Labour's week: Fear and loathing in SW1

- Published

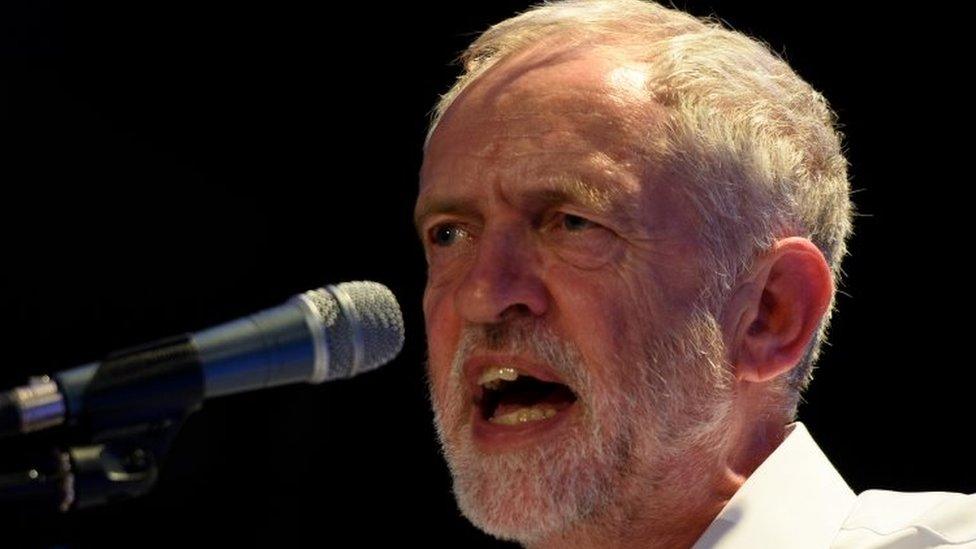

The Labour Party has had a torrid week with leader Jeremy Corbyn at odds with his MPs over defence policy and a row over Ken Livingstone's comments about a shadow minister.

At the core of this week's difficulties for Labour is a clash of mandates.

Until that tension is resolved - one way or another - the symptoms are likely to present themselves as splits.

Jeremy Corbyn has the largest mandate of any Labour leader from party members and supporters.

He also has the shallowest support from Parliamentary colleagues of any of his predecessors.

The 90% plus of Labour MPs who didn't vote for him would argue that they draw their mandate from a far wider section of the population: the people who elected them in May.

And some would argue that the MPs draw their legitimacy from a manifesto which committed Labour to balancing the books and a continuous at-sea nuclear deterrent - policies to which the current leader doesn't subscribe.

Livingstone row

There is a feeling at Westminster that the phase of phoney war between the leadership and most MPs is beginning to turn in to an actual conflict.

It's not all out war, by any means but the skirmishes have begun.

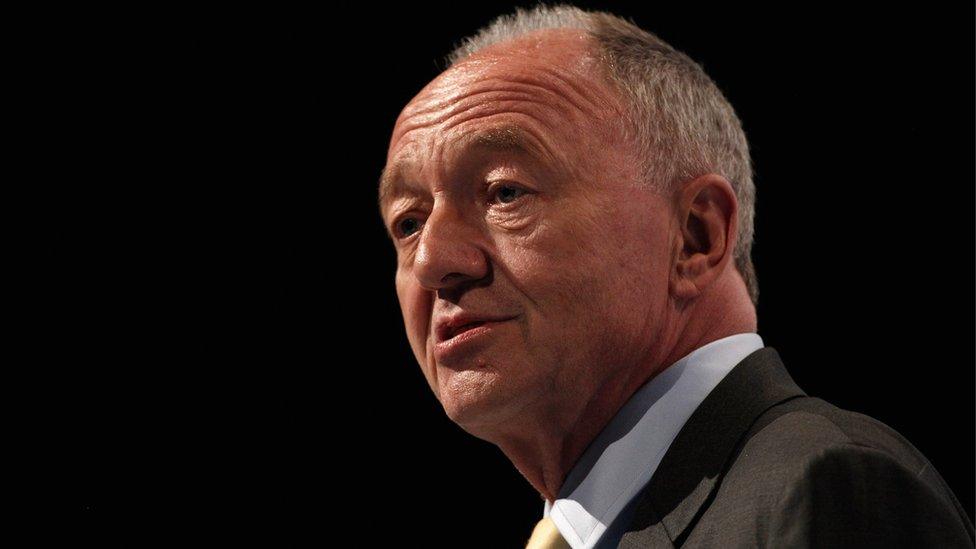

Ken Livingstone has apologised for the comments directed at Kevan Jones

The pre-emptive strike came from the Corbyn camp when Ken Livingstone, who supports unilateral nuclear disarmament, was imposed on multilateralist Maria Eagle, the shadow defence secretary, to co-chair her review of where the party stands on renewing Trident.

