How to punish peers?

- Published

As every viewer of the Alec Guiness comedy classic, Kind Hearts and Coronets, knows, when peers are hanged, the execution is performed with a silken cord.

After their defiance of the government on Monday, peers are waiting to see what instrument the government will devise for their punishment. And in particular they're keen to guess whether their former leader, Lord Strathclyde, will place a silken noose about their noble necks, or merely slap their noble wrists.

Conservative MPs are not amused about Monday's rebuff: "they've got to bleed," growled one senior Tory backbencher, but the options for punishment are far from simple. Despite the chuntering from sources close to ministers about "suspending" the Lords, or otherwise clipping its wings, such extreme constitutional surgery is simply not in the gift of the government. Serious constitutional reform requires passing a bill, and the investment of time and political capital necessary may simply be too great to be worth the bother.

The basic problem is that any measure to cut the powers of the Lords has to be approved by, er, the House of Lords. And should peers reject the proposals, the Government could only over-ride them through the cumbersome means of the Parliament Act. Thus the same Lords reform bill would have to be passed by MPs two years running, to become law. There is no real consensus in the Commons about how to reform the Upper House and that would become painfully clear, whatever scheme was laid before it. By immemorial convention, constitutional measures are debated in detail by a committee of the whole House, and to bring the Parliament Act into play, that process would have to be gone through twice. That means two years in which, potentially, weeks of Commons time was devoted to debating constitutional arcana.

"Oh but it can be kept manageable by timetabling the committee stage." Really? Without that elusive consensus about the shape of Lords reform, there's a good chance that, for any given reform proposal, enough Conservative MPs would oppose a timetable motion, allowing it to be defeated and tipping the government into the prospect of an open-ended committee stage, lasting for months, not weeks. It was this that caused the Coalition to abandon the Clegg Lords Reform Bill, and it could well happen again. Labour played Clegg pretty mercilessly and seem unlikely to be more sympathetic to any Conservative proposal. No Labour government has ever had a majority in the Lords, and their MPs think the government should suck these defeats up, just as Tony Blair and his predecessors had to. And let's not even think about the consequences for government legislation if peers were really riled.

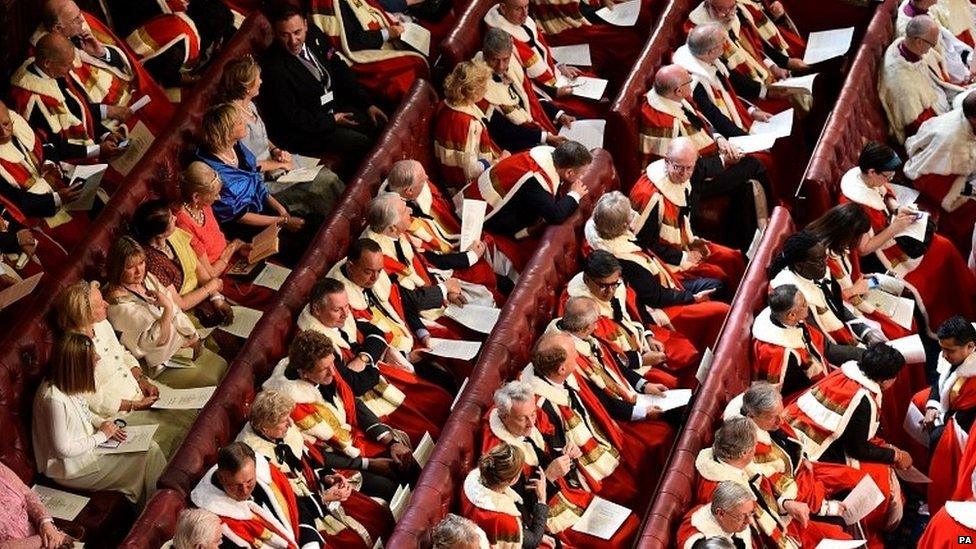

So, if a Lords reform bill of some kind is a politically expensive and difficult exercise, what about creating a new wave of Tory peers to swamp the opposition parties? That would mean more than a hundred. Again, that is difficult, for different reasons. For a start the government has created a lot of new Tory peers already, new noble Lords are being introduced to the House at the rate of four or so a week, there are four more due next week. And it's not a done deal that the Queen would simply create as many peers as the prime minister wanted, even if the Crown is not quite as independent as it was the last time that option was proposed by a prime minister.

That was Asquith's call, a hundred years ago, for a mass creation to overwhelm Tory peers who were blocking his Liberal government's legislation. The monarch, first Edward VII, then George V, insisted that he should seek a mandate from a general election first. Thanks to the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, that course is not available to David Cameron. But a semi-precedent remains for the monarch to require more than a simple request before tilting the political balance of a house of parliament. And that's before we get to the politics of a mass ennoblement to enable tax credit cuts to working families, which would be a pretty hard sell.

So what are we left with; Lord Strathclyde seems to have a pretty minimalist mandate to find a way of extending the Commons "financial privilege" to cover statutory instruments like the ones which would have implemented the tax credit cuts. But it is sinking in, at the Lordly end of Westminster that it could have a big effect on their scrutiny of the Government.

SIs, or secondary legislation, are regulations made under the terms of Acts of Parliament. They're supposed to allow ministers to tweak the operation of the law without having to push a full dress bill through. And the reason the tax credit cuts were attempted through an SI was that the original 2002 legislation that created the system specified that SIs should be used to alter the rates at which they were paid, and that they should go through both Commons and Lords. One worry about them is the trend towards skeleton bills that simply give the power for ministers to make sweeping regulations on big policy questions. These seldom get much scrutiny in the Commons, which normally waves them through. And in any event they are unamendable, at the moment peers can accept or reject them, and the only other option is to pass a "regret motion," which signals their displeasure but has no other impact. What they can't do is make changes which would remedy any defects they spot.

And that brings us to the nub of the complaint about making the tax credit cuts by SI: it's a huge policy change made through a one-off vote in each House. No amendments and not much debate. Skeleton bills are rarer than they used to be, but there are still a handful each year and that's one of the big reasons why more SIs are being rejected or, at least, regretted in the Lords.

Some voices in the Lords think that if the government wants to enact major financial decisions by SI, the Lords should accept that the elected House is in charge of the money. Others say that this trend is a way of avoiding troublesome scrutiny and should be resisted. And because so many SIs have financial implications, they fear that the end result of extending financial privilege could be a sharp cut in parliamentary scrutiny.

And what about the longer term? A working group of peers under the Conservative constitutional scholar, Lord Norton of Louth, is attempting to devise consensus proposals that both reduce the size of the House to something comparable to the Commons, a reduction by about a third and to bring the political membership a little more closely into line with the most recent election result (while keeping 20 per cent of the Lords as non-party Crossbenchers). In practice that means fewer Lib Dems, and maybe more UKIP peers depending on whether a formula is agreed which reflects election votes or Commons seats. (The SNP would be offered Lords seats, but their current policy is that they don't accept them).