No appetite for Lords reform?

- Published

The combination of Lord Sewell's unorthodox choice of underwear, and the latest nominations to the peerage may have re-energised calls to abolish or democratise the House of Lords...but don't hold your breath.

There is a very simple reason why big ticket reform of the Upper House - elections, or even outright abolition - is not going to happen; it would require a good two years of a Parliament.

MPs and peers would spend a vast chunk of their time on an issue most people simply don't care about. Not the economy, not immigration, not Europe or the NHS. Instead, they would be consumed by passionate debates on constitutional arcana and legislative process.

And there simply is not the head of steam needed to make a government do that.

When Herbert Henry Asquith's Liberal government clipped their lordships' wings with the 1911 Parliament Act, it was because the Lords had blocked their social programmes and even Lloyd George's People's Budget.

They had been elected (several times), but were not being permitted to govern. Lord Sewell's antics don't add up to a comparable crisis.

Nor does the latest set of nominations. The current hue and cry is already fading and will soon be overtaken by more urgent issues.

Creating problems?

More than that, the size and membership of their lordships' House is just one facet of the UK's constitutional problems and addressing that, without touching on a whole series of other issues, would probably create more problems than it solves.

The starting point is that the Lords is not some obsolete constitutional organ that could simply be cut out of the body politic like an inflamed appendix, without any real affect on the health of the whole organism. It does, in fact, do rather a lot. As the excellent Constitution Unit at UCL documents here, external, peers have regularly defied the government and forced ministers to at least compromise on all manner of issues.

They are far more adept at detailed scrutiny of legislation than MPs - not least because the Commons standing orders allow large chunks of bills to be forced through with no detailed debate.

Get rid of the Lords, and the Commons would have to up its game considerably, or the voters would find themselves saddled with a lot more bad law. The simple fact that a bill has to pass through two houses rather than one means that technical defects and bad policy have more chance of being detected and stopped.

The idea that Lord Sewell's activities make the case for an elected Lords is risible; elected politicians have hardly been free of financial or sexual scandal over the years. There's a perfectly legitimate argument for having elections to the Upper House - but that isn't it.

If not elections, then maybe a more transparent appointment process? When the former Liberal Leader David Steel tried to push through a series of Lords Reform Bills, he included the idea of a statutory appointments commission and the abolition of by-elections to maintain the 92 hereditary peers in the Upper House. Both proposals ran into heavy opposition and were dropped from later incarnations of his bill.

In the end, all that was left was powers to remove peers found guilty of serious misconduct.

Then there's the claim that the House is "growing exponentially".

Er, no.

It's grown substantially in recent years, to be sure, but the increasing expectation that peers do retire from active membership when they age, plus the activities of the grim reaper means that we have probably reached, or maybe even passed 'Peak Lords'. Unless the prime minister piles in with more appointments, the House may actually begin to shrink a little, although it does remain rather too large.

On that subject, I understand that Lord Steel has now put down a motion for debate (probably on Tuesday 15 September) which would require peers to retire at the general election at the end of the Parliament in which they reached their 80th birthday (but with a get-out clause if they really really wanted to stay).

Peers may pounce on that idea to show that they are taking notice of the disquiet over the last wave of appointments, but the reality is that it would only make a modest difference to present trends.

My point is that there is a reason why the fundamental Lords reform promised in 1911 by Asquith has yet to materialise. There is no agreement on what is to replace it. Nick Clegg's bill to introduce some elected peers was dished when Tory backbenchers threatened to rebel against it, because an elected Upper House might threaten the primacy of the Commons (or maybe because they just wanted to clobber the then DPM).

Over the years we've had incremental reform, notably the curtailment of the Lords right to defy the Commons in two Parliament Acts, but also the creation of life peers and the exclusion of most (but not all) hereditaries, and an independent appointment process for some independent peers. So the hereditary Lords of a century ago have mostly been replaced by nominated legislators - ex MPs and ministers, top establishment figures like senior civil servants, ex-judges and retired generals, plus a smattering of distinguished non-politicos from academia and the professions.

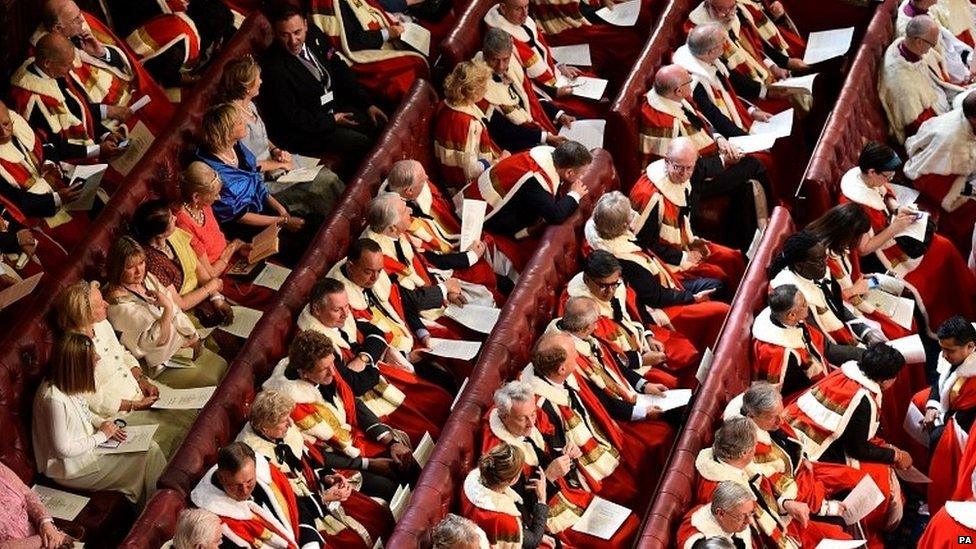

It might not be what a constitutional convention would arrive at, given a blank sheet of parchment, but beneath the faux-medieval Victorian pageantry, the modern House of Lords kinda works.

And as Nick Clegg discovered, it is very difficult to change. We may see further tweaks - perhaps more exclusion of peers who fail to participate, or some incentives for voluntary retirement.

But my bet is that any dramatic Lords reform will come as part of a package of devolutionary measures prompted by the need to address the future structure (and survival) of the UK.