Jeremy Corbyn elected Labour leader: How did he win?

- Published

Jeremy Corbyn has been elected leader of the Labour Party. How did he do it? Here are some of the factors behind his against-the-odds victory.

1. The resurgence of the left

Tony Blair warned against a Corbyn victory but did his intervention backfire?

The Labour Party undoubtedly moved to the left under Ed Miliband's leadership, perhaps to a greater extent than the Westminster media and political establishment realised at the time.

Labour's new intake of MPs in 2015 is regarded as the most left-leaning in 20 years while the party's position on a range of issues - from welfare to Europe - is unrecognisable from its New Labour heyday, a fact acknowledged by Tony Blair. An estimated 70% of those who voted in the contest have joined Labour since 2010.

But it was a surge in popularity of grassroots campaigns outside the Labour Party that may have proved more decisive in the rise of Jeremy Corbyn.

The People's Assembly Against Austerity, which was launched in 2013, backed by trade unions, CND, the Communist Party and Mr Corbyn himself, drew large crowds at meetings and marches across the UK.

High profile speakers such as comedian Russell Brand and columnist Owen Jones caught the imagination of young, social-media savvy activists hungry for social change. Mr Corbyn also benefitted from the formidable organisational skills of his trade union backers - something the other candidates could not, or in the case of Andy Burnham who distanced himself from the unions - would not emulate.

2. Anyone could vote for £3

The rise of the anti-austerity movement would have had a minimal impact on the Labour leadership contest but for one crucial factor.

The change in Labour's leadership contest rules in 2014 was heralded as a way of reducing the influence of the trade unions but it also allowed anyone to take part in ballots for a £3 fee.

It received little attention at the time but nearly 200,000 people have taken advantage of it. This appears to have caught Jeremy Corbyn's leadership rivals, who focused their message on the existing Labour membership, by surprise. Only Mr Corbyn had a link to the £3 affiliate scheme on his campaign website.

Panic spread through the party when mischievous Conservative supporters started claiming they had signed up for a vote to sabotage the contest.

A different kind of panic took hold when it emerged that supporters of other parties, most notably the Greens but also far left groups, were attempting to sign up. There was much talk of "entryism" and a purge by party officials, which saw more than 3,000 people banned from casting a ballot because they were deemed not to support Labour's "aims and values".

Only Mr Corbyn, of the three candidates fully embraced the new arrivals (apart from the Conservatives of course), promising them a role in setting Labour's policy agenda.

3. Those 'moron' MPs

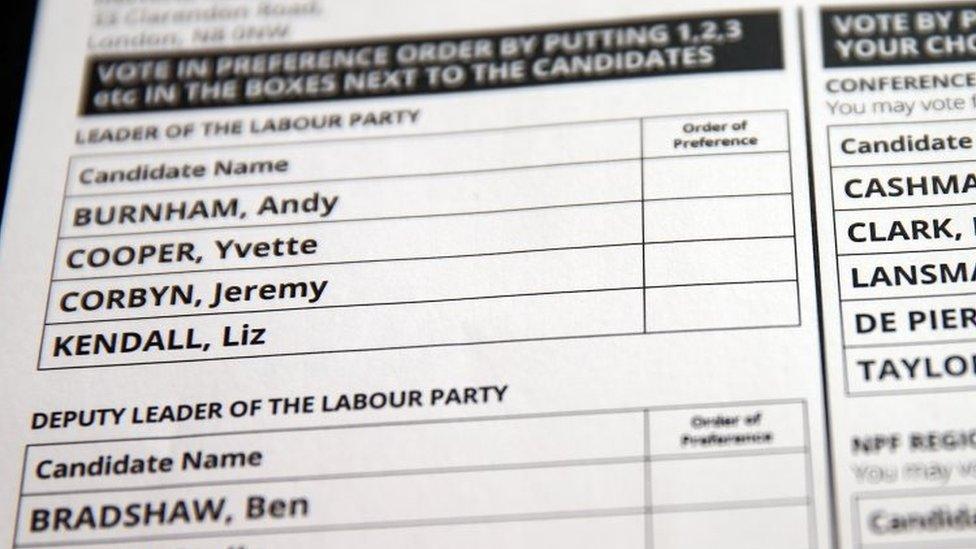

Jeremy Corbyn got 36 nominations - some from Labour MPs who did not support him

Jeremy Corbyn surprised many people when he entered the race weeks after his rivals, in a low-key announcement to the Islington Tribune.

