why 1979 was such an important year in political history because of the political chaos earlier under Labour and the subsequent actions of Margaret Thatcher.

"She might have suffered from being right wing, but what she managed to persuade people was that there was a new sensible centre-ground which happened to be to the right of where British politics had previously been," he said.

"In that sense Margaret Thatcher was more of a game changer than Tony Blair because she explicitly moved the centre - and the fact that her reforms were accepted by Tony Blair demonstrates that."

"Tony Blair though did not move the centre. He accepted the centre he bequeathed and took his party to that territory."

So what are the lessons for the 2015 election?

If the current centre-ground is moving leftwards, it ought to benefit Ed Miliband and Labour. But Ed is not ahead.

The last time the political centre was at this point on the left-right scale, in 2005, Labour won the election with a working majority. The polls suggest Labour will struggle to achieve this in May.

"The policy mood has moved left, but Labour needs to make sure it hasn't moved even further to the left. It can only take advantage if it stays in the centre," said John Bartle.

"But," he added, "Labour has another more serious problem. And that is perceptions of its competence. The Labour Party lost its reputation for economic competence in the period from 2008 to 2010."

And Peter Kellner believes that Ed Miliband's problems are also more personal.

"David Cameron is seen as further away to the right from the centre than Ed Miliband is to the left. And yet David Cameron is regarded as a far more capable leader."

The 2010 election resulted in the first coalition since World War Two

He adds: "The left-right axis is only one of a number of judgements that people make. They're also making a judgement on the basis of competence and character, and Ed Miliband loses more on this than he gains by being closer to the centre."

Those behind the research also believe that it vindicates our democratic model. They say because the policy mood is almost always moderate, it punishes politicians who become too extreme.

"In this democracy you really do govern," said John Bartle. "You as an individual are irrelevant, but collectively the electorate does ensure that government overtime, broadly speaking, pursues the policy direction that the electorate wants."