Privy Council: Guide to its origins, powers and members

- Published

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn is the newest member - although he will not be attending its meeting on Thursday, citing a prior engagement - but what is the Privy Council and what does it do?

What are its origins?

Shakespeare dramatised meetings of the Privy Council in his history plays, including Richard II

The Privy Council dates from the court of the Norman kings, which met in private - hence the description "privy".

In those days, it was made up of those appointed by the King or Queen to advise on matters of state. In effect, privy counsellors - which included noblemen, the clergy and officers of the crown - were the chief governing body and fulfilled the role that the Cabinet performs today.

In legal terms, the Cabinet is a committee of the Privy Council.

In terms of political influence, the Council was perhaps at its most influential in Tudor times - when it had about 40 members and was used by monarchs for a variety of different purposes, both to advise on matters of war and peace and on occasions to circumvent Parliament and the courts.

There were separate Privy Councils in England and Scotland prior to the 1707 Act of Union between the two countries.

With the development of a constitutional monarchy in the 18th and 19th Century, under which the sovereign acts on the advice of ministers, the Privy Council has adapted to become an administrative link between the monarch and the government of the day with limited, formal functions.

Who sits on the Privy Council?

There are about 600 privy counsellors at the moment, including all former prime ministers and cabinet ministers as well as leaders of the opposition. Here is a full list., external

Other members include Prince Philip and Prince Charles, the current and former Speakers of the House of Commons, archbishops, senior bishops, senior courtiers, senior backbenchers and and senior judges. In practice, its regular meetings are only attended by Cabinet or very senior ministers.

MPs who are privy counsellors are referred to as right honourable members in the House of Commons.

How often does it meet?

The body convenes, on average, about once a month and its meetings - known as councils - are presided over by the Queen.

It has met six times so far this year. The last meeting was on 15 July at Buckingham Palace, external, attended by Lord President of the Council Chris Grayling, Transport Secretary Patrick McLoughlin, Leader of the House of Lords Baroness Stowell and Culture Secretary John Whittingdale.

The quorum required for each meeting, with a few exceptions, is three plus the Lord President.

The government rejects suggestions that the Privy Council is a secretive body, pointing out that details of all its meetings, attendees and the matters discussed are published in the Court Circular. Its decisions are also published on the Privy Council website.

What powers does it have?

Although it has limited powers, the Privy Council has remained an important part of the UK's constitutional architecture

The government rather dryly describes the Privy Council as "the mechanism through which interdepartmental agreement is reached on those items of government business which, for historical or other reasons, fall to ministers as Privy Counsellors rather than as departmental ministers".

In layman's terms, the Privy Council's role is to advise the monarch of the day in carrying out their duties, such as the exercise of prerogative powers and other functions assigned to them by Acts of Parliament.

Much of its business is rather routine and is concerned with obtaining the monarch's formal approval to orders which have already been discussed and approved by ministers or for the arranging for the issuing of royal proclamations.

At the meetings, the Lord President will read out the title of an order, the Queen will say "approved" and the order has the force of law. Queen Anne was the last monarch to refuse an order.

At its last meeting, for instance, the Council approved proclamations specifying the dates of bank holidays in 2016 and the design of coins commemorating the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of World War One and the Queen becoming the longest-serving monarch in British history.

Its wider responsibilities include formally approving changes to the governance of institutions, charities and companies which are incorporated by Royal Charter as well as universities and professional regulatory bodies. The Privy Council also has to officially "rubberstamp" ministerial changes, appointments to government bodies and the appointment of High Sheriffs in England and Wales.

One important area is "commencement orders", which determine when acts or sections of Acts of Parliament come into effect.

It is also the court of final appeal for the UK's overseas territories and Crown Dependencies, and for those Commonwealth countries that have retained the appeal to Her Majesty in Council, including Jamaica, Barbados, Antigua and Barbuda, Belize and Tuvalu.

What is involved in the ceremony?

New members are expected to kiss the Queen's hands after being sworn in

Jeremy Corbyn has been appointed a member of the Privy Council but has yet to be formally sworn in - which will happen at a later date.

David Cameron was not formally sworn in until three months after his election as Conservative leader in December 2005.

Mr Corbyn, who is a longstanding republican and does not believe in a hereditary monarchy, has suggested he would like to dispense with the pageantry involved, triggering speculation as to whether he would be willing to kneel before the Queen, as is traditional in the swearing-in ceremony.

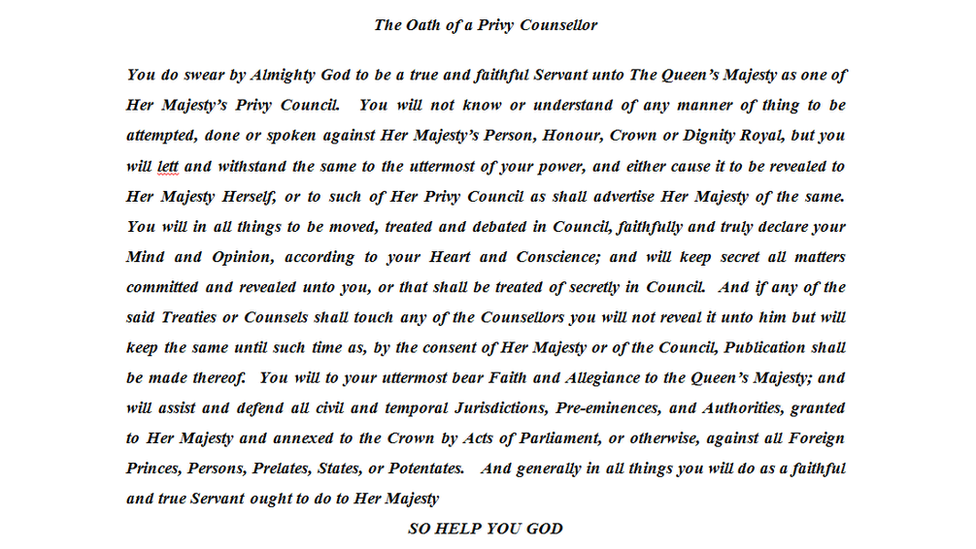

The ceremony, which is held in private, concludes with the new member kissing the hand of the Queen. Those wishing to join the Privy Council must also take a lengthy, binding oath dating back to Tudor times.

This obliges them to be a "true and faithful servant" to the Crown, to "bear faith and allegiance" to the monarch's "majesty" and to "keep secret all matters committed and revealed unto you, or that shall be treated of secretly in Council".

The Privy Council website says that "there is a solemn affirmation for those who cannot take an Oath".

It has been commonplace for prime ministers to share information, some of it classified, with leaders of the opposition on "Privy Council terms", in the express understanding that it will not be made public or divulged in any way.

This is because one section of the oath reads as follows: "You will keep secret all Matters committed unto you". And, not just merely for emphasis, the word matters commences with a capital letter.