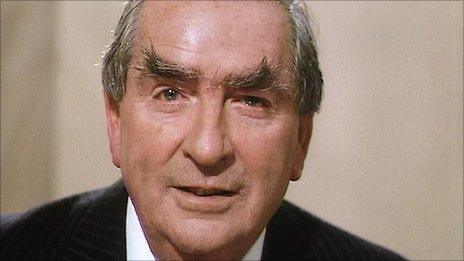

Denis Healey: A political bruiser with a sharp wit

- Published

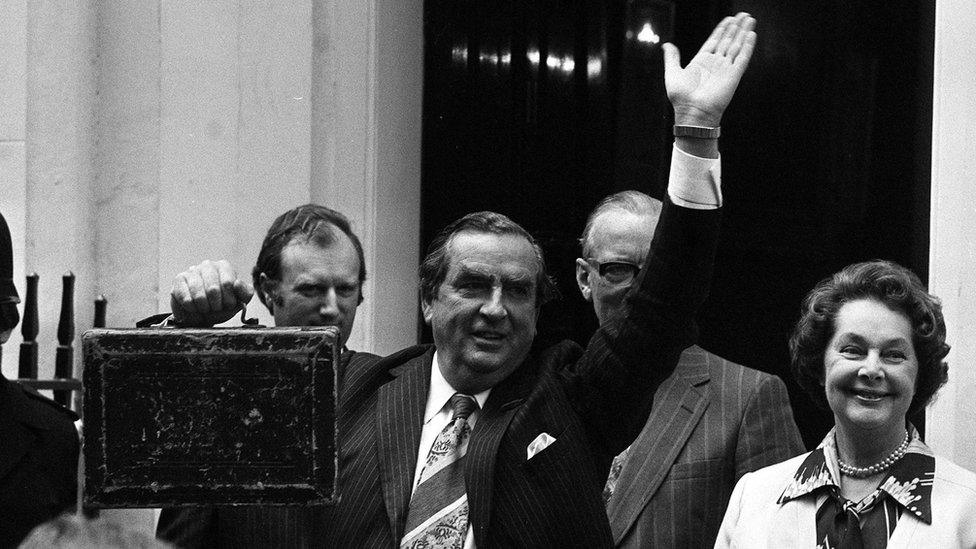

As chancellor, Healey had to introduce large spending cuts in a time of economic strife for the British economy

Denis Healey - who has died at the age of 98 - was the last of the great post-war generation of political "big beasts" who dominated British government in the 1960s and 70s.

The last surviving member of Harold Wilson's first Cabinet, formed after the Labour Party's narrow election victory in 1964, he was defence secretary for the six years until Labour lost office in 1970.

After gaining a first at Oxford before the war, where his contemporaries included Ted Heath, he joined the army and distinguished himself for his bravery as a beach master at Anzio.

He made a passionate speech to the 1945 Labour conference in his military uniform, but failed to win a seat in that election which swept the party to power.

He finally entered the Commons at a by-election in 1952 after Labour had lost office. It meant that by this year he had the earliest memories of the Commons of any surviving MPs as well as being the oldest peer in the Lords, at 98.

(Only last week I had written seeking a radio interview about his earliest parliamentary memories, to be told by his family that he was unwell and I should try again in a few weeks, as he still liked doing interviews.)

'Till the pips squeak'

After his election, it wasn't long before the young Healey was getting noticed. During the 1956 Suez crisis, when Britain invaded Egypt to try to regain control of the Suez Canal - nationalised by the Egyptian leader, Nasser - there was wild disorder in the Commons and what amounted to a rolling censure debate of the government, led by the conservative prime minister, Sir Anthony Eden.

Healey drew a wounding parallel between Britain's action in Egypt and the simultaneous Russian invasion of Hungary. He recalled: "I asked whether Eden had sent a message of congratulations to Khruschev for his success in Hungary… it went down well with my side but not so well with the Tories."

Healey (second from left) entered the Commons in 1952, and later served as defence secretary and chancellor

As defence secretary, he would later oversee the withdrawal of British forces East of Suez and when Wilson returned to government in 1974, he was appointed chancellor and delighted Labour activists by promising to squeeze property speculators "till the pips squeak" - words Labour's new left-wing shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, would surely be proud of.

But Healey had to face down the wrath of the Labour conference in 1976 and was virtually shouted down as he told his party some home truths about the scale of spending cuts they must accept to keep Britain solvent, after he had been forced to go "cap in hand" for an emergency loan to the International Monetary Fund as the economy teetered on the brink of collapse. He later described it as the most harrowing day of his life.

The spending cuts Healey imposed - as godfather of "austerity" economics - produced more savings in one year than George Osborne has planned for nearly a decade.

