Deselection fear hangs over Corbyn's critics

- Published

Jeremy Corbyn has attracted new supporters to the Labour party

"Cut out the personal abuse," Jeremy Corbyn told the Labour Party conference in September. As with so many of the leader's pronouncements, this is being honoured by some of his supporters more in the breach.

So bad have things got that the NEC, Labour's ruling body, is to draw up social media guidelines to discourage abusive posts.

Quite how they can be enforced, though, when so many conceal their identities online isn't clear.

Some of the most vicious language has been deployed against Labour MPs who have been critical of the leadership.

On Twitter, swearing aside, they've been accused of being "red Tories".

Ann Coffey, who has represented Stockport since 1992 was told: "Get behind the leader or kindly go.", external

In response, she said she will "await the assassins to come out of the shadows".

Assassins? What Ann Coffey is referring to is the great fear now stalking the Parliamentary Labour Party - deselection.

The thousands of new members flooding constituency labour parties (CLPs) were enthused by Mr Corbyn's leadership campaign.

Ann Coffey has attracted online criticism

Most will find themselves with an MP who does not share their enthusiasm. So are we about to see a return to the Labour Party fratricide of the early 1980s?

At the start of that decade, Labour introduced a new rule requiring sitting Labour MPs to face a constituency vote once in every parliament to determine whether they should be the candidate at the subsequent general election.

Victory for left

It was a significant victory for the left, after years of work by the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy (CLPD).

There had been reselection battles before, most recently in Newham in east London in 1976 where Reg Prentice, external, a cabinet minister, was dislodged by what he claimed at the time were infiltrators.

The cause of those who shared his fear of entrysim was not helped when Prentice subsequently defected to the Conservatives.

There is no doubt that mandatory reselection helped to destabilise local parties.

When I spoke to Chris Mullin, who was active in the CLPD and later served as a minister in Tony Blair's government, he used a phrase that resonates today - that some MPs had drifted apart from their local parties.

Yet he argues that almost none of the deselections that followed were ideological.

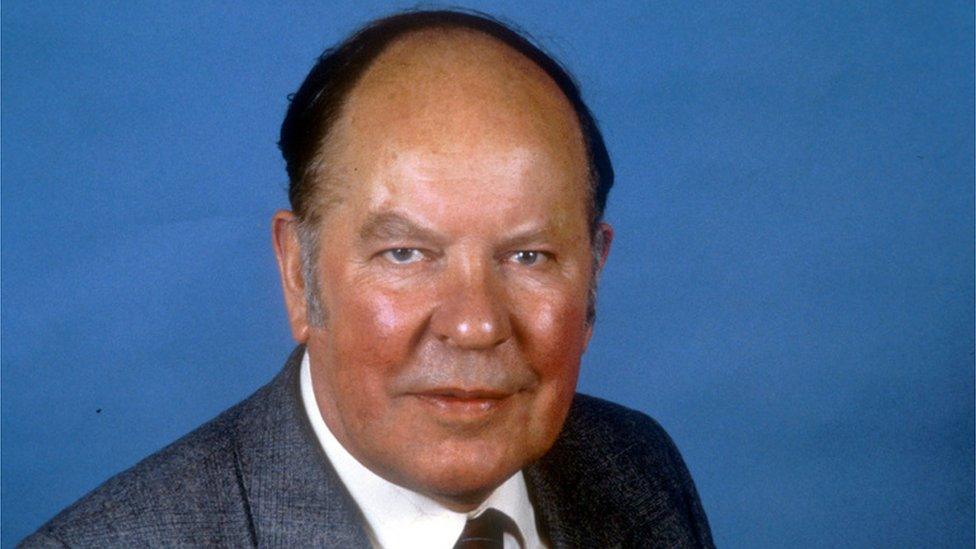

Reg Prentice was deselected by his local Labour party in 1976

Mr Mullin argues that what mandatory reselection did was allow local activists a say, while ending the political freehold that sitting MPs in safe seats had enjoyed.

As proof, he points to Vauxhall in south London, where he was a party member in the late 1970s.

The MP was George Strauss, who was fast approaching his half century representing the area.

"It was a dreadful state of affairs," Mr Mullin recalls.

Strauss first stood in 1924, losing only narrowly, winning the seat in 1929, losing it in 1931 but winning it "for good" in 1934.

By then in his late 70s, he fully intended to carry on.

His power over the local party included owning its offices (which, he made clear, the CLP would lose if he was deselected) and using his personal secretary to run the local party.

"MPs would tend to stay on one parliament too many, or in some cases two or three," Mr Mullin says.

Complacency had set in, with CLPs in safe Labour constituencies becoming largely moribund.

By 1980, when the rule change was introduced, George Strauss had retired, taking the keys to the constituency office with him; perhaps he'd seen the writing on the wall.

Yet there were still plenty of Labour MPs who had been knocking around since the war; some, including John Parker in Dagenham, had been there since the 1930s.

Was it a purge?

Between 1979 and 1983, when the influence of the left was at its peak, that number fell.

How far it can be described as a purge, though, is questionable.

Mr Mullin argues that only one of the deselections that preceded the 1983 general election was ideological, that of Frank Hooley by the Sheffield Heeley CLP in 1983.

