Will more free childcare fuel baby boom?

- Published

- comments

The issue of Britain's rapidly growing population tends to focus on just one factor - immigration. But are the "family friendly" policies of successive governments playing a part too?

When German Chancellor Angela Merkel decided to do something about Germany's shrinking population, she boosted the state's financial support for working families and guaranteed a kindergarten place for children aged 12 months or older.

Yet when Britain's political leaders announce "family friendly" policies of their own - such as David Cameron's plan to double the number of free nursery places for three and four-year-olds in England - the potential impact on the size of the population is never mentioned.

Immigration is portrayed as the only factor that matters.

Subsidising nursery care and shared parental leave are seen as popular, vote-winning measures, something that helps new parents who want to return to work and resume their careers. During the election measures were proposed by all the parties with few, if any, voices of dissent.

But do they also encourage people to start families or have more children, increasing the strain on public services?

'Baby boom'

It would be a brave, or foolhardy, politician who tried to advance such an argument in Britain, where every policy pronouncement is talked up as a great boon for "hard working families," whether it helps them or not.

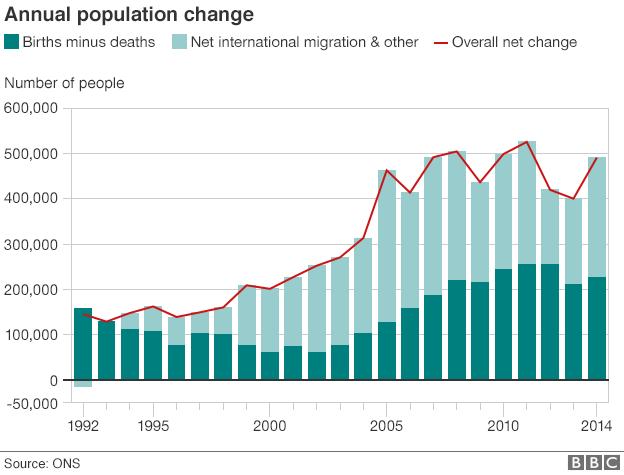

Net migration accounts for just over half of Britain's population growth, with the remainder due to a combination of people living longer and live births, although the gap has grown recently with more new arrivals.

Latest Office for National Statistics figures, , externalfor 2014, released on Thursday, confirm this trend, with the overall number of births down slightly on the previous year. Britain's population grew by 491,100 to reach a total of 64,596,800, the figures suggest.

Tony Blair began the drive for more 'family friendly' policies

There has been a migrant "baby boom" in England and Wales in recent years, with the percentage of births to foreign-born women going up from 16% to 26% of the overall total, in the ten years to 2011.

A new report by the Centre for Population Change, external, suggests one of the biggest factors driving this is "family formation," with women from poorer parts of the world, such as Pakistan and Bangladesh, waiting until they join their husbands in the UK before starting a family. A third of Pakistani and Bangladeshi women had a birth in the first year following arrival, the report found.

Young Indian and Polish women, who are also arriving in the UK in significant numbers, were less likely to have children shortly after arriving in the UK, the research suggested.

But, interestingly, total fertility rates for Polish born migrants in England and Wales - an estimate of how many children they are likely to have in their lifetime - is higher, at 2.1, than in Poland, where it is 1.4.

Fertility rates among UK-born women are also on the increase, from 1.64 births per woman in 2001 to 1.9 in 2012, despite the economic downturn.

Fertility and population growth

If immigration to the UK ended tomorrow Britain's population would continue to grow because people are living longer and recent arrivals from countries such as Poland, India, Bangladesh and Pakistan are boosting fertility rates.

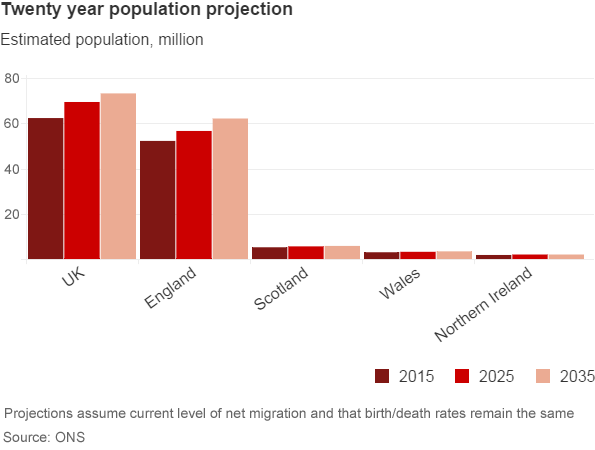

The size of the UK population with no additional net migration would level off at 67.5 million over the next three decades and would eventually decline, according to projections by the Migration Observatory, external. (if migration continues at current levels the population will reach 73.3 million by 2037).

The fertility rate in Britain is still short of the magic figure of 2.1 - the rate at which the population replaces itself.

Jill Rutter, a demographics expert, who works for the Family and Childcare Trust, is wary of linking rising these fertility rates to "family friendly" government policies.

"There are a whole range of factors that affect fertility rates, not just parental leave and free child care - the cost of living, housing prices, gender equality and women's expectations among other things," she says.

America has roughly the same fertility rate as the UK but has no paid parental leave or free childcare, she adds.

'Male breadwinner'

But there is some academic research suggesting a direct link between the amount spent by governments on supporting families and birth rates.

According to 2011 paper, external by US sociologist Ronald Rindfuss "moving from having no child-care slots available for pre-school-age children to having slots available for 60% of pre-school children leads the average woman to have between 0.5 and 0.7 more children".

A report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), from the same year, found that the policies that have the biggest effect on birth rates are those aimed at helping women combine career and family, rather than those trying directly to boost the birth rate, such as paying women to take time off work to have children (something Germany has also tried).

It used to be assumed that women who stayed at home while their husbands went out to to work were more likely to have children than "career women".

Angela Merkel is trying to make life easier for working parents

The opposite has turned out to be true in many European nations, with the highest fertility rates in countries with high levels of female employment, more non-traditional families and family friendly child care policies, such as France and the UK.

Germany, which is periodically gripped by an existential crisis over its birth rates, which have remained stubbornly low, at 1.4, despite relatively high levels of immigration, is different.

It has high levels of full time employment for women but fewer opportunities for women to work flexibly or return to their jobs on a part-time basis, particularly in the West of the country, where the traditional model of the "male breadwinner" still holds sway, and society frowns on women who return to their careers after having children.

East Germany

Dr Andre Wolf, of the Hamburg Institute of International Economics, says German couples "want to have economic security before they are willing to bear children, to create a family" and migrants tend to fall into the same patterns of behaviour.

Attitudes are changing, he adds, but women are still forced to choose between having a family and a career - and their decision is not helped by the shortage of kindergartens in urban areas.

In the old, communist East Germany women were expected to work full time while their children were looked after by state-run nurseries. There is still a legacy of this system in the East where, according to a 2011 paper from the Max Plank Institute for Demographic Research, external, birth rates are now higher than those in the West.

It's by no means perfect for working families in the UK. The cost of child care is high by international standards and there is still a shortage of nursery places in some areas.

And it has never been the stated aim of a British government to boost fertility rates by increasing access to nursery care.

But it is worth bearing in mind, the next time an immigration crackdown is announced, at the same time as a fresh push to help working families, that the two might be pulling in opposite directions.