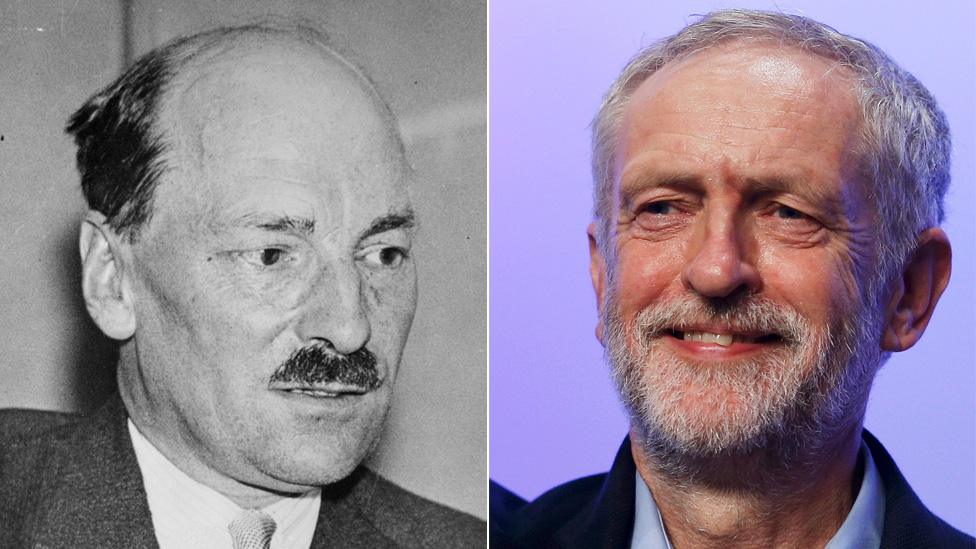

Is Jeremy Corbyn a latter-day Attlee?

- Published

Jeremy Corbyn prefers the collective approach to leadership also favoured by Clement Attlee

The idea that just one person should be entitled to determine the policy of his or her political party is a strange one, for no leader of a democratic party was ever chosen because he or she was believed to have a monopoly of wisdom.

Yet the assumption that the party leader should have the last word on everything has almost imperceptibly gained currency in British politics during recent decades.

It is a notion especially at odds with the traditions of the Labour Party, in which, historically, the shadow cabinet (when the party was in opposition), the parliamentary party (PLP), and the party in the country (through its elected representatives on the National Executive Committee) shared the task of policy-making.

The annual party conference (until the New Labour era) also had a policy-making role, although what happened in between party conferences was always more important.

The influence of each of these components in relation to the others varied over time, but the shadow cabinet, and especially its most senior members, generally wielded the greatest day-to-day power.

While the party leader had more influence than any other individual in the top leadership team, he could not dictate policy.

Collective cabinet responsibility

The most respected of all Labour leaders, Clement Attlee, who led the party for 20 years, was a prime minister (1945-51) who let individual ministers make their own decisions, subject to getting cabinet agreement for the most important issues of principle.

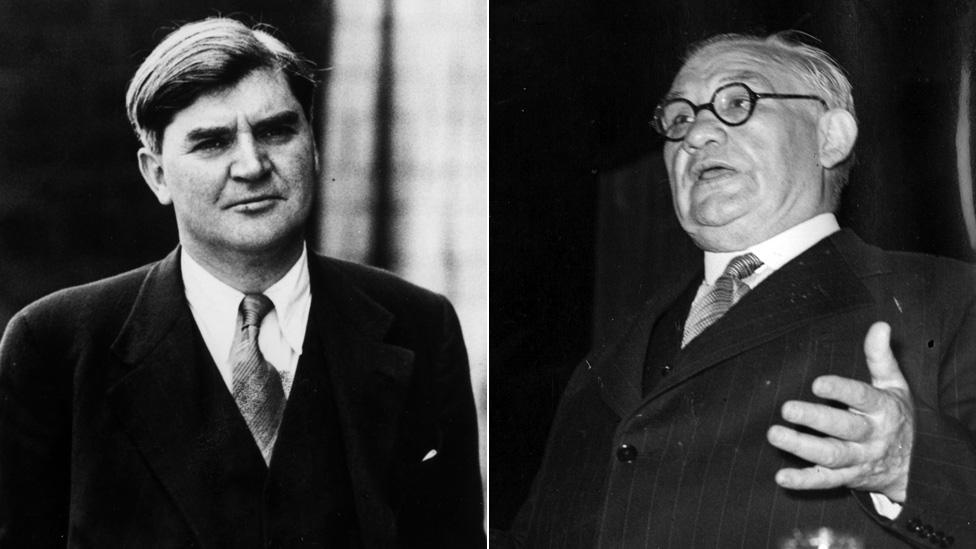

That government contained people of very diverse views - from Ernest Bevin and Herbert Morrison on the right wing of the party to Aneurin Bevan on the left (although their support for very high levels of income tax to fund public spending and for extensive public ownership would put even the Labour "moderates" of 1945-51 to the left of the policies espoused today by Mr Corbyn.)

