A not very British coup

- Published

The Sunday Times story appeared to show the taboo of the military getting involved in party politics being broken

The Sunday Times recently reported on a potential mutiny in the ranks of the British Army, should Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn ever become prime minister.

The newspaper quoted an unnamed serving general. He said "feelings are running very high" at the very thought of a man leading the nation who might scrap Trident, withdraw from Nato and make further cuts to the size of the armed forces.

The Army, he's alleged to have said, "just wouldn't stand for it".

Given the British Army currently has more than 100 generals, it is perfectly possible that one of them might have gone "rogue" and broken the taboo of getting involved in party politics.

In my experience most generals are bright enough to stay clear of the subject and are happier to let you guess their political views.

The trouble is that some former senior officers have not helped. They've nailed their political colours to the mast.

General Lord Dannatt, the former head of the army, openly flirted with the Conservatives, external and Admiral Lord West, a former First Sea Lord, served as a security minister in the last Labour government.

There is considerable anger among the current military top brass who believe it's undermined the important rule of not engaging in party politics.

Crossover and tensions

Yet the military are happy to turn a blind eye when more junior officers pursue a political career.

There are 51 MPs in the House of Commons who've served in the military, either as regulars or reservists. Perhaps reinforcing a perception, all bar two of them sit on the Conservative benches.

British officers have aired differences with the government over strategy towards Iraq and the so-called Islamic State

There is clearly a crossover between politics and the military and there are clearly tensions.

In America it's sometimes played out in public. In the run-up to the invasion of Iraq, General Eric Shinseki clashed with Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld over the number of US troops needed after the invasion of Iraq.

He resigned.

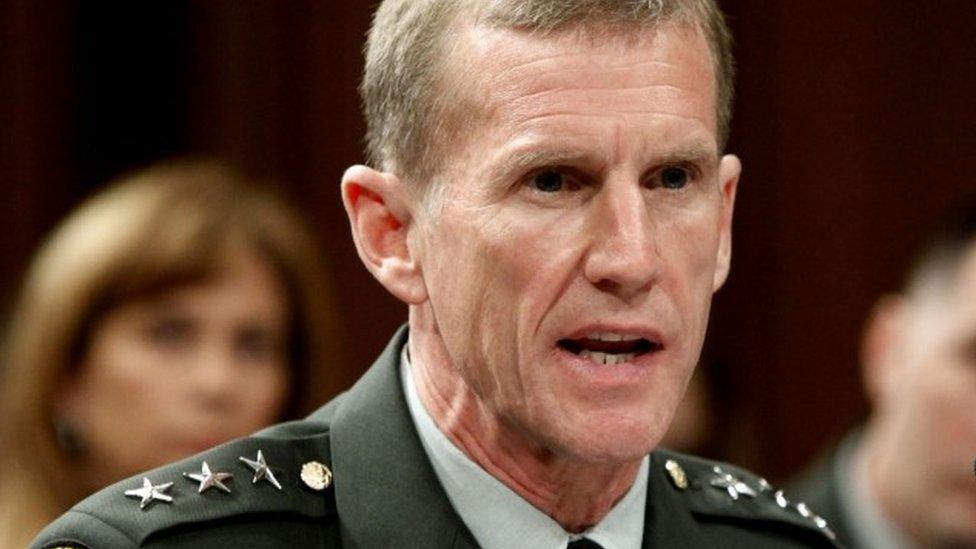

General Stanley McChrystal, external had similar disagreements with the Obama administration over the number of troops required in Afghanistan.

He too resigned after his staff spent an evening drinking with a Rolling Stone journalist and airing their views of the commander-in-chief.

Gen Stanley McChrystal resigned from his position in the US armed forces after his staff criticised President Obama

Senior British officers too have aired differences with ministers over strategy in Iraq, Afghanistan and, more recently, in fighting the so-called Islamic State group.

But they've rarely broken rank, at least until they can do so from the comfort of an armchair and a generous retirement pension.

British Army

The number of regular troops is shrinking, from 163,000 in 1978 to 102,000 in 2010 and 82,000 in 2020

The government has said it does not want whole regiments to be scrapped; some will be merged, others face "salami slicing"

The Army will become more reliant on part-time soldiers; the number of reservists will double from 15,000 to 30,000 by 2020

The government says Britain will have an effective, well-equipped fighting force, integrating regulars and reserves

Analysts say the Army will have resources for only one major operation at a time, and there will be swingeing cuts to support units such as logistics and engineers

Politicians, though, must take some of the blame for this sometimes fraught relationship.

They too have been keen to play armchair generals. Winston Churchill liked to interfere in the detail of military plans. He wasn't afraid to sack those generals whom he believed were underperforming either.

Better under Labour?

More recently, during the Libya campaign, David Cameron slapped down a senior RAF officer who dared suggest that his resources were stretched.

Mr Cameron's advice to Air Chief Marshal Simon Bryant was: "You do the fighting and I'll do the talking." Words that suggest there's not always a healthy respect for the professional views of the military.

But before assuming that most senior military officers are closet Conservatives, it's worth remembering the armed forces have often fared better under Labour in terms of resources.

Some in the military would share Mr Corbyn's views about Trident, albeit for different reasons

The last coalition government, with a Tory prime minister and Tory defence secretary, carried out some of the largest defence cuts in recent history.

True, many who wear the uniform and swear allegiance to the Queen would probably find it odd to serve a prime minister with republican views.

Most would fundamentally disagree with Mr Corbyn on the use of military force. But some in the Army and the RAF would share his views about Trident - albeit for very different reasons.

Not because they're unilateralist, like him. But because they question the cost of replacing it while conventional forces are being cut.

Defend the realm

The unnamed general quoted in the Sunday Times though appears to have missed the most important point - a failure to understand a parliamentary democracy or even current politics.

He should have noticed that many Labour MPs are at odds with Mr Corbyn's views on Trident, Nato membership and air strikes on Syria.

It's their job to make Labour electable. The Army's is to defend the realm, not to tell people how to vote.

Military coups might happen in Pakistan, external, Egypt, Fiji, external or Burkina Faso. But they're not very British.

- Published26 February 2015

- Published22 September 2015