At the time it was generally assumed he could not possibly win, with commentators describing him variously as a "maverick", external, "Caracas Corbyn, external" and a member of the "loony left", external, suggesting that he was trying to make a point rather than get elected, external.

He would not even have been a candidate in the first place if it hadn't been for the generosity of some of his fellow MPs.

Under the contest's rules, he needed the support of 35 MPs - 20% of the parliamentary party - to be nominated and to get onto the ballot paper. This looked unlikely as he hovered around the 30 mark close to the deadline in mid-June.

Yet, he managed to get over the threshold with minutes to spare. The reason he did so was that a number of MPs - including some with diametrically opposed views - "lent" him their votes. At the time, they argued Labour needed the widest possible debate after its election defeat and it would be wrong if the left of the party was excluded.

Those MPs who helped Mr Corbyn over the line were memorably derided by John McTernan, ex-adviser to Tony Blair, as "morons who need to have their heads felt". One of them, former acting party leader Margaret Beckett, ruefully owned up to being a "moron".

4. Missing opponents

Potential opponents fell by the wayside until only three others were left standing

Jeremy Corbyn's task was undoubtedly made easier by the absence of heavy-hitting rivals.

The pool of potential opponents had already been reduced by Labour's election losses while senior figures within the party - including deputy leader Harriet Harman and former home secretary Alan Johnson - quickly ruled themselves out of the contest.

The party's "next generation" - those elected in 2010 and since - also largely decided to sit out the fight with Chuka Umunna's decision to quit the race after only a couple of days symptomatic of their tentativeness. Dan Jarvis, a former soldier who was much touted as a future leader, also declined to take part.

With two of Mr Corbyn's opponents - Andy Burnham and Yvette Cooper - having served in the Cabinet under Gordon Brown and also having been close allies of Ed Miliband and the third, Liz Kendall, tagged as the "Blairite" candidate, Mr Corbyn was able to associate his rivals with the erosion of Labour support during the past decade and argue effectively that only he offered a true break from the recent past.

5. Popular enthusiasm

Corbynmania was born as the previously unheralded MP addressed thousand-strong crowds

There may have been a record number of campaign hustings but few of them captured the public imagination.

In contrast, Jeremy Corbyn's public appearances drew crowds that few politicians can dare to dream of. Thousands flocked to events up and down the country to hear him speak. First, it was standing room only, then people found themselves being turned away - with the candidate at one point addressing hundreds of people in a London street while standing on top of a fire engine.

This was more than an inkling of how Corbynmania had energised the previously lacklustre campaign.

Although 20 years older than his rivals, his ability to appeal to idealistic young people, excited by his anti-austerity message and rejection of decades-long orthodoxies, also took the Westminster establishment by surprise and marked him out from his opponents.

6. Campaign style

Jeremy Corbyn's attire will be different to his predecessors

In an era of sharp suits and sharper haircuts, Jeremy Corbyn immediately stood out from the crowd.

His slightly ruffled trademark vest and shirt combination - he was rarely seen wearing a jacket or tie during the campaign - may have been mocked by Private Eye but it gave him an authenticity and distinctiveness rare in modern politics.

Jeremy Corbyn, whose small but select group of advisers is led by former Ken Livingstone aide Simon Fletcher, also remained unruffled on the campaign trail, eschewing soundbites and refraining from personal attacks while his opponents' briefed against each other.

He avoided stunts and - apart from a few testy exchanges, most memorably on Channel 4 News and BBC Radio 4's The World at One - he handled the unaccustomed media scrutiny well. There will be plenty more to come no doubt.