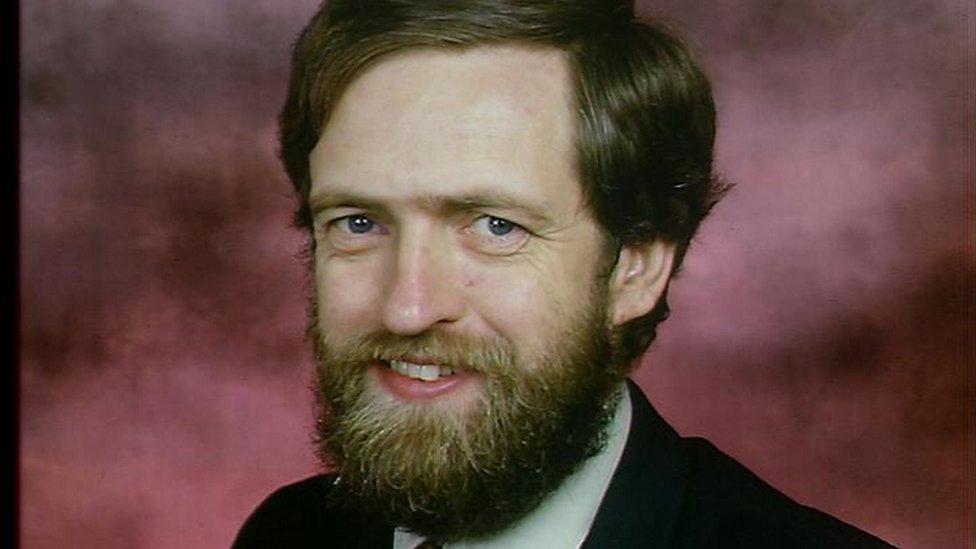

Former Labour leader Neil Kinnock introduced restrictions on reselection

More typical was the dismissal of Frank Tomney in Hammersmith North.

The "crusty, old, far right" Mr Tomney - as the Guardian described him - was replaced by Clive Soley, a local councillor, to the left of Tomney certainly, but in Labour Party terms pretty mainstream.

It may be that many MPs jumped first, fearing they would be pushed.

Certainly, the reselection threat may be one of the factors that led Labour MPs to defect to the SDP.

Mandatory reselection has been identified as one of the rules scrapped by Neil Kinnock as he dragged Labour towards the political centre.

In fact, it was restricted rather than removed. For an MP to be forced to fight for the party nomination in his or her constituency these days, there has to be a trigger ballot by the CLP.

Even then, the incumbent is guaranteed a place on the final shortlist.

Labour party rules on reselection:

If the sitting MP wishes to stand for re-election, a trigger ballot will be carried out through party units and affiliates according to NEC guidelines.

If the MP wins the trigger ballot he/she will, subject to NEC endorsement, be selected as the CLP's prospective parliamentary candidate.

If the MP fails to win the trigger ballot, he/she shall be eligible for nomination for selection as the prospective parliamentary candidate, and he/she shall be included in the shortlist of candidates from whom the selection shall be made.

If the said MP is not selected as the prospective parliamentary candidate he/she shall have the right of appeal to the NEC.

Boundary changes

Momentum, the ginger group made up of those who've been nicknamed Corbynistas, insists it is not organising deselections, though some of its senior figures are veterans of those days.

The "kindly go" tweet aimed at Ann Coffey originated from a member of Momentum - but was swiftly taken down and its message disowned.

In October, Jeremy Corbyn offered these words of reassurance, external to his backbench critics: "I wish to make it absolutely crystal clear that I do not support any changes to Labour's rules to make it easier to deselect sitting Labour MPs."

There's another factor, though, which applied in the 1979 parliament and will do so again, and which makes Mr Corbyn's words less reassuring. Boundary changes are in the offing.

The Conservatives want constituencies which have more or less the same number of voters as each other, and that would reduce the number of inner city seats, most of them Labour.

Jeremy Corbyn won his Islington seat following boundary changes before the 1983 general election

They also want to cut the size of the Commons to 600.

Changed boundaries will force reselection battles up and down the country, and as all those twitter exchanges suggest, it could get nasty.

Jeremy Corbyn may not be planning to change the rules, but in these circumstances only the National Executive Committee (NEC) stands in the way.

It will determine whether the new boundaries are so different from the old ones that an open contest should take place.

If the Boundary Commission does propose constituencies with equal numbers of voters, dozens of sitting MPs would be likely to have to face up to a selection battle.

Ahead of the 1983 election, although the commissioners were given greater discretion than they will have this time, 90% of constituencies had their boundaries changed.

Two of them were in Islington in London, where reducing the number of seats from three to two allowed the CLPs to ditch both sitting MPs: John Grant fought the revised Islington North for the SDP, winning 22% of the vote; Michael O'Halloran, running as an independent, polled just 11%.

Who topped the poll? A then obscure young party activist, one Jeremy Corbyn.

General Election 1983: Islington North:

Labour: Jeremy Corbyn 14,951 (40.4%)

Conservative: David Coleman 9,344(25.3%)

Social Democratic: John Grant 8,268(22.4%)

Independent Labour: Michael O'Halloran 4,091 (11.1%)

BNP: LAD Bearsford-Walker 176 (0.5%)

Independent: Roy Lincoln 134 (0.4%)

I wouldn't yet put my money on a parliamentary bloodbath this time, but don't be surprised if a significant number of Labour MPs opt to retire before the next general election.

It will give activists what they want without blood being spilt.