Labour leadership: Beware the muddled middle

- Published

Jeremy Corbyn is mobilising the left of the Labour Party

I've been off on a course for a week or so and feel rather detached from the news of the day.

Still, I can't help noting that the Labour leadership has been having an attack of the vapours.

Commentators, both well-meaning and mischievous, have been playing the role of maiden aunt to our fainting heroine, alternatively rushing around shrieking about the shame they are bringing on the family, and waving under their nose, Blairo (patent expired) "the stronger acting smelling salts" to bring them to their senses.

What has caused this alarm could be summed up in a crossword clue: "Exclamation of surprise, party ends in trash" (Cor! Bin).

The possibility that the next Labour leader will be the old stalwart of the Islington left, Jeremy Corbyn.

My course was in "hostile environments" and one of the things you learn is the danger of minefields - stick to the well-trodden middle path, don't go into the areas either side marked with red flags, for there death lurks.

Tony Blair's influence is still powerful in some Labour circles

This is Labour's sin in the eyes of the commentariat: that they are being lured, by the vision of a man with a beard, into the explosive land of red flags.

"You can only win on the centre ground!" is the complacent chorus.

No-one can doubt elections are won in the centre. Just ask Alexis Tsipras. Or Marine Le Pen.

The commentators are not exactly wrong. It's just they are right for all the wrong reasons, misunderstanding, unwittingly or for ideological purpose, the meaning of the centre.

Valuable perspective

But before we eviscerate the middle ground let us lie the swooning Labour party down on the sofa, usher out the maiden aunts, and urge everyone to take a pace back.

Complacency is never wise, but perhaps a bit of perspective is valuable.

We may be at a critical break point, but we may not. Democratic politics tends to go in cycles.

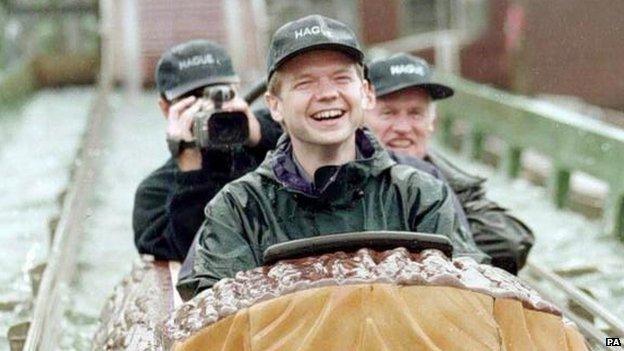

William Hague in infamous baseball cap

After a longish time in government, which ends in defeat and disappointment, it takes a while for the electorate to trust that party again.

It always feels terminal at the time. After Obama's victory in 2008 there were magazine headlines "the death of the Republican Party", external, without even a cautious question mark.

Two years after that they won the House, then in 2014 the Senate. Along the way they have collected a clutch of governorships.

They are not in the White House, they have serious problems, external, but dead, they ain't.

Or ask William Hague about baseball caps, external, saving the pound and what it was like to be Conservative leader of the opposition in 1997.

Labour are perhaps simply having their William Hague moment.

The grim news for them is that they still have to endure their equivalent of IDS and Michael Howard before finding a Cameron analogue.

The Conservatives' slow crawl back to electability was straight from the Tony Blair playbook, so it is hardly surprising that people have drawn the lesson that wooing your own hardliners fails, and moving to the middle works.

But times change.

Traumatic times

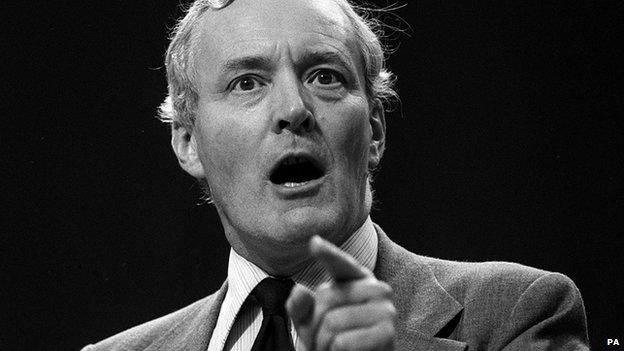

I am not playing down the fact that a Corbyn victory would be a moment of extreme trauma for Labour, would leave them branded unelectable by friend and foe alike and would raise ghosts from those who lived through the Bennite civil war and the formation of the breakaway SDP.

