How are the proceeds of crime recovered?

- Published

Between 2010 and 2014, more than £746 million in criminal assets were recovered, according to the Home Office

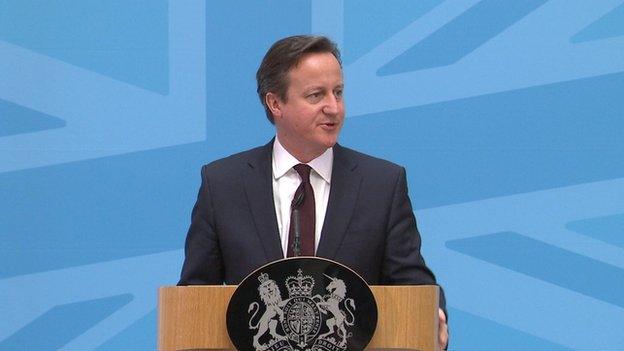

The prime minister has announced new plans to seize the wages of illegal workers as proceeds of crime as part of a new immigration strategy. But how does the UK go about recovering the proceeds of crime, and what challenges might the new plans throw up?

What counts as the "proceeds of crime"?

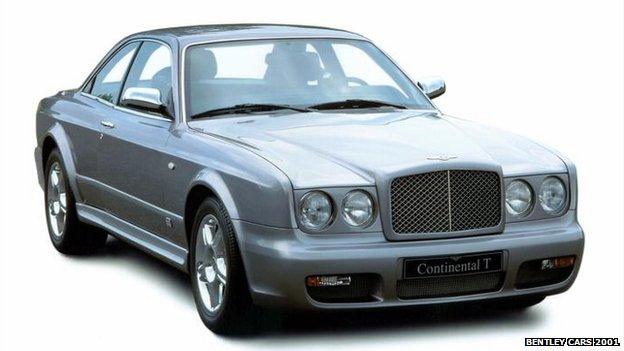

A Bentley Continental was among cars seized by the Met under the Proceeds of Crime Act in the last five years

Any money earned as a result of, or in connection with, an offence can be recovered under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

That also includes assets bought with the proceeds of crime - a red Ferrari and a Bentley Continental car, jewellery, watches and properties within London and the Home Counties are among assets recovered by the Metropolitan Police in the last five years.

Previously, if a person gained a job by deception - for example using a fake passport - any money they earned in wages might be considered proceeds of crime, and therefore eligible for confiscation.

However, people in the country illegally, but who had not obtained a job by deception (for example if their employer knew they were here illegally), would not be pursued for their wages.

The government plans to create a new offence of "illegal working" to change that.

How are the proceeds of crime recovered?

Seizing the proceeds of crime is one way the police target organised crime

Simply speaking, there are two ways that the proceeds of crime can be reclaimed.

Firstly, anyone convicted of a crime can be ordered to pay. The court would calculate how much they were required to hand over, and a person might face prison if they failed to pay.

Secondly, the police can seize £1,000 or more cash on the spot if they have reason to think someone might have earned it through illegal activity. No criminal conviction is required.

A court would then decide whether that money was indeed earned from criminal activity, and whether it should be forfeited permanently.

The UK authorities can still go after people's assets even if they are abroad, for example by asking the overseas jurisdiction to freeze or sell them.

Where does the money go?

A martial arts academy in Wales is one community project that has been funded from cash recovered from criminals

The police are able to claim some of the confiscated money and assets back to reinvest into policing, through an incentive scheme.

For confiscations of assets rather than cash, the Home Office gets half and the other half is spilt equally between the police, the Crown Prosecution Service, and the courts.

Where cash is seized, the Home Office gets half and the police get half.

In some cases, a judge can decide to award a percentage of any confiscated money to the victims of crime as compensation. There have also been schemes where seized money has been given to community schemes.

How effective is the law?

"Canoe frauder" John Darwin, who faked his own death, was ordered to pay £679,073 that he earned from his crime

The Metropolitan Police argues that being able to confiscate the proceeds of crime acts as a deterrent to "acquisitive criminals", such as burglars, because the risk that their ill-gotten gains will be seized begins to outweigh the potential monetary gains.

Officers also claim it helps disrupt "negative role models who have lots of money but don't work" - and that targeting their assets shows them, and the public, that "crime doesn't pay".

As of December 2014, there were 1,244 live confiscation orders, external under the responsibility of the Crown Prosecution Service, amounting to nearly £500 million, of which 31.5% was deemed "collectable".

According to barrister Will Hayes, who specialises in asset forfeiture, the courts are generally quite successful in recovering the proceeds of crime - but there are challenges.

"Criminals hide their assets very effectively, often overseas, and in some cases jurisdictions might not be very cooperative," he says.

And in some cases, people choose to spend the extra time in prison rather than pay up, he adds.

When it comes to pursuing the wages of illegal workers, he suggests money could prove difficult to recover.

"One would think they're going to be fairly low level modest wages. If you're talking about low sums of money, You've got to think about how much it costs to instruct a lawyer and take something through the courts."

He says there have been some recent successful cases where money was recovered from Eastern European nationals who defrauded the benefits system and bought houses overseas.

But he adds that there must be a "balancing act" to weigh up whether cases are worth pursuing.

- Published21 May 2015

- Published21 March 2013

- Published13 May 2012