But Healey had one very unlikely admirer: Margaret Thatcher. The new Tory leader - whom he would ridicule as "The Great She Elephant" and "The Catherine The Great of Finchley" - suggested in her memoirs that Healey's 1976 Budget was a turning point and that the economy began to recover after he announced a money supply target for the first time. Monetarism - the economic creed adopted by Thatcher's Conservative Party - was said to be a Healey invention.

Volcanic clashes

Healey was an intellectual and didn't tolerate fools gladly, if at all, as Neil Kinnock has observed.

His frequent volcanic clashes with his equally strong-willed Liberal "shadow", John Pardoe, during the Lib-Lab Pact which kept Callaghan's minority government in power, have been recounted by Healey's number two in the Treasury at the time Joel, later Lord, Barnett. He and the then-Liberal Party leader, David Steel, had to intervene as peacemakers, he recalls.

This intolerance, coupled with anger over the cuts, and Healey's failure to cultivate a band of followers among Labour MPs, probably contributed to his failure to become party leader on two occasions. First, after the retirement of Harold Wilson in March 1976 and then of his successor, James Callaghan, after Labour lost the 1979 election following the Winter of Discontent. Several Labour MPs who later defected to the newly-formed SDP said they voted against Healey in order to land the Labour Party with Michael Foot - an unelectable left-wing leader - and so help their new party.

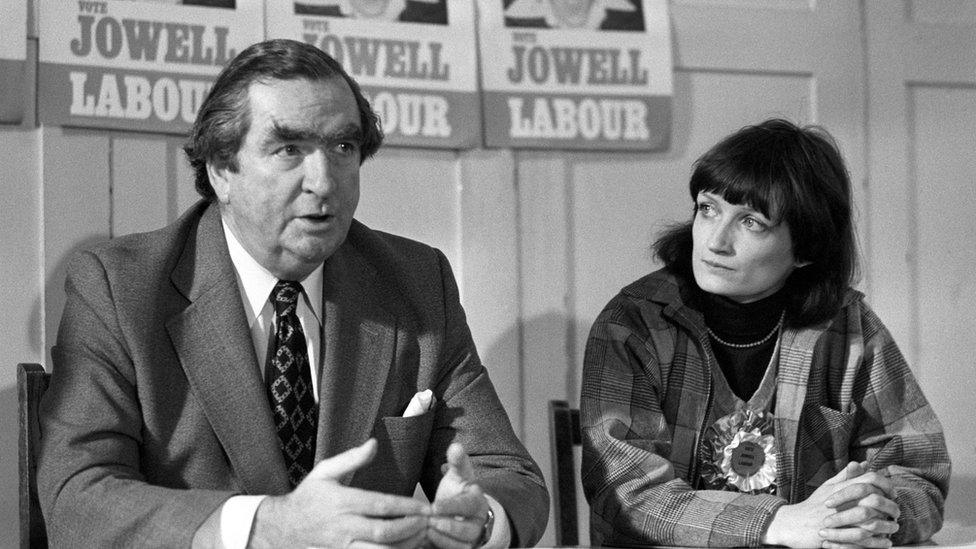

Healey (pictured here with Tessa Jowell in 1978) has been described by many as the best prime minister Labour never had

When Labour lurched to the left under Foot after that election defeat (sound familiar?), Healey narrowly defeated Tony Benn for the deputy Labour leadership by less than 1% of the vote at the 1981 Labour conference, after an acrimonious contest where one Benn acolyte was a fervent young left-winger, Jeremy Corbyn - railing against the BBC as representing the "capitalist media". That win is credited by many as turning the Bennite tide and saving Labour from utter collapse.

Despite a reputation as something of a political bruiser - he famously said "it has never been my nature to turn the other cheek" - Healey was also renowned for his wit.

Memorably he lampooned the senior Conservative minister, Sir Geoffrey Howe, for a verbal Commons assault he likened to "being savaged by a dead sheep", and later described his new parliamentary home in the House of Lords after 1992 as "the home of the living dead".

'Brave and brilliant'

Healey's reputation also obscured a more subtle and reflective side expressed through what he himself called his cultural "hinterland": a love of poetry, art, photography, and literature.

He cultivated in opposition an avuncular persona, with his trademark bushy eyebrows and colourful turn of phrase - even playing the piano for a BBC pantomime and willingly adopting the catchphrase "Silly Billy", ascribed to him by the impressionist, Mike Yarwood.

Described by many as the best prime minister Labour never had, Healey's greatest political contribution was perhaps to ensure that his party remained a credible electoral force.

In refusing to join the breakaway Social Democratic Party in 1981, and determining to "go on fighting" for the Labour Party, to which he remained ferociously loyal, Healey arguably stopped the haemorrhage of the Labour vote at a critical time.

Labour's last shadow chancellor, Ed Balls, who lost his seat in May, reacted to news of Healey death by calling him "a brave and brilliant Chancellor", while Jeremy Corbyn described the man he campaigned so hard to defeat more than 30 years ago as "a giant of the Labour Party".

- Published3 October 2015

- Published3 October 2015

- Published3 October 2015