Shadow defence minister Kevan Jones - who was close to Gordon Brown - retaliated, questioning Livingstone's suitability for the role, and for his trouble was told by the former London mayor to seek psychiatric help.

Jones is known to have suffered from depression in the past.

Livingstone was later required to apologise and claimed he had no knowledge of Jones's medical history.

Red rag

The reason, though, that relations are reaching a nadir is that there appears to be little appetite for compromise on both sides.

The appointment of Ken Livingstone wasn't done as a result of widespread consultation. Quite the reverse. It was a deep red rag to an increasingly bullish Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP).

Eagle saw Livingstone appointment on social media

MPs had just elected - or in some cases, simply selected - largely a coterie of Corbyn critics to chair their parliamentary party's departmental committees, which monitor the work of shadow ministers.

And the chair of the defence committee John Woodcock - who also represents the constituency in which the nuclear submarines are built - used his new position to write to Maria Eagle asking about the process behind Livingstone's appointment and whether she herself had been told. The letter found its way in to the public domain.

What in turn is fuelling the lack of compromise is - for want of a better phrase - a degree of fear and loathing on both sides.

Those around Jeremy Corbyn would argue that when Labour MPs recognise his mandate the Conservatives can be put on the back foot.

Rail re-nationalisation

The talk over the summer, under interim leader Harriet Harman, of perhaps accepting some Conservative changes to tax credits has been ditched, and it is George Osborne who is on the back foot and having to find a compromise imposed upon him by the Lords - largely as the result of Labour's tactics in the Upper House.

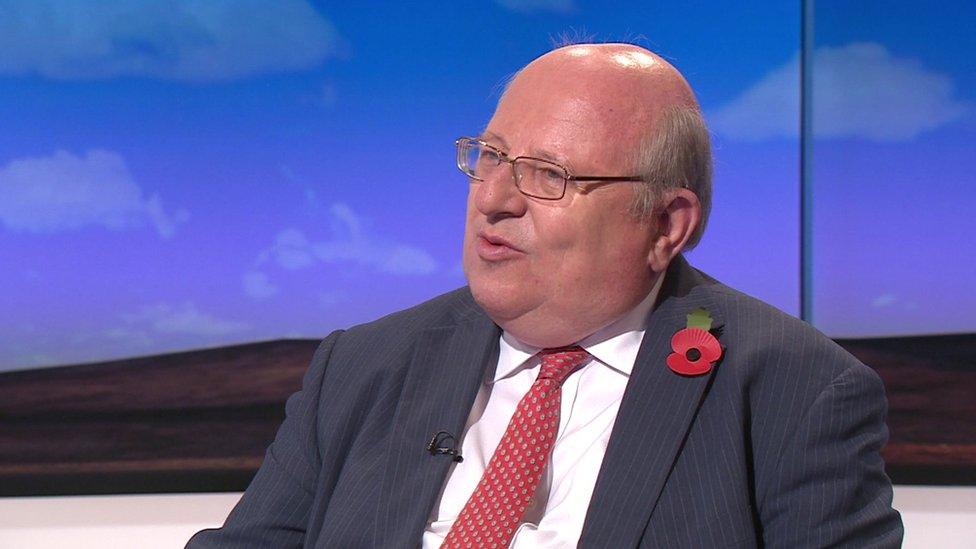

Mike Gapes has previously suggested the party has no "credible leadership"

Corbyn's policy of rail re-nationalisation isn't proving unpopular, either, and the party demonstrated unity around the proposal to bring the railways into public ownership incrementally.

And he would claim credit for putting pressure on the government to cancel a contract with Saudi Arabia's prisons - uniting his party around human rights concerns.

The vision - at least in the short term - was that a mixture of the leader's patronage and the unspoken but understood threat of deselecting MPs who are out of touch with the more radical membership would mean that many of the Parliamentary party would accept a move to the left and the eventual close alignment of leader and policy. Therefore, there would be no need for a political civil war.