But that inevitability says something about the narrowness of debate, and the dangerous lure of the centre ground.

Tony Benn ran for the deputy leadership of the Labour Party in 1981

Corbyn , externalafter all, appears to be calling for a higher tax rate for the better-off, not the nationalisation, external of the commanding heights of the economy.

It is hardly surprising that Westminster journalists crave the ideologically soft centre, external.

None is on the minimum wage, let alone tax credits, nor are any, to my knowledge, owners of third homes on the Cayman Islands, or running big corporations.

They are nearly all university educated and live in London or the South East of England (Yes, all that goes for me, too).

There is group-think in the muddled middle, a fear of thinking outside a comfortable box.

They, like the politicians they write about, may dwell too much on the mechanics of winning, maintaining and exercising power, rather than why they want it in the first place.

This rather mechanistic approach excludes the real reason why most people get involved in politics - it also explains, why, increasingly these days, they don't bother.

It underscores why Jeremy Corbyn appeals to many Labour members, external.

He, like they, wants to change things.

You may label these ideas old-fashioned, or unworkable, but they are passionately held.

Appeal of principle

To them principle is important.

Fruitlessly opposing what they see as attacks on the poorest seems more noble than cunningly shadowing the Conservatives, in the apparent hope that no-one will spot the difference between the two parties.

Not long before I left the US, I was talking at a Tea Party convention to a couple of activists about who they wanted as the next Republican candidate.

One said, echoing the Buckley rule, external: "I want the most conservative guy who's electable."

Is Alexis Tsipras a centrist politician?

"That's where I'm different," chimed in his friend. "I want the most conservative. Period."

There will be Labour Party members who echo the sentiment, if not the political direction.

To them it looks as if becoming a leading Labour politician has become about how many of your core beliefs you are willing to jettison to get into power.

The Buckley rule:

Coined by William Buckley, the Conservative author and political commentator, during the 1964 Republican primary election which featured Barry Goldwater, the candidate of the right, and Nelson Rockefeller, regarded as from the liberal wing of the party.

He said he would support the "rightwardmost viable candidate".

This suspicion, from activists, creates uncomfortable echoes in the wider electorate.

There is a sizeable proportion of voters who don't like any of the main parties very much, and don't trust politicians.

What they don't like is the idea that politicians are in it for themselves, don't tell the truth, and will say anything to get elected.

A Labour leader who gives the impression that they are getting rid of most of the distinctively Labour bits of their policy, perhaps with the intention of smuggling them back in again at a later date, starts out doing the splits over the authenticity gap.

Social Democrats once had the luxury of rather impatiently accusing old-style socialists of clinging to the wreckage of the past.

Now social democrats themselves are holding tight to levers that are no longer attached to anything, external.

Complex picture

All but the most rarefied politicians must have noticed that real, walking, breathing voting human beings have a luxury they don't - to believe several contradictory things at the same time.

The world outside Westminster is a confusing place.

Is it really true that many people who voted Liberal Democrat in 2010 voted UKIP this year? Well, yes it is.

Constructing centre-ground politics to attract these wayward souls is more complex than pick-and-mix.

David Cameron: A competent centrist?

It is axiomatic that elections are won on the centre ground - it is obvious that to win you have to shift people from one party to another.

If you like, that is the centre ground. But it is where metaphor can be misleading.

The Venn diagram does not only consist of circles marked left and right.

People may be divided almost equally between preferring Marmite or marmalade on their morning toast, but it isn't a winning formula to mix the two spreads.

I'd suggest the centre is something more profound - shared desires that go way beyond ideology.

The centre ground of Tsipras (who ironically does now govern from the centre, but that's another story, external) was hope and a rejection of despair.

For Le Pen, it is perhaps a fear of change and a frustration with a grim economic future.

Cameron won the centre ground of competence - Ed Miliband was seen as extreme, but not because of the mansion tax.

He was seen as extremely unlikely to be a good prime minister.

Elections are won in the centre ground - but that means shared perceptions of competence and charisma, hopes and fears, not a nauseating mixture of Marmite and marmalade.