Is political impressionism doomed?

- Published

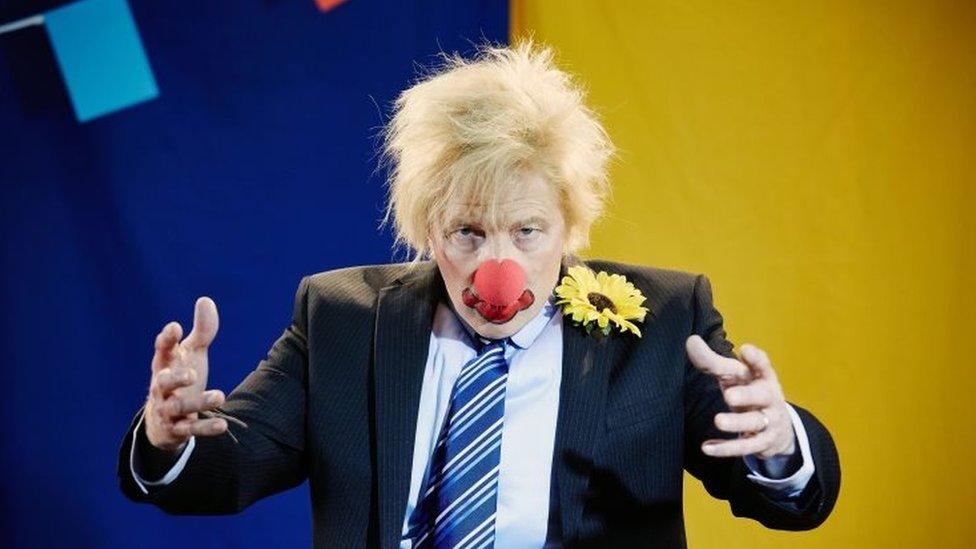

Rory Bremner as Boris Johnson

Politicians were not the only ones in shock when the general election exit poll came out, it was also a rude awakening for Britain's impressionists.

Many favourites were simply wiped away: Ed Miliband, Nick Clegg, even Eric Pickles. Was Boris Johnson their only consolation?

It was no better for female impersonators: while Nicola Sturgeon was a welcome new voice, the grim reality dawned: it would no longer be possible to put off doing Theresa May.

"My life flashed before me and Miliband wasn't in it," Rory Bremner told BBC Radio 4's The Westminster Hour.

"I lost Galloway, which was a tragedy for impersonators everywhere," says Lewis Macleod, of Dead Ringers.

Pondering his other losses that night, he jokes: "I suffered a heavy defeat and I didn't even get a severance package."

Politicians do not owe impressionists a living, of course, but their art has become such an established feature of British politics that it would be a shame if a dearth of strong characters on the green Commons benches was to kill it off.

'Stupid great grin'

It all began with Peter Cook in Beyond the Fringe. His befuddled take on Harold Macmillan, the patrician grouse moor Tory who told Britons they had "never had it so good", was seen as a thrilling challenge to the old, established order at the birth of the "satire boom" in the early 1960s. No one had dared to impersonate the prime minister before.

Much to Cook's annoyance, Macmillan sat in the stalls one evening chortling away as his own mannerisms and voice were mercilessly sent-up, prompting the satirist to depart from his script, saying, in Macmillan's pompous tones: "There's nothing I like better than to wander over to a theatre and sit there listening to a group of sappy, urgent, vibrant young satirists with a stupid great grin spread all over my silly face".

