Where is Labour's 'Jeremy Corbyn mania' coming from?

- Published

Despair at Labour's general election defeat has given way to a mood of celebration on the British left, as their candidate emerges as the unlikely frontrunner in the party's leadership contest. But where is the support for Jeremy Corbyn, a previously obscure backbencher, coming from?

"All over the country we are getting these huge gatherings of people. The young, the old, black and white and many people that haven't been involved in politics before."

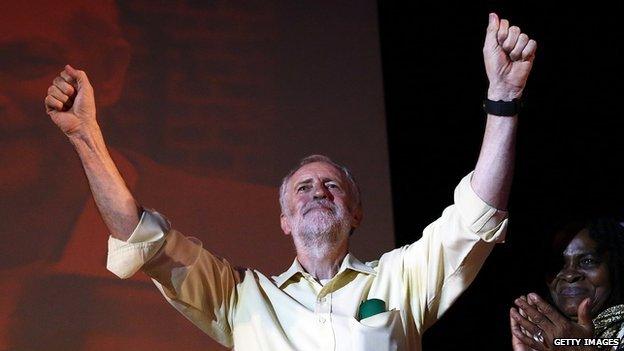

Jeremy Corbyn addresses a standing room only crowd in Euston, North London.

On this Monday evening so many people have turned up, some supporters are left standing in the street scouting for spare tickets.

It feels more like the build-up to an album launch than a political meeting.

For those unable to pack into the hall Corbyn ends up speaking from the roof of a waiting fire engine.

'Life on hold'

When he eventually makes it indoors he's mobbed by photographers, rapturous applause and the sounds of John Legend's contemporary protest song, Glory, thundering over the PA.

This is slicker, more vibrant and just plain bigger than anything left-leaning party politics has seen in Britain for a generation. Even Corbyn looks a bit surprised. As if this campaign has gone further than anyone could have predicted.

So what exactly is going on?

Corbyn is attracting a young audience for his message

Are Corbyn's supporters simply a collective of the usual leftist campaigners congregating under a contemporary banner or is there more to this left revival?

Lyndsey is a 30-year-old musician who believes her experience and support for Corbyn is representative of a shift in the landscape of British politics.

"I have put my life on hold, my music and my job to put time into this because it's something I believe in," she says.

"I really care about this so much because I think it's an opportunity to really change things."

More democratic

Lyndsey is in no way connected to the official Corbyn campaign but has made a series of online clips to address issues such as the housing crisis.

"It's about provoking discussion. I paid my £3 online and I'm trying to get as many people as possible to do the same."

Fans appropriate one of Ed Miliband's election catchphrases

Lyndsey had previously voted Green but just two weeks ago she became a "registered supporter" of the Labour Party. This "supporter" status gives Lyndsey a vote in the leadership election.

This new voting system was introduced to coincide with the current leadership election in an effort to encourage a more open and democratic contest.

Some longstanding Labour Party members have warned the move has unwittingly encouraged "entryism", the notion that members of far-left parties are joining Labour to mount a kind of coup. The party leadership fought a long, and ultimately successful, battle against Trotskyite entryists in the 1980s.

But the numbers don't add up.

The far left, although organised, just don't have the membership needed.

The Labour Party has grown rapidly in size since May's general election, with the total number of people signing up to vote in the leadership contest reaching 610,753.

The number of full party members has gone up from just over 200,000 in May to 299,755, with a further 121,295 people paying £3 to become registered supporters and 189,703 joining up through their trade union.

Lyndsey believes Jeremy Corbyn offers change

"Supporter" status provides the same voting rights as fully paid-up Labour members.

Even if there is evidence of small-scale entryism, this in itself could not determine a victory for Corbyn.

Listen to Mobeen's piece The Corbyn Effect, produced by Anna Meisel, at 20:00 on Thursday on BBC Radio 4's The Report.

A recent YouGov poll suggests Corbyn has extended his lead in the leadership race.

Much of the Labour establishment has been caught completely off-guard by the strength of Corbyn's support.

Former Foreign Secretary Margaret Beckett branded herself a "moron" for nominating Corbyn to stand.

"We were being urged as MPs to have a field of candidates. At no point did I intend to vote for Jeremy myself, nor advise anyone else to do it."

'Centre ground'

In 2010, backbencher Dianne Abbott stood in the leadership contest as a clear left candidate.

She failed to make any significant impact and many Labour MPs believed Corbyn would play a similar "symbolic" role in the current contest. So how exactly can the surge in Corbyn support be explained?

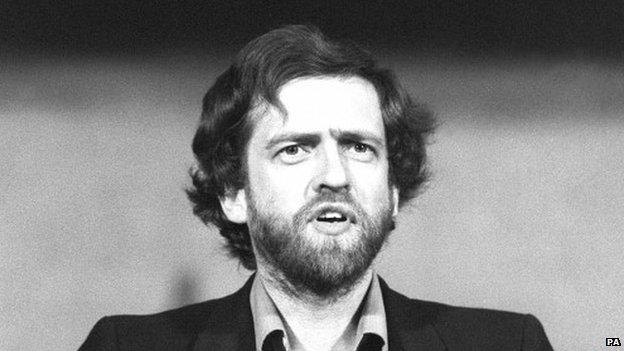

Corbyn was elected to Parliament in 1983

There is evidence to suggest the political landscape in Britain is shifting and Corbyn's recent success could be accredited to his core message connecting with an electorate to whom the "centre ground" no longer appeals.

Prof Paul Whitely, from the University of Essex, has been researching the demographic makeup of party membership since 1992 and most recently he has investigated norms in political opinion.

"We've been conducting surveys since 2013. The assumption in Westminster is parties need to be close together in the 'centre ground', but that is not what drives elections.

"Voters are not asking themselves, 'Where is Jeremy Corbyn on the left-right dimension?' They're asking themselves: 'Is this guy saying something which is new which might help me and deal with the problems that Britain faces?'

"The thing about Jeremy Corbyn, whether you agree or disagree with him, is that he has a new narrative and I think that's what's exciting people."

'Not tribal'

For voters like Lyndsey this is exactly what the Corbyn campaign has done.

"I have never wanted to vote Labour before and I will not stick with the party if Corbyn is not the leader. I am not tribal. What we have is a chance to really change things and I want to be part of that change."

The support for Corbyn could signal a shift not only for the Labour Party but for the way in which party politics works in Britain.

Prof Whitely explains: "The world has changed, there's no question about it. We have to learn from countries in continental Europe who have multi-party systems.

"The success of UKIP and the SNP show there is discontentment with the status quo and an appetite for new ideas. A lot of people inside the Westminster bubble are yet to catch up with this."

- Published12 August 2015

- Published11 August 2015

- Published12 September 2015