But some of those close to Corbyn are frustrated that too many of his MPs are willing to undermine him publicly and, they suspect, these MPs are actually attempting to destabilise his leadership.

There was bitterness at the suspension from the party of Corbyn's policy adviser Andrew Fisher for apparently advocating support for a party other than Labour - in this case, Class War - following complaints by MPs opposed to Corbyn.

Syria vote

In turn, Corbyn stuck two fingers on presumably his left hand up to party apparatchiks and retained Fisher in his private office.

A senior Labour figure who didn't back Corbyn - but was willing to compromise with him and serve under him - privately described his actions over Fisher as a declaration of war on his own party.

So the tone has become less emollient.

Corbyn hasn't committed to giving his MPs a free vote if there is a proposal from the prime minister to extend air strikes to Syria.

In opposing air strikes, Corbyn knows, should any showdown come, he is bolstering his own backing amongst grassroots members of his party who joined to support him.

Now that, in turn, is spooking some of his MPs.

And that understated threat of deselection became a bit more explicit when Ken Livingstone told the BBC's Sunday Politics programme 'If your local MP is undermining Jeremy Corbyn, people should have a right to say 'I'd like to have an MP who reflects my views'. It shouldn't be a job for life."

By-election fears

The existence of the pressure group Momentum, which describes itself as "a network of people and organisations that will continue the energy and enthusiasm of Jeremy's (leadership) campaign", is also seen by some MPs as a potential vehicle designed to run them out of Parliament.

So some Labour politicians believe they may as well speak out as they have little to lose.

Frank Field has already raised the prospects of resignations to force by-elections in which Corbyn's candidates - if the polls are to be believed - could lose.

And talking of elections, the prospect of doing badly in them is also concentrating minds at Westminster.

Spencer Livermore said Labour was going backwards under Corbyn

There will be a by-election early next month in Oldham and insiders say canvass returns are suggesting the party's support has slipped back since the general election.

The man at the centre of that campaign - Spencer, soon to be Lord, Livermore told the World At One that all the fundamental problems which led to Labour losing in May are still in place and getting worse - the party is still behind in the polls on the question of leadership, and on the economy.

And Livermore believes the policy offer and vision is still too narrow to appeal to a majority of voters.

He is encouraging colleagues to speak out, saying: "People are right to be critical that we are heading in the wrong direction."

Against this backdrop, some MPs feel they may as well say what they think.

Shoot-to-kill

What worries a section of them isn't so much the leftwards drift of the party but a perceived lack of competence.

In his BBC interview on Monday, it was felt that Corbyn walked into a trap on questions about his attitude to "shoot-to-kill" in the face of terrorist threats.

He said: "I'm not happy with the shoot-to-kill policy in general - I think that is quite dangerous and I think can often can be counter-productive."

He had to clarify his position on Facebook, and to his own National Executive Committee, saying he was in favour of "proportionate force".

A leader with the goodwill of colleagues would have had his MPs rally round him.

Instead, every bit as much as the Conservatives, some of Corbyn's own colleagues pounced on his remarks.

Ian Austin, a former Brown aide who now chairs the PLP's education committee, and the Blairite Mike Gapes - who is now at the helm of the PLP's foreign affairs committee - explicitly agreed with the prime minister's position in the Commons chamber on Tuesday while offering veiled criticism of their own leader.

Inevitable conflict?

There are no signs, as yet, of an actual plot to get rid of a recently elected leader - more a worry and a frustration that he sounds too out of tune with the concerns of voters that Labour needs to win back.

Ousting him in any case is tricky.

It's not clear even if the required 20% of MPs ask for a contest that they would succeed in dislodging him.

Party rules are likely to be clarified to state that, as the existing leader, he would automatically be on the ballot.

So if the new party members like his radicalism and feel he is under attack from a Westminster establishment he could be re-elected.

Even though both sides know that continued tensions are damaging and not easily resolved, the momentum points towards their being ratcheted up.

The initial period of near peaceful co-existence between a leader and a parliamentary party that doesn't want him is ending.

Greater conflict seems inevitable but which side will triumph -or even if there will be anything like a decisive victory and a new settlement - isn't clear.

- Published19 November 2015

- Published18 November 2015

- Published6 November 2015

- Published6 November 2015

- Published18 November 2015