Peter Cook (second left) pioneered the art of the political impression in the early 1960s

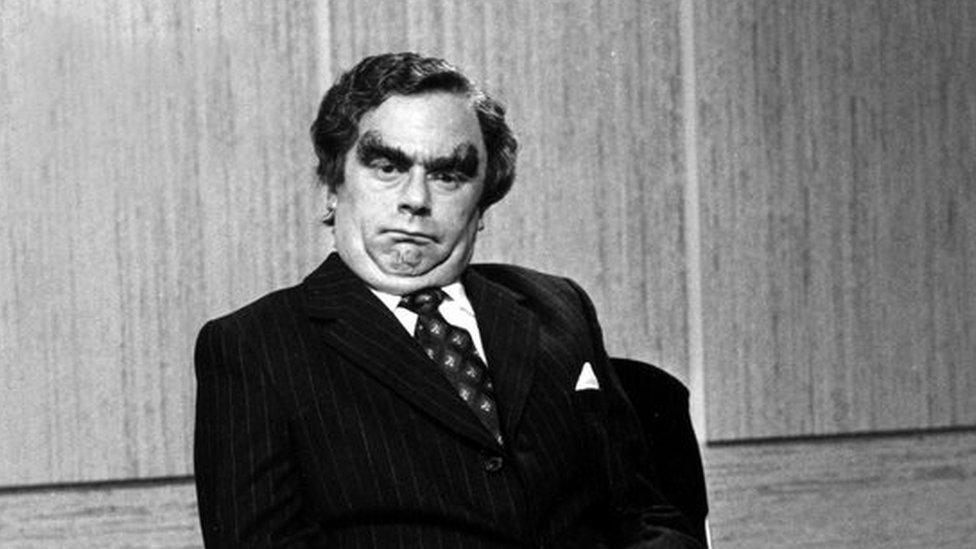

Mike Yarwood, here doing his Denis Healey, took it to a mainstream audience

Political leaders like Harold Wilson appeared on Yarwood's programmes

History does not record whether this wiped the grin off Macmillan's face. But if Cook thought his barbs would stop politicians trying to get in on the joke, he had underestimated the thickness of their hide or their seemingly pathological desire to be seen as a good sport.

Sitting with a silly grin on your face, on a chat show sofa, as a comedian mimics your strange mannerisms is now a rite of passage for Britain's political leaders.

Golden age

It was Mike Yarwood, with his affectionate but deadly accurate take-offs of characters like Ted Heath, with his heaving shoulders and toothy grin, and Denis Healey, all bushy eyebrows and bluff bonhomie, who brought political impressions to a mainstream television audience. He even furnished Healey with a catchphrase - "silly Billy" - which became associated with him in real life.

Yarwood also pioneered the trend for impersonating political journalists - who were (and still are) just as eccentric, or larger than life, as those they interrogate - with his wheezy take on the obstreperous Sir Robin Day.

Rory Bremner has perfected his Nick Robinson

And his Robert Peston

Rory Bremner took up Yarwood's mantle in the 1990s, although his act owed more to the golden age of political satire than light entertainment. He even recruited two stalwarts of the 1960s scene, John Bird and John Fortune, to add extra bite to his send-ups of Tony Blair's government and the perceived inanity and spin of New Labour.

The one thing all of these impersonators have in common is that they had great material to work with.

The need to look good on television has steadily worn the rough edges off our political leaders. It is not media training - Gordon Brown had plenty of that, but was still a rich seam of vocal and facial tics for the nation's impressionists, more a by-product of the managerialism that has infected the upper reaches of public life.

The tide may be turning, however.

The public's rejection of smooth, identikit politicians - witness the rise of Jeremy Corbyn, Nigel Farage and Donald Trump - could yet herald a new golden age for impressionists.

"When Clinton was the president I think he had been impeached before I had mastered his voice," says Lewis Macleod, who has got in early with a Trump impersonation.

His Dead Ringers colleague Jan Ravens tells the Westminster Hour she is working on her Hilary Clinton, with her folksy, "down home" tones and attempts to come across as a regular "gramma".

Rory Bremner says his Jeremy Corbyn is a work in progress - his starting point is the ineffectual, well-meaning warder Barraclough, in classic prison sitcom Porridge.

But the veteran impressionist has developed a fondness for impersonating David Cameron, despite the prime minister's lack of any obvious vocal eccentricities.

And if all fails there is always Boris, or the political broadcasters, to fall back on.