Bevan and Bevin represented different strands of thought in the Labour movement

When commentators speak of Attlee "creating the National Health Service", they are projecting the contemporary cult of the leader on to a man who would not have dreamt of making any such claim.

The minister responsible for ushering in the NHS was Bevan, to whom Attlee gave full credit while stressing that the cabinet collectively "share the blame or the credit for every action of the government".

Accommodating himself also to policies pressed on him by backbench Labour MPs, Attlee acknowledged that "other people may perhaps be wiser than oneself".

Extensive use of the first-person singular was not a feature of Labour Party leaders' speeches prior to Tony Blair's election, but it was a practice continued by both of his immediate successors, Gordon Brown and Ed Miliband.

Mr Corbyn has, however, broken with that.

He has broken also with the idea that party policy emanates from the leader.

That was most notably espoused, external by Mr Blair, who wrote that even if people disagreed with the 2003 invasion of Iraq, they "sympathised with the fact that the leader had to take the decision".

Mr Corbyn has made no pretence to be "an all-seeing, all-knowing leader, external".

He must recognise that he cannot dictate policy but can try to persuade the shadow cabinet and the parliamentary party that some of his policy preferences have merit.

Tony Blair adopted a more presidential style of political leadership

In the short term, he can cite his intra-party electoral triumph as constituting a mandate for greater radicalism.

But there is a tension between his earlier rejection of top-down policy-making and his claim to Laura Kuenssberg on Wednesday that he will have the final say.

On the evidence so far, Mr Corbyn is closer in leadership style to Attlee than to Mr Blair.

Attlee, however, had several huge advantages over Mr Corbyn, especially by the time he became prime minister.

By then, he had already been for five years a linchpin of the wartime coalition government and, from 1942, the official deputy prime minister to Winston Churchill.

As Labour's landslide victory in 1945 indicated, the egalitarian and public-service oriented policies of the party were in tune with a large swath of the electorate.

Moreover, although the PLP included Labour rebels on the left and a smaller number on the right, as a whole it respected Attlee and was supportive of him.

Attlee saw himself, and was seen, as a party loyalist and as a centrist within the Labour Party.

He was able to head a government which, collectively, moved the centre of the political spectrum in Britain leftwards and, in many respects, set the political agenda for a generation.

Different times

Mr Corbyn has assumed the Labour leadership in a different climate of opinion.

In political experience and parliamentary support, his position is vastly inferior to Attlee's.

Clement Attlee:

succeeded George Lansbury as Labour leader in 1935, being confirmed in post only after the general election of that year, which Labour lost

entered the wartime Government of National Unity under Winston Churchill in 1940, officially becoming deputy prime minister in 1942

became prime minister in the Labour landslide of 1945, remaining in office with a hugely reduced majority in 1950, before losing the 1951 election to Churchill's Conservative Party

his administration is credited with founding the modern welfare state, including the National Health Service

Attlee's government also oversaw a large-scale nationalisation programme, bringing industries such as coal, electricity, gas, iron and steel under direct state control.

noted for his under-stated public persona, he was nevertheless able to lead a government of diverse and potentially combustible talents, including Aneurin Bevan, Ernest Bevin, Herbert Morrison, Stafford Cripps and Hugh Dalton

So far as the parliamentary party goes, he starts with less support than that enjoyed by any Labour leader subsequent to Attlee.

While Mr Corbyn's views on economic policy may be close to Attlee's, that now places him on the left of the party, not its centre.

A collegial and inclusive style of party leadership may come naturally to him, but he really has no other option.

He will also have to learn a great deal on the job to have any hope of leading the Labour Party into the next general election.

Archie Brown is the author of The Myth of the Strong Leader: Political Leadership in the Modern Age (Vintage paperback, 2015).

- Published14 September 2015

- Published16 September 2015