How did we get to this welfare state?

- Published

We think of the welfare state as a creation of the 20th Century but its roots stretch back to Elizabethan times. It's a history littered with benefit crackdowns, panics about "scroungers" and public outrage at the condition of the poor.

In an 1850 investigation into the life of the poor, Charles Dickens described how the inmates of a Newgate workhouse skulked about like wolves and hyenas pouncing on food as it was served.

And how a "company of boys" were kept in a "kind of kennel". "Most of them are crippled, in some form or another," said the Wardsman, "and not fit for anything."

Dickens sparked outrage with his powerful evocations of workhouse life, most famously in the novel Oliver Twist, but the idea that you could be thrown into what was effectively prison simply for the crime of being poor was never seriously challenged by the ruling classes in Victorian times.

There was no welfare state, but the growth of workhouses had been the product of a classic British benefits crackdown.

Since Elizabethan times and the 1601 Poor Law, providing relief for the needy had been the duty of local parishes. Life was not exactly easy for itinerant beggars, who had to be returned to their home parish under the law, but their condition was not normally seen as being their own fault. They were objects of pity and it was seen as the Christian duty of good people to help them if they could.

But by the start of the 19th century, the idea that beggars and other destitutes might be taking advantage of the system had begun to take hold. The "idle pauper" was the Victorian version of the "benefit scrounger".

'Extortion and perjury'

Dinner time at a workhouse in London's St Pancras, circa 1900

The Victorians were concerned that welfare being handed out by parishes was too generous and promoting idleness - particularly among single mothers.

"The effect has been to promote bastardy; to make want of chastity on the woman's part the shortest road to obtaining either a husband or a competent maintenance; and to encourage extortion and perjury," said the 1832 Royal Commission into the operation of the poor laws.

The 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act that followed aimed to put a stop to all that. Conditions in workhouses were deliberately made as harsh as possible, with inmates put to work breaking stones and fed a diet of gruel, to make the alternative, labouring for starvation wages in factories or fields, seem attractive.

The shame of dying in the workhouse haunted the Victorian poor. Shame also stalked the drawing rooms of polite society, whenever a writer like Dickens or Henry Mayhew exposed the living conditions of the "great unwashed", half-starved and crammed into stinking, unsanitary slums.

But the driving force of the Victorian age was "self help" and the job of aiding the poor was left to voluntary groups such as the Salvation Army and "friendly societies", who focused their efforts on the "deserving poor", rather than those deemed to have brought themselves low through drink or moral turpitude.

It would take a war to make the alleviation of poverty for the masses the business of the national government.

The appalling physical condition of the young men who were enlisted to fight in the 1899 war between the British Empire and Dutch settlers in South Africa (the Boers), which saw nine out 10 rejected as unfit, shocked the political classes and helped make a war that was meant to be over quickly drag on for three years.

'War socialism'

Lloyd George and Churchill laid the foundations of the welfare state

David Lloyd George won a landslide election victory for the Liberal Party in 1906 with a promise of welfare reform. A means-tested old age pension was established for those aged 70 or more (the average life expectancy for men at that time was 48).

A national health system was set up, to be run by voluntary bodies, and, in 1911, the president of the board of trade, Winston Churchill, introduced a limited form of unemployment insurance and the first "labour exchanges," forerunners of today's job centres. It would not take long for the failings of the new system to be exposed.

The disaster of mass unemployment in the 1930s and botched attempts to provide assistance through the dreaded "means test" left a deep scar on the consciousness of the working class that would pave the way for the birth of the welfare state as we know it, at the end of the Second World War.

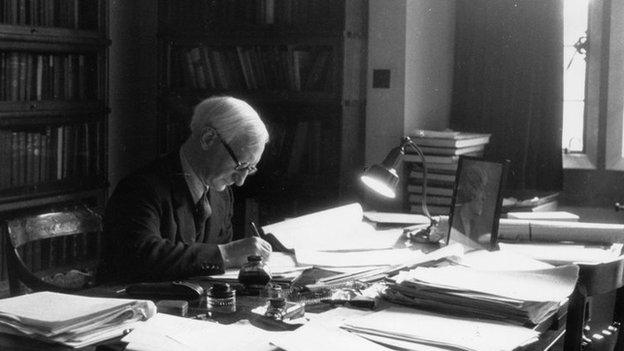

Liberal politician Sir William Beveridge - the father of the modern welfare state - wrote in his best-selling report, published at the height of the war, about the need to slay the five giants: "Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness".

Sir William Beveridge wanted to slay "five giants" that loomed over the population

The public's imagination was captured by the idea of "winning the peace" and not going back to the dark days of the 1930s after all the sacrifices of wartime.

Labour was swept to power in a promise to implement the Beveridge report, a task made easier by "war socialism" - a country united to fight for a common good and a massive state bureaucracy in place to run it.

'Benefit dependent'

A national system of benefits was introduced to provide "social security" so that the population would be protected from the "cradle to the grave". The new system was partly built on the national insurance scheme set up by Churchill and Lloyd George in 1911. People in work still had to make contributions each week, as did employers, but the benefits provided were now much greater.

When mass unemployment returned at the start of the 1980s, the system ensured nobody starved, as they had in the 1930s.

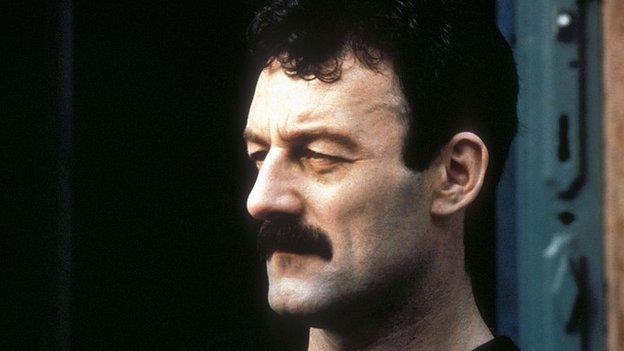

Boys from the Blackstuff depicted the death of working class pride in recession-era Liverpool

But the shame experienced by working class men, in particular, who had lost their job and were not able to provide for their families, captured in era-defining TV drama Boys from the Blackstuff, was an uncomfortable echo of the Great Depression.

As a new century approached and mass unemployment became a fact of life, old scare stories about a class of "idle paupers" taking advantage of an over-generous welfare system returned.

Anxiety about a permanent "underclass" of "benefit dependent" people who had never had a job - coupled with a sense that the country could not go on devoting an ever greater share of its national income to welfare payments - began to obsess politicians on the left and right.

The new Beveridge?

The defining TV drama, in an era where a life on benefits had lost much of its stigma, was Shameless, as the "benefits scrounger" became both an anti-establishment folk hero and a tabloid bogey figure.

Labour made efforts to reform the system to "make work pay" but it was the coalition government, and work and pensions secretary Iain Duncan Smith, that confronted the issue head-on.

Shameless made an anti-hero of 'benefit scrounger' Frank Gallagher

To his critics, Duncan Smith is the spiritual heir of the Victorian moralists who separated the poor into "deserving" and "undeserving" types - and set out to demonise and punish those thought to have brought it all on themselves.

But to his supporters, Duncan Smith is the new Beveridge. The great social reformer surely never envisaged a welfare system of such morale-sapping complexity, they argue, where it often does not pay to work.

"The state in organising security should not stifle incentive, opportunity, responsibility," wrote Beveridge in his report. "In establishing a national minimum, it should leave room and encouragement for voluntary action by each individual to provide more than that minimum for himself and family."

The Conservative government is committed to achieving full employment, seeing work as the answer to many of society's ills.

It has avoided the criticism levelled at the Thatcher government of the 1980s, that it allowed millions to rot away on benefits as a "price worth paying" for economic recovery.

But cuts to in-work benefits such as tax credits have handed ammunition to those on the left who accuse the government of trying to balance the nation's books on the backs of the working poor.

The debate opens up a new chapter in the story of Britain's welfare state, although many of the characters and themes have a very familiar ring to them.