It could be a conference season for the ages

- Published

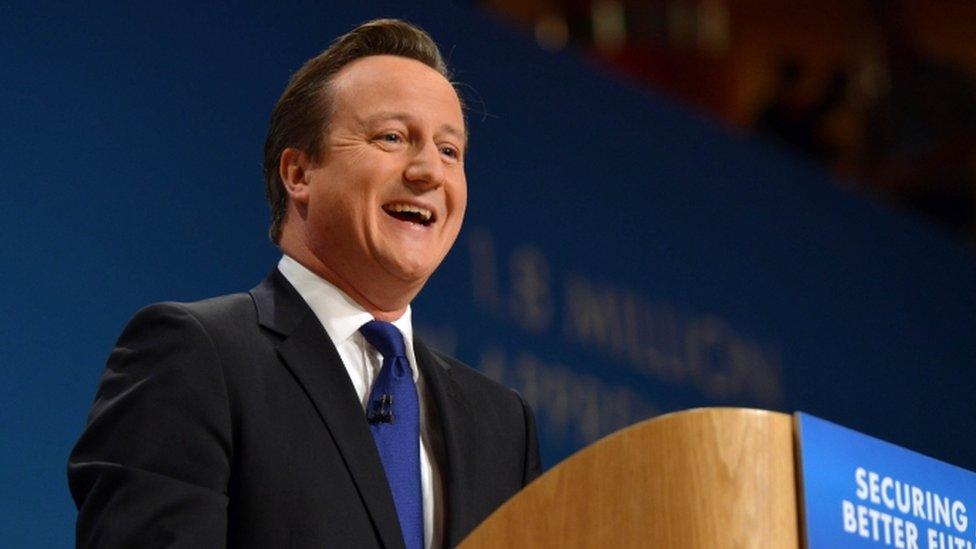

Can the prime minister afford to smile?

The Conservatives' surprise election victory sent shock waves through the body politic that will resonate for a long while.

Some of those convulsions are on display in the first conference season since their victory.

UKIP and the Lib Dems may be interesting, but it will be Labour's fraught week that will fascinate.

The Conservatives are masters of all they survey, and it was an act of kindness that the Daily Mail did not drop Lord Ashcroft's brawny bombshell on the day of David Cameron's speech.

The prime minister could argue he has had astonishing success with plans to encourage national happiness, external, at least if the reaction to an unsubstantiated porcine allegation on Twitter is anything to go by.

While national broadcasters behave with the care and responsibility of a nanny directing her charges' attention away from two dogs copulating in the street, everyone else is falling about laughing, giving Cassetteboy a triumph and zillions of hits.

But it barely matters.

I hesitate to write "water off a duck's back" under the circumstances, but even the US politician and master of the pithy phrase Edwin Edwards never had it so good, external.

The prime minister will endure a few more awkward moments, but Chancellor George Osborne can afford to giggle.

Although the conferences can be something of a showcase for politicians, they are mostly something to be endured and survived.

Bad moments

With a few notable exceptions, memorable moments tend not to be good ones for those involved.

Think about Ed Miliband's walk in the park, and forgetting to mention the deficit.

Ed Miliband endured mixed headlines at Labour conferences

This year, there will be a curious mixture of triumphalism and the deepest gloom.

One MP on the right of the party joked to me that as the people usually grouped outside the hall, selling left-wing newspapers and shouting about betrayal will be on the inside, in charge, he and other besuited MPs should be on the pavement protesting, chanting about the need for fiscal responsibility.

It was a burst of gallows humour from a man who seems deeply depressed, wondering whether he has wasted 30 years of his life on a party that he now thinks is unelectable.

For the team around Jeremy Corbyn the challenge is clear - whether they can stop the conference degenerating into bitter snipping and recriminations, and whether their man can capture the mood that propelled him into power, and excite a wider audience in the way that he appealed to those who voted for him.

Memorable conference moments:

George Osborne 2007: Gordon Brown was thought likely to call a general election, which Labour were favourites to win. Mr Osborne spiked his guns by announcing plans to raise the threshold on inheritance tax

David Cameron 2005: ignited his campaign for the Conservative leadership with a much-praised speech delivered without using notes or an autocue

Tony Blair 1994: announced plans to remove the totemic Clause IV of the Labour Party constitution, ending the party's commitment to nationalisation

Neil Kinnock 1985: launched a controversial attack on the Militant Tendency, provoking much booing and a walkout by Eric Heffer, a leading figure on the left of the party

David Steel 1981: told delegates at the Liberal Assembly "to go back to your constituencies and prepare for government"

Margaret Thatcher 1980: rejected calls to dilute her tough economic polices with her "The Lady is not for turning" speech

For the Labour right, people who have been in charge of their party for two decades or more, the challenge is almost overwhelming.

There is not, as far as I can tell, any coherent plot. It is far too early for that.

Some may still see David Miliband as the king across the water, but names of alternative leaders are almost irrelevant.

They know there is no point in re-running a contest just to get the same result.

They know that Mr Corbyn will have to have failed and seen to fail before they make a move. It makes the local, London and Scottish elections next year really rather important.

Policy concerns

But for the Labour right a likely outcome - modest gains, bumping along in the opinion polls, will increasingly raise the question of what they do and when they do it.

They worry about not just Mr Corbyn's policy, but what they see as a lack of coherence, a lack of grip.

David Miliband: king across the water?

Although they are delighted he hasn't stuck to a hard line on the EU or Nato, some are also dismayed at the casual way of making policy.

The trouble is while they insist that Mr Corbyn sticks to an open, tolerant view towards dissenters - even allowing members of the shadow cabinet to disagree with him on the airwaves - they also know that is a political disaster.

Come election time, it will be hard to persuade anyone to vote for a party that speaks with two voices.

Many insiders think, even aside from his policies, Mr Corbyn simply doesn't have the organisational ability, stamina and temperament to do the job.

They could be wrong, and even if they are right, it doesn't solve their ideological problem - there will be others waiting in the wings.

For those who regard themselves as moderates, there is no clear way to regain their party - after all it took a bit of an accident for Old Labour to do the same.

Headlines, of course, declare there is a Labour civil war.

That is understandable, but wrong.

Jeremy Corbyn's performance will come under intense scrutiny

At the moment, there are two armed camps, warily eyeing each other, both shocked by what has just happened.

Brawling could break out, but clear-headed assassins will bide their time.

While a bulk of Labour MPs look back on the centre ground with a certain nostalgia, Conservatives see a whole vista of opportunity open up.

Mr Osborne's summer Budget was designed to portray the Conservatives as the "real" party of working people after Labour's defeat, and every strategic bone in his body must scream out that he should do more, in word and deed, to occupy abandoned territory.

But as others have pointed out, external, Labour's internal problems will give the government the space to chuck plenty of red - or blue - meat to their supporters.

The Conservatives need to worry not about next year's election so much as the European referendum, probably later next year.

It will be a dangerous time, with plenty of furious dissent within the party.

Renegotiation will not be easy for Mr Cameron, selling it to his backbenchers even harder.

He could not survive losing the plebiscite - but the Conservative Party could and would.

To be a Tory, now, is to face unbounded opportunity.

For others, the landscape is bleak.