Is this the end for the Freedom of Information Act?

- Published

- comments

So, is this the end for the Freedom of Information Act as we know it? Quite possibly.

The government has set up a commission of the great and the good, seemingly to make it easier for civil servants in central government to deny requests.

They will almost certainly propose a clampdown.

After all, the act is designed to hold the great and the good to account. They are not supposed to like it.

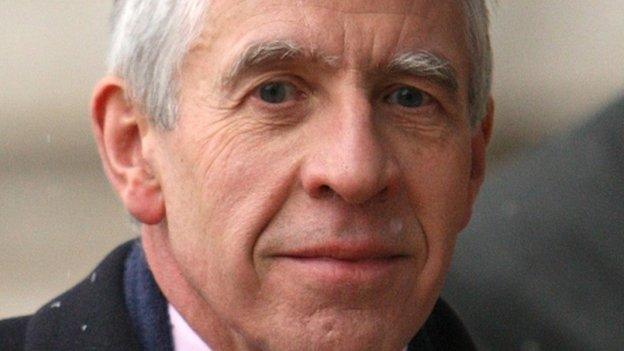

One of the panel, Jack Straw, is a noted sceptic who has already proposed restrictions to it.

By contrast, neither habitual requesters nor transparency advocates are on the panel.

The commission's remit, external is to look at two substantive issues that officials keep complaining about: "whether the operation of the Act adequately recognises the need for a 'safe space' for policy development and implementation and frank advice", and whether complying with the act is too much of a burden.

As it happens, we have answers to both questions, which were asked recently by a cross-party committee of MPs, external.

They looked at it with an open mind and they argued that the current system is broadly fine.

On cost, they said the Freedom of Information Act is justified as "a significant enhancement of our democracy" - and noted it had led to lots of savings.

The safe space?

So what about the "safe space" arguments? Under current law, section 35 of the Act, external allows the withholding of policy development work, private office communications and letters between ministers.

If that isn't enough, section 36, external allows ministers to withhold other information that would undermine the safe space for discussion.

Jack Straw has proposed restrictions

So why are officials looking to tighten these up? Because there is a public interest test attached to these provisions.

If a judge rules that, on balance, it is in the public interest for data to be released, even if they are covered by sections 35 or 36, then they are.

We know Mr Straw would like to unpick this.

He has already argued for "a class exemption, full stop" for anything that falls into these categories.

Anything that is deemed to be advice would be automatically exempt if ministers or civil servants decide that they would like it to remain secret, regardless of what a judge thinks.

It is worth considering what that would mean. They are not talking about the defence of legitimate state secrets nor the safeguarding of public safety.

It is cracking down on the release of information that an independent judge thinks it is in the public interest that you should be able to see, but which the most powerful people within government would like to keep secret.

That is, more or less, the information that a good transparency law should publish.

It is supposed to help us find cover-ups, incompetence and crookedness by the powerful.

A reform that got rid of this feature would undermine a critical purpose of the law - preventing the Hillsborough cover-ups of the future.

Judicial oversight is a safety valve in the system which balances the principle that there are legitimate things to keep secret with your right to know.

The problem with judges

So why do officials and ministers want rid of it? Fundamentally, there have been no individual releases that have actually caused any problems. That is the oddity of this complaint.

The root of this effort is that civil servants, since the Act took force in 2005, seem to have been astounded that judges see officials arguing against disclosure for what they are: a vested interest that will lie, exaggerate or overstate to hide embarrassing information about its employees and ministers.

Lord O'Donnell argued against releasing NHS risk register

Back in 2012, Lord O'Donnell, former cabinet secretary, was a civil service witness arguing that releasing the "risk register" for the coalition NHS reforms - a list of potential problems - would be dangerous.

This decision would engender a "chilling effect", he said.

If officials now came to fear such sensitive information was going to get released, they may be less candid in their assessments and keep worse notes.

The judge, professor John Angel, noted his view, external. Then he noted that Lord O'Donnell presented no evidence: it was just the special pleading of a high priest of the mandarinate.

Then the judge noted academic research which pointed out a lack of evidence for any substantial "chilling effect". He ruled against the civil service.

This appalled officials, but a well-functioning transparency law often should. It is - unusually - a piece of public policy that, rather unusually, is not devised for Whitehall's benefit.

The chilling effect

It is worth considering the argument raised by Lord O'Donnell, because it is what this clamp-down will focus on.

But the chilling effect remains a slightly baffling argument for the civil service to make publicly.

This problem could be very easily solved. Send a short memo to all officials notifying them that they will be fired if they fail to record their advice accurately and how they spend your money.

That is, after all, what we do to head teachers who fail to abide by the accountability conditions under which we fund schools.

But that will never happen.

The real reason why officials avoid leaving document trails is because they are encouraged to do so by the example of senior officials and by the public attitude of people like Lord O'Donnell.

Lots of Whitehall departments have bought in instant messenger systems which leave no trace.

The "chilling effect" is not a problem. It's policy.

Fundamentally, we ask people right across the public sector to conform to transparency laws - as well as league tables, scorecards and spending data releases.

The civil service is the only part of government which seems to have convinced ministers that they need exemptions from even the